Research data repositories play a vital role in ensuring research is reproducible, replicable and reusable. Yet, the infrastructure supporting them can be impermanent. Drawing on a new dataset Dorothea Strecker, Heinz Pampel, Rouven Schabinger and Nina Leonie Weisweiler, explore how common data repository shutdowns are and suggest what can be done to ensure data preservation in the long-term.

Research data repositories, such as Zenodo or the UK Data Archive, are specialised information infrastructures that focus on the curation and dissemination of research data. One of repositories’ main tasks is maintaining their collections long-term, see for example the TRUST Principles, or the requirements of the certification organization CoreTrustSeal. Long-term preservation is also a prerequisite for several data practices that are getting increasing attention, such as data reuse and data citation.

For data to remain usable, the infrastructures that host them also have to be kept operational. However, the long-term operation of research data repositories is challenging, and sometimes, for varying reasons and despite best efforts, they are shut down. We know from previous research that repository shutdown is to be anticipated, but research is currently limited to specific disciplines and repository types.

Investigating repository shutdown

In a recent study we therefore set out to take an infrastructure perspective on the long-term preservation of research data by investigating repositories across disciplines and types that were shut down. We also tried to estimate the impact of repository shutdown on data availability.

To get a broader perspective on repository shutdown, we based the sampling on the registry re3data. re3data is currently the most comprehensive source of information on research data repositories, with more than 3000 records. We reviewed each repository the registry considered closed, and after applying our inclusion criteria, we identified 191 repositories that were shut down. To collect information on the shutdown process, we analysed repository websites, both the current version and versions archived by the Internet Archive, as well as additional resources such as data papers describing the repositories. The resulting dataset is published and free to reuse.

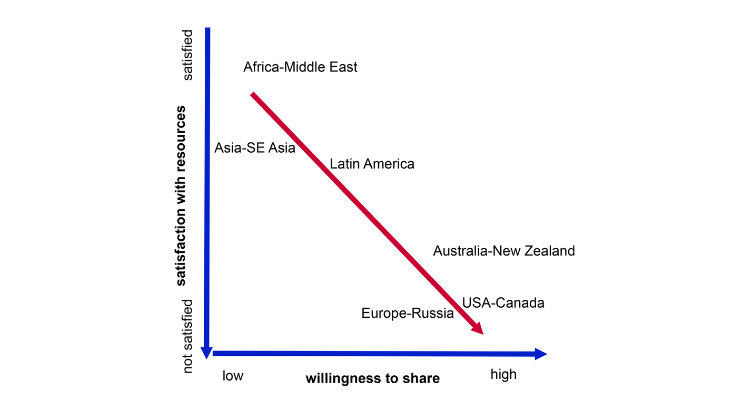

We found that repository shutdown was not rare: 6.2% of all repositories listed in re3data were shut down. Since the launch of the registry in 2012, at least one repository has been shut down each year (see Fig.1). The median age of a repository when shutting down was 12 years.

Fig.1: Number of closed repositories indexed in re3data per year (cumulative)

For the majority of repositories in the sample (120), the reason for shutting down remained unknown. For the others, known risks resulting in shutdown were organisational failure (37), economic failure (27), hardware / software obsolescence (5), external attacks (2), and media obsolescence (1).

We also looked at two strategies repositories can employ to prevent data loss: Maintaining limited access to data (for example via a simple FTP interface), and data migration (transferring data custody to another repository). The results showed that 12% of the repositories in the sample maintained limited access to data, and 44% migrated data before shutting down. 47.1% of the repositories did not indicate using either strategy, which means that there is a high risk of permanent data loss after shutdown.

Managing the risk of shutdown

Repository shutdown is not uncommon and should be planned for in advance. However, planning for the long-term preservation of research data is challenging, because various factors can put both the data and the repository that holds them at risk. Only little more than half of the research data repositories in the sample have detailed strategies they use to mitigate data loss. It is important to note that none of the strategies analysed offers a permanent solution; instead, infrastructure maintenance requires continuous efforts. The burden of infrastructure maintenance and data preservation is currently placed on individual repositories alone; preservation systems comparable to those for scholarly texts, such as CLOCKSS, are not widely spread and can be difficult to realise. Collaboration of repositories in this area could contribute to reducing the risk of permanent data loss.

Overall, the study revealed a lack of information on repository shutdown processes. This issue could be addressed by registries, which are uniquely positioned to provide more detailed information on the shutdown process, or database transition pages, which point potential data reusers to new sites of storage after data migration.

The findings demonstrate that repository shutdown does happen and can result in permanent data loss. Broader discussions in the scholarly community are needed to determine the gravity of this issue. Data reuse and citation are increasingly promoted by journals, funders and other stakeholders. If these practices become more common, data loss might pose a threat to the permanence of the scholarly record. However, it remains to be seen how the application of these practices evolves, and if datasets that have been lost permanently were cited. More research is needed, but we hope our paper adds to these much needed discussions.

This post draws on the authors’ article, Disappearing repositories: Taking an infrastructure perspective on the long-term availability of research data, published in Quantitative Science Studies.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: ariadna de raadt on Shutterstock.

A fraction of APC charged by journals to authors (or institutions) is supposedly intended to support long-term preservation and access to publications and data files. However, although no one knows the future, the most likely scenario is that everything will be gone 100,000 years from now, including our civilization and ourselves. For the medium term, perhaps an archaeology of the 21st century Science will develop, with researchers attempting to read damaged hard drives and decipher some esoteric python codes, scratching their heads…

Physical archives have a culture of ensuring they find a home for content on shut down, and I’d assumed this was shared by data repositories. But it seems not. With our growing appreciation of the importance of open research, and the potential of collections as data, it seems a real shame that these digital archives should make it this far and no further.