Joachim Roth, sustainability analyst and department alum, investigates the geopolitics of the inevitable global energy transition.

With the prospect of the energy transition looming, there is a need to analyze what the geopolitical implications of such a shift could be. Although there is no universal definition of what geopolitics stands for it can be interpreted in relation to the energy transition as the way nations can influence each other through energy supply and demand. This is how the geopolitics of energy has functioned since the advent of the industrial revolution. States that possess cheap and abundant energy, such as oil in the case of the OPEC countries, can control its production and yield influence over other nations. To a certain extent, due to the inertia of the current energy system which is still largely based on oil and gas, such a theory still holds true. We can see this in the sheikhs versus shale standoff where through increased fracking American oil production increased and was able to reduce its dependence on Saudi-oil imports. There are abundant other examples including Ukraine destroying its power transmission lines to Crimea during the conflict between Russia and Ukraine or even President Putin using different gas pricing methods across Europe to fragment its unity. Is this form of conflict over who controls access to energy likely to change in the coming decades?

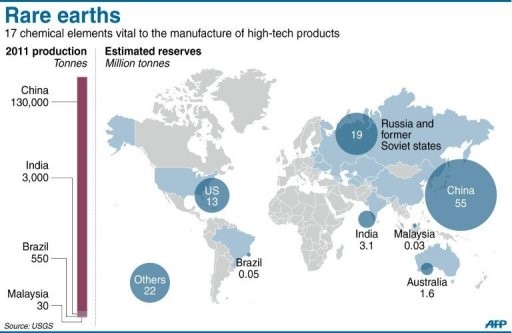

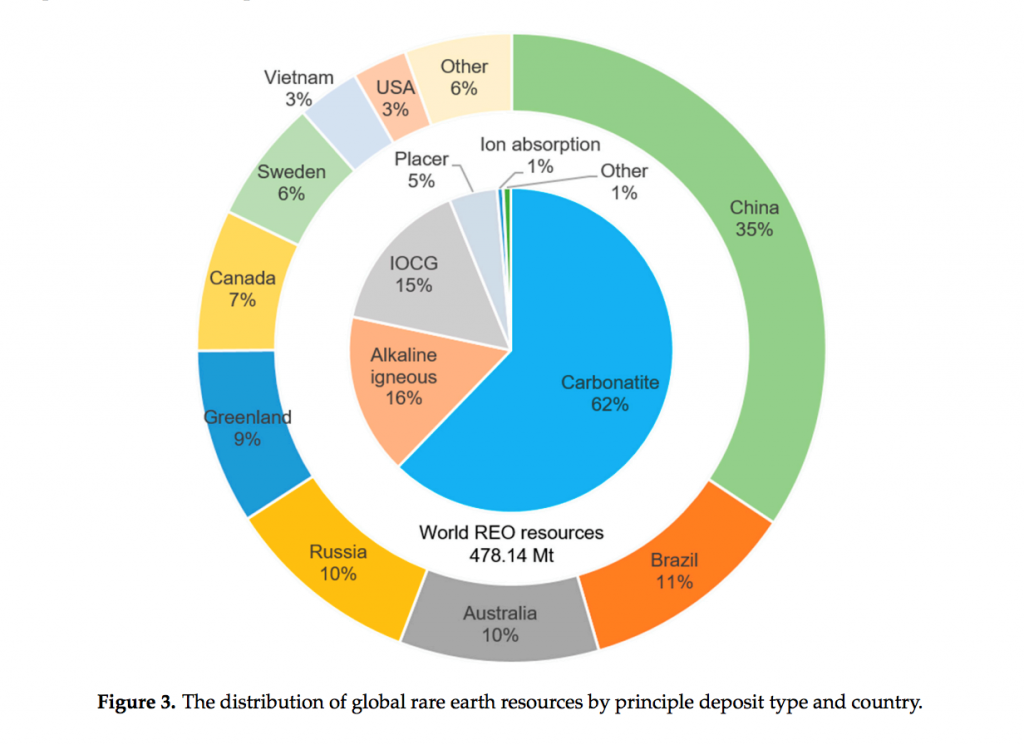

If we examine the sourcing of raw materials needed to produce solar panels, wind turbines and even electric vehicles then the answer is no. Renewable technology uses a variety of minerals such as lithium iron, nickel and cobalt from countries such as Chile or the Democratic Republic of Congo and rare earth materials of which 80% of the production is from China. The sourcing of these materials is problematic from a geopolitical standpoint. It creates a global dependency for these resources that is based only a select number of countries, despite the fact that renewable endowments for wind, solar, geothermal and biomass are scattered geographically. Controlling the production of these new commodities will have major geopolitical consequences, not only for energy transition, but also in the realm of modern defense and communications technologies. All nations should strive to increase their investments in these emerging commodities, in order to diversify global production away from Chinese domination. Another important component will be reducing instability in regions rich with these resources, such as Central Africa and the East Indies, to ensure reliable access to the next generation of energy resources.

This sourcing dependency is a cause of concern, particularly in China, which grants access to its market and cheap labor, in exchange for technology transfer from major car manufacturers such as Tesla or Nissan. In 2016, the US even filed a WTO complaint against China for disadvantaging its domestic car producers. The same trend is occurring when examining the green race to deploy renewables such as solar or wind. The number of WTO related complaints have surged, possibly jeopardizing in the long run the global development of renewables. The development of renewables is also worrying as mining for components such as batteries can lead to highly polluting activities with high environmental costs for local communities. In order to meet the emission reduction targets set during the Paris Agreement, mining activities need to be more tightly regulated and manufacturers need to abide by responsible sourcing practices. Without taking into account these dimensions, the geopolitics of energy are likely to remain the same, only this time benefitting new actors such as China.

Yet, there is a solution which could change the rules of the game. This could happen if we move from a globally centralized to a decentralized energy model. The energy transition has the potential to usher in a societal change whereby renewables are not simply deployed at the state or central level as was the case with conventional fossil fuels but at the sub-national, regional and local level. In that sense the energy transition can be more decentralized with mini-grids, off-grid technologies, smart grids, solar rooftop panels and remote wind turbines all having the potential of distributing electricity and generating revenue streams that are directly controlled by local people. This has immense potential to generate economic growth in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa where until 2017 only 37.5% of the population had access to electricity. Decentralization can also have a democratization effect as has been the case with Germany’s Energiewende where local communities become full actors in the diffusion of renewable technologies. Berlin’s “Energy Table Movement” was instrumental in tackling fuel poverty and energy democracy for example by creating an alliance with society groups for citizens to be self-sufficient in their energy needs and not dependent on private providers . Yet, how these two forces, the decentralization of the grid and the sourcing of commodities will in the long run affect the geopolitics of renewables is still uncertain.

As oil and gas remain the dominant sources of energy until at least 2030, it is likely the geopolitics of renewables will coexist with those of conventional fuels. It is also important to note that without improvements in storage and transmission technology, renewables will remain a marginal share of the energy mix. It appears that for the foreseeable future, without a rethinking of the current energy paradigm, old energy politics are back on the table, albeit with new actors such as China better poised to exploit them.

Joachim Roth holds a master’s degree in development studies from the London School of Economics and Political Science. At the time of writing he worked as a sustainability analyst at the Centre for Development and Strategy, a non-partisan US think tank devoted to the discussion of sustainability, development and global security.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.