Visiting Professor of Practice at LSE Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa and former CEO of Save the Children UK Kevin Watkins looks at the impact of a spiralling global hunger crisis on the health and education of vulnerable children and argues for more investment in school meal programmes.

The UN Secretary General says the world is facing ‘an unprecedented global hunger crisis.’ UNICEF warns that the lives of millions of children under five hang in the balance, as surging food prices compound humanitarian emergencies. David Beasley, Director of the World Food Programme (WFP), says the world is ‘on the brink of the abyss’ of famine. As the alarm bells triggered by the world food crisis sound with growing intensity, one constituency has been conspicuously absent: school age children in developing countries.

There’s nothing particularly new about that. When food prices soar, as they are doing now, and as they did in 2008, the cameras head for the world’s humanitarian hotspots – and not without good reason. A recent Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)-WFP report identifies 20 countries – Somalia, Ethiopia, Yemen, South Sudan among them – in which famine-like conditions are emerging. Yet, humanitarian emergencies represent the tip of a malnutrition iceberg. What is hidden beneath the surface is a worsening epidemic of hunger now destroying the education of millions of the world’s poorest children.

The ’first 8000 days’

Measuring that epidemic is not easy. As Don Bundy, a Professor of Epidemiology and Development at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, has argued, the (justified) emphasis of international agencies on nutrition during the critical ‘first 1000’ days of life is linked to an (unjustified) neglect of the ‘first 8000 days’ during which children grow, enter school, reach adolescence, and transition to adulthood.

If you’re a parent, try imagining your child sitting in a primary school or secondary school attempting to learn on an empty stomach. No, I can’t either. Yet that’s the reality millions of children face as food price inflation, economic slowdown, rising debt, and fiscal austerity take their toll across the world’s poorest countries.

There is no obvious data source for capturing the scale of crisis now unfolding, and that’s a problem that needs fixing. However, there is enough data to signal the need for action. So, here’s my best shot at the numbers.

Estimating increases in child hunger

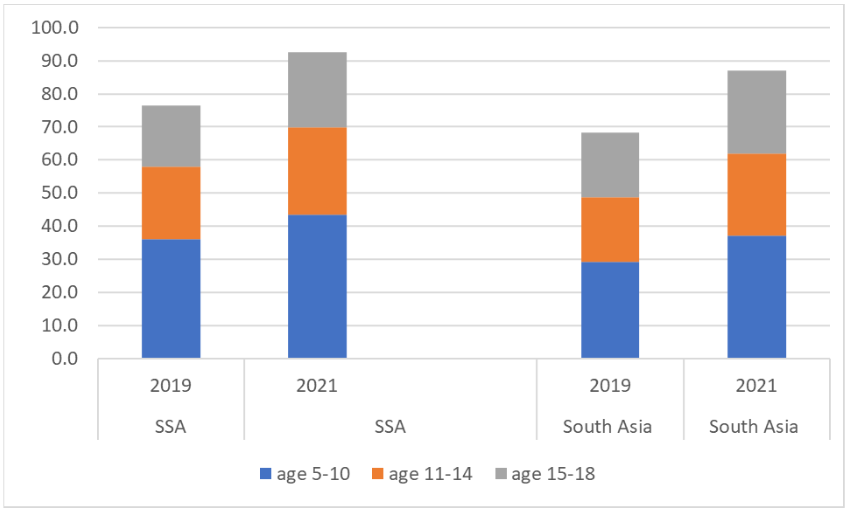

The starting point is the FAO’s recently published annual State of Food Security and Nutrition report. One of the indicators it tracks is the ‘prevalence of undernourishment’; that’s hunger by another name. I took the 2019 and 2021 reported prevalence rates for Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, which between them account for three-quarters of the world’s undernourished population and applied them to the regions’ school-age populations using data from the UN World Population Prospects. The latter step involved some sorting of cohort data to create three age clusters – 5-10, 11-14, and 15-18 – roughly corresponding to primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary schooling.

Figure 1 provides a snapshot of the results. To summarise some of the key stories behind the numbers:

- In 2021 there were 179 million school-age children living with hunger in 2021 – an increase of 35 million over the pre-Covid number.

- Primary school and adolescent children account for around 25 million of the increase.

- For southern Asia, the reversal of the past two years effectively wiped out the gains of the past seven years.

- Around one-quarter of Africa’s school-age children are now experiencing malnutrition, with the regional prevalence rate having reversed to 2005 levels.

Figure 1: Estimated undernourishment by age cohorts for sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia: 2019-2021

Before I attract the wrath and righteous indignation of the statistics community, here are a couple of admissions. Yes, the prevalence of malnutrition among school children may be different to the average regional rate. The evidence on micronutrient deficiency among adolescent girls in South Asia and Africa suggests it is probably worse. And no, linking age bands to schooling levels does not provide an entirely accurate picture of real classrooms: many children (especially girls) start school late and drop out early. Given that the social gradient in school attendance becomes steeper after the primary years as poorer children and girls drop out, the nutritional status of those not in school is almost certainly worse than those in school.

Even so, with all these (and plenty more) caveats in mind, the data points unequivocally in the direction of mass and worsening hunger in classrooms across Africa and South Asia.

Knock-on impacts of child hunger

As I argue here in the Guardian here, that has some big policy implications. Covid-related school closures in the two regions lasted far longer than in rich countries. Children, especially the poorest, have now returned to classrooms carrying profound losses in learning and the additional burden of increased hunger. And if there is one thing we know from the evidence (not to mention common sense), it’s that hungry children don’t make for good learners.

Throw into the mix rising poverty and the cuts in education budgets now underway as debt, reduced revenues, and slower growth shrink the fiscal space available to governments, and you have ‘perfect storm’ conditions for unprecedented reversals in education with the poorest children dropping out and falling further behind.

Increased hunger and the poverty that drives blocks learning and pushes children out of classrooms and into labour markets. It’s not a coincidence that the ILO recently documented the first increase in child labour in two decades. Adolescent girls face distinctive risks. Being in school is one of the most effective defences against early marriage – and those defences are crumbling.

The case for school feeding programmes

Protecting children against hunger requires policy interventions on many fronts, but one measure stands out as a source of shelter against the storm. School feeding programmes have a proven track record. They improve nutrition, increase enrolment, reduce drop-out rates, and raise learning levels.

With the right design and funding in place, they can also strengthen equity and generate benefits across generations. One recent evaluation of a school meal programme in Ghana found that all children benefited from the learning outcomes, with girls and children living below the poverty line gaining the most: the equivalent of 0.8 years of schooling. That study should be compulsory reading for policy makers who want to translate the Sustainable Development Goal slogan of ‘leave no one behind’ into something meaningful for children.

Evidence from India’s Midday Meal Scheme, the world’s largest school feeding programme, shows that feeding children in school raises learning levels and reduces stunting. Between 13 per cent and one-third of India’s reduction in stunting in the decade to 2016 can be traced to the school meals programme. More remarkable still are the benefits transferred to the children of women who participated in the programme, who are far less likely to be stunted. The reason: their mothers secure more years in school, learn more, have children later, and are more likely to use health services

Apart from the evidence that they work, one of the big selling points for school meal programmes is that an infrastructure for delivery is already in place. Before Covid-19 over 300 million children in poorer developing countries were receiving school meals. Around $5.8bn a year could restore the delivery of these to pre-Covid levels and reach an additional 73 million children.

All of which begs a question: why have donors, UN agencies, the World Bank and other multilateral development banks been so slow to act? Aid levels for school feeding are pitifully low and inconsistent, with only the US providing support on any scale, most it in the form of surplus agricultural produce. The World Bank and other multilateral development banks have no school meals strategy. Perhaps that’s because school meals cut across the absurd but deeply ingrained policy siloes that separate under-five nutrition, social protection, and education.

Whatever the underlying reasons, school meal programmes have barely figured in the planning for the fast-approaching UN transforming education summit, an event that is in grave danger of turning into a glorified talk shop. One recent summit planning jamboree at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris focussed on ‘reimagining education systems for the world of today and tomorrow.’ That’s a worthy endeavour. But imagine whatever you want – an education system scarred by mass hunger among children is a failed system.

The international complacency is reminiscent of the response of the UK government to calls for an extension of school meals during the Covid-19 pandemic: it took a Manchester United footballer to embarrass Prime Minister Boris Johnson into action. The UK’s experience is a reminder that hunger among school children is not a barrier to learning in poor countries only. As the Food Foundation has argued, there is an urgent case for extending school meals provision as the cost-of-living crisis bites and child poverty rises.

Over 120 years ago, the UK parliament adopted legislation which became a cornerstone on the modern welfare state. The 1906 Education Act, the culmination of an extraordinary campaign by a coalition of social reformers, socialist and liberal politicians, women-led voluntary, organisations, and churches, for the first time authorised the use of public funds to provide free meals for children ‘unable by reason of lack of food to take full advantage of the education provided for them.’ In the second decade of the 21st Century we have millions of children ‘unable by reason of lack of food’ to seize opportunities for education that could transform their lives, build more inclusive and equitable societies, and transform the human development prospects of their countries.

Some things in education are complicated. This isn’t one of them. Children in schools are going hungry: just feed them.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: A primary school in Lao PDR, a lunch at school. Credit: GPE/Stephan Bachenheimer via Flickr.