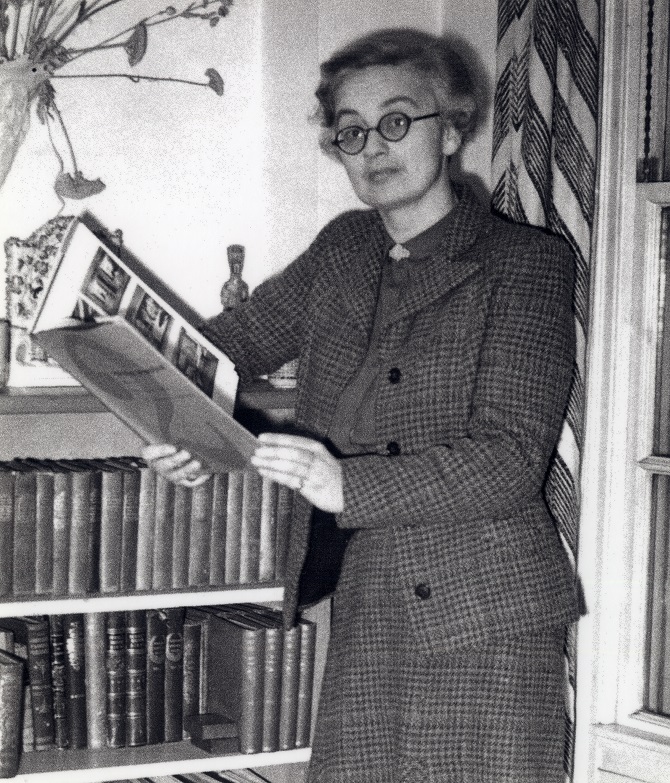

Historian Margaret Lambert gained a PhD in international relations at LSE in the 1930s and after the war spent much of her career as an editor-in-chief at the Foreign Office, specialising in contemporary German history. She also collected and wrote about English folk art with her partner, the designer Enid Marx. Dr Clare Taylor explores her fascinating life.

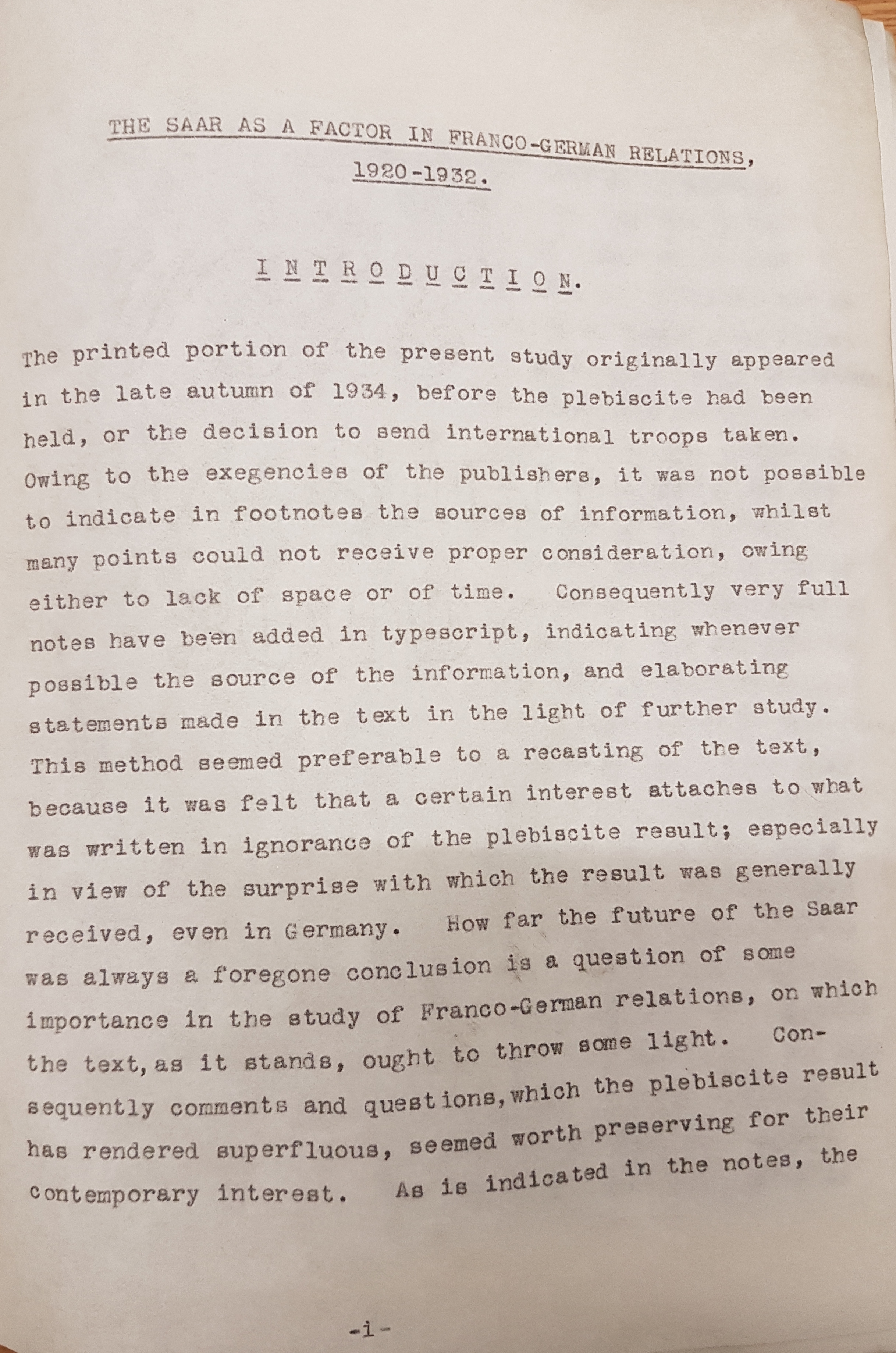

Margaret Lambert was brought up in a political household in Devon, returning to the family home there regularly throughout her life. Her father (the first Viscount Lambert) was a founder of the National Liberal party. Margaret was privately educated before studying PPE at Lady Margaret Hall. She obtained her PhD The Saar Territory as a Factor in Franco German Relations at LSE in 1936, supervised by Charles Manning. Her choice of subject reflected not only the impassioned accounts she had heard from foreign students visiting Devon in 1932, but also her father’s views on the role of international relations in the modern world.

Research on the Saar

Her research included a term in Berlin in 1933, where Manning advised her to avoid carrying a lot of notes, some of which might be incriminating, as well as in Saar itself and in Paris. Manning described her as “A thorough and energetic investigator, who will produce a well-balanced, readable book”. This book’s publication (The Saar, Faber, 1934, with a cover designed by Enid Marx, of whom more below) preceded the award of her Doctorate, timed to come out before elections in the Saar. Manning noted that her book was “very favourably received”, and Kenneth Headlam-Morley’s review highlighted its authority, based on her personal knowledge of the country and its “leading inhabitants”, as well as the access she had had to unpublished material both in the Foreign Office and in Lloyd George’s papers.

Wartime service

Lambert considered applying for a research fellowship to travel and for a lectureship in International Politics at Aberystwyth. But war intervened and instead she carried out research for the Institute of International Affairs, and became a BBC Intelligence Officer with the broadcaster’s Austrian service. Her fluent German and recent knowledge meant she was also well suited to tasks such as interviewing captured German generals over tea in country houses [1].

The Foreign Office calls

After the war, there was a proposal that Lambert write a history of modern Europe (“as the old ones are out of date”), but in 1946 she was appointed as assistant editor for the Documents on British Foreign Policy under Llewellyn (later Sir) Woodward, working with Woodward and Rohan Butler on the volumes which appeared during the late 1940s and early 1950s. The appointment came about through her old Oxford tutor, Mary Coate. Lambert wrote to her friend and literary agent, Joan Ling, that she thought the £600 pa salary was very small (she had been paid £965 pa at the BBC) but “no one hustled you and you were your own master, and could work at your leisure”. She also was anxious to establish herself in the literary world, after five years at the BBC where she had been unable to write or broadcast in her own name. However, the role of official historian was to prove no less demanding than her work at the BBC.

In 1949 she also began a University career, taking up a new Lectureship in Modern European History at Exeter. Exeter were sorry to lose her in 1951, describing Lambert as a teacher and scholar of “exceptional knowledge and experience”, but acknowledging that she was leaving to take up an “important appointment at the Foreign Office”. This was the position of editor-in-chief of the Documents on German Foreign Policy 1918-1945, a project which was to shape Lambert’s academic career into the 1980s.

Lambert’s predecessors included amongst others John (later Sir) W Wheeler-Bennett and Woodward. The aim was to publish selections which would aid contemporary historians, but listing and editing dragged on so that microfilms were often released before books. As editor-in-chief Lambert was at the centre of things; she dealt directly with Churchill over the delay in publication of the “Windsor file”, and corresponded with F H Hinsley, David Footman and others over the microfilming of, and access to, documents. She was a member of the Historical Advisory Committee on the return of the Foreign Ministry documents to West Germany, which finally began in 1956.

Issues with the return may have lain behind her decision to take up a Lectureship at St Andrews in the same year, having been first put forward for a post at Cambridge where she had advised on an extra-mural course. In 1956 there were also plans for a book with Clarendon Press, but in the event these came to nothing. However, after Woodward’s death in 1971 she completed the outstanding work on his five volume history of British Foreign Policy in the Second World War and she also contributed what F S Northedge described as a “useful” preface to the Documents on British Foreign Policy on the Young Report and Hague Conference of 1928-29 published in 1975.

An alternative identity: Folk art and Enid Marx

History was not the only string to Lambert’s bow. In the early 1930s she had met her partner, the designer Enid Marx. Both were members of a team sent out to Germany at the end of 1946, part of a Council of Industrial Design (COID) initiative to survey education in industrial design with a view to improving that at home, reflecting Lambert’s connections as much as Marx’s design experience. Other surveys followed in Sweden, Denmark and Finland, Lambert contributing essays on the Finnish (with Marx) and German trips to George Weidenfeld’s (another former BBC colleague) Contact Books. In September 1947 the pair set out for Italy, this time as a pilot study, Lambert armed with letters of introduction from the COID’s Cycill Tormley, hotel recommendations from Veronica Wedgwood and contacts in Radio Italiano from her BBC days.

With Marx, Lambert also developed a very different area of expertise in the study of popular art and vernacular life. Collecting and writing about this field was a key part of Marx and Lambert’s private and public collaboration as modernist designer and modern historian, celebrated today in the Marx-Lambert collection at Compton Verney.

In 1979 Lambert recalled that they had begun collecting together for a book celebrating the centenary of Victoria’s accession, When Victoria Began to Reign: A Coronation Year Scrapbook made by Margaret Lambert published by Faber in 1937 in time for the Coronation of George VI. Lambert and Marx went on to produce two books together, English Popular and Traditional Art (1946), part of the “Britain in Pictures” series, expanded as English Popular Art (Batsford, 1951, reissued with a new foreword by Merlin Press, 1989), and a chapter on the same subject in W J Turner’s British Craftsmanship of 1948. There were plans for another jointly authored Batsford book on Victorian Antiques, but despite much research and photography these came to nothing as Lambert suffered from ill health during the 1950s.

Marx also designed bookplates for Lambert; in one the message for the historian around a dish of carp was “Carpe Diem”, in another the two heads of Janus. However, her memorial at St Michael’s, Spreyton, commissioned by Marx and executed by Judith Verity, reads simply “In memory of Margaret Lambert, Historian 1906-1995”.

References

[1] Eleanore Breuning, “Margaret Lambert”, obituary, The Independent, 1 February 1995

LSE archive, Margaret Lambert’s PhD file

Enid Marx Archive, V&A Archive of Art and Design

Breuning-Eve bequest, Pallant House

University of Exeter, Special Collections, University College Annual Reports 1949-51

D Cameron Watt, “British historians, the war guilt issue, and post-war Germanophobia: A documentary note”, The Historical Journal, 36:1 (1993), 179-85

Astrid M Eckert, The Struggle for the Files: the Western Allies and the return of German archives after the Second World War, trans. Dona Geyer (German Historical Inst. Washington, DC and Cambridge University Press, 2012)

Alan Powers, Enid Marx: The Pleasures of Pattern (Lund Humphries, London in association with Compton Verney)

This article was originally published on the LSE History blog in 2018.

Browse the collection of blog posts about LGBTQ history at LSE.