One of Donald Trump’s signature policies during the Republican’s presidential primary race has been the construction of a border wall with Mexico, which he claims would end the flow of undocumented immigrants into the US.Marc Hooghe and Sofie Marien write that it does not matter whether the ‘Wall with Mexico’ can actually be built; instead it is a utopian metaphor for the kind of closed society that Trump’s supporters wish to live in.

One of Donald Trump’s signature policies during the Republican’s presidential primary race has been the construction of a border wall with Mexico, which he claims would end the flow of undocumented immigrants into the US.Marc Hooghe and Sofie Marien write that it does not matter whether the ‘Wall with Mexico’ can actually be built; instead it is a utopian metaphor for the kind of closed society that Trump’s supporters wish to live in.

One of the boldest proposals that has been put forward an already extraordinary presidential campaign thus far, Donald Trump’s plan to erect a wall on the border between the US and Mexico, in an effort to keep out illegal immigrants. Although at first sight, this seemed like a nonsensical proposition, Trump has since repeatedly addressed the issue, claiming that he indeed wants to build the wall, insisting that the Mexican government, in some way or another, would pay for the construction of this border protection device.

The proposal, and the way it has been received by the Trump supporters, poses a challenge for professional observers of the presidential campaign. The broadsheet media quickly pointed out that the proposal wasn’t feasible. Not only the cost of such a construction would be prohibitive, the US federal government does not even own the land where the wall should be built, and furthermore there is no reasonable person who actually imagines that the Mexican government will be inclined to pay for its construction. For professional political scientists and broadsheet journalists, all these problems effectively killed the entire idea. However, surprise, surprise: candidate Trump simply went on to repeat the proposal, and the crowds at his rallies remained enthusiastically as ever as they went on cheering this proposal. While the professional observers were already flabbergasted by the proposal itself, they were even more surprised by the fact that their comments and serious criticism did not seem to have any effect at all, as they were simply ignored by a vast majority of the Trump supporters.

The currently available research on political communication and media effects offers us a number of clues on how to understand this lack of understanding between voters and professionals. First of all, it should be remembered that most US voters are not all that well informed about politics at all. So while the readers of this blog will be familiar with the empirical objections against the wall proposal, by no means it should be taken for granted that the median Trump supporter has been confronted with this information. Second, we also know that partisans tend to disregard information that runs counter to their own beliefs. So even if Trump supporters are exposed to all the necessary information about the lack of feasibility for this proposal, they will still be inclined to question the reliability of this information. While this is a very general mechanism in the field of political communication, it is all the more important in this specific case. In his campaign rhetoric, Mr. Trump has claimed repeatedly that the “elite” media purposely distort his message, as their aim is to protect the status quo. This provides his supporters with all the more reason to disqualify the information that is being sent out by the mass media. The strategy of blaming the “elite” media because they are biased further strengthens the process whereby information that runs against one’s pre-existing ideas is discounted. One could even say that it institutionalizes the psychological mechanism to disregard new information that runs counter to one’s ideological beliefs.

Why information does not have an effect

While the debate about the wall might adhere to these general rules of political communication, the wall project does offer a highly specific case. For various other policy proposals, exactly the same mechanism might be at play, but the difference is that most of these other proposals are inherently technical and complex, so there is ground for reasonable debate and disagreement. If Senator Sanders proposes to break up the major banks, various think tanks and lobby groups, and established economists like Paul Krugman, are quick to point out that this will not be feasible and might entail serious harm to the economy. For someone who does not have a degree in economics, it is quite hard to tell who is right and who is wrong in this debate. The difference with the wall is that this proposal is so darn palpable: everyone knows what a wall is, what kind of effort it takes to construct one, and what kind of investment is involved. One does not need a degree in engineering to understand what a 2000 mile wall would look like, and what would be the effort required to construct it.

So we are left by the puzzle that all the rational objections against the wall proposal do not seem to have a significant impact on public opinion. In order to understand this, it is important to have a look at the research literature on populism and populist rhetoric. One of the defining features of populism is that it rejects this kind of reality check: populist proposals typically appeal to emotional sentiments, rather than to standard institutional mechanisms. The appeal of populism to a large extent is indeed that it offers the opportunity to escape the incremental muddling through that is so typical of institutional politics. Populism, almost by definition, feeds on radical proposals and the question whether or not these proposals are feasible runs against the basic emotional appeal of this rhetoric.

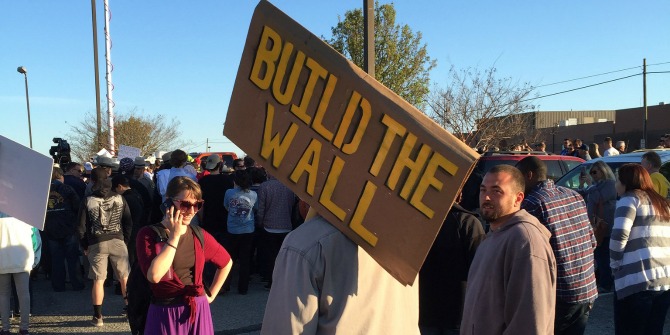

Credit: Forsaken Fotos (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Longing for a closed society

In this specific case: the wall proposal is not meant to be a realistic proposal, and it is not judged that way by all the supporters, and it has never been meant to be a realistic proposal. The wall is a utopian metaphor for what an ideal society should look like. For someone who is very strongly concerned about crime, drugs, unemployment, the rise of Spanish language rights in US society, and increasing diversity, the wall offers a perfect metaphor: would it not be perfect if we could just build a wall to keep all these dangers outside, so that we can continue to live our perfectly tranquil small town American life? The populist message of the wall proposal is basically that it is possible to return to a way of life that has disappeared, because of increasing globalization, economic flows and demographic change.

The utopian character of the proposal also explains why criticisms from mainstream media often backfires, as the critique is seen as a rejection of one’s preferred way of life. Saying that the wall cannot be constructed basically amounts to the rejection that this idealized homogeneous and closed way of life can be reached. Some groups of the population have a strong preference for a rather closed and homogeneous society, and it has to be noted that in such a closed society strong bonds of solidarity can indeed exist. One could hardly think of a better metaphor for a closed society than simply building a wall around that secluded piece of land, where one can continue to live without being bothered by globalization, diversity and other structural trends that might seem frightening.

The misunderstanding on the utopian character of the wall is to a large extent due by our tendency to restrict the use of the word ‘utopia’ to those ideals that we agree with. This is however, not the way the word was originally introduced exactly 500 years ago in ‘Utopia’ by Sir Thomas More. Any ideal society can be labelled a utopia, whether we share those ideals or not. The concept of utopia simply refers to the reification of a concept that is considered to be ideal. Intellectuals like the ‘I have a dream’ rhetoric about white and black children going hand and hand together to school. This kind of dream is thought to be inspiring and important. But other people also have dreams, about white and white children going hand in hand to an all-white school, with no black or Latino children in sight.

The wall, therefore, is the exact opposite of the utopian project that is engrained in our collective memory. If Donald Trump would have more rhetorical talent, he might even defend his proposal with exactly the opposite words as the famous speech of more than half a century ago:

I have a dream that one day, up in New York State, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of multiculturalism and minority rights – one day right there in New York, little white boys and girls will be left alone, with other white boys and white girls as only sisters and brothers. I have a dream that one day every valley will be closed, and that on every hill and mountain there will be a fence, and that we can just live the life we have lost.

Most of us will be appalled at reading words like these, but we should realize that for some groups of the population the appeal of a homogeneous society is just as strong as the appeal of a society without prejudice is for others.

The utopian character of the proposal also implies that if we want to investigate the apparent success of the Trump campaign, and some of his other less realistic proposals, there is no need to invoke specific US arguments, as to a large extent the Trump campaign can be seen as a typical example of the populism that is also present in other liberal democracies. The disenchantment with institutionalized liberal democracy seems to be so strong that non-realistic proposals are seen as highly attractive by a relatively large segment of the population. Populist parties in France and Germany too, have voiced proposal that are clearly not feasible. Pointing this out, however, has not made an impact on the popular appeal of these proposals. The lesson to be learned is that rational arguments will not convince anyone, not even in this case. Rational arguments about the cost of the wall, and how high it should be, and how it will fail to stop immigration, will not be interpreted as rational arguments, but rather as a rejection of a longing for a closed society, that no longer exist or can exist. The real problem is not how high the wall will be, but rather how the desire for a closed society can be responded to in a liberal and globalized society.

This article was originally published on the USAPP blog.

Note: the views expressed here are those of the authors alone and do not reflect the position of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

_________________________________

Marc Hooghe – University of Leuven

Marc Hooghe – University of Leuven

Marc Hooghe is a professor of political science at the University of Leuven (Belgium), and he has published mainly on participation, political attitudes and the democratic linkage between citizens and the state.

Sofie Marien – University of Amsterdam/University of Leuven

Sofie Marien – University of Amsterdam/University of Leuven

Sofie Marien is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Amsterdam, the University of Leuven, and a Visiting Professor at the University of Pennsylvania.