The international community must reassess the developmental aid system to take account of the vulnerability of specific regions to the effects climate change, regardless of their income status, writes Polly Hatfield.

The international community must reassess the developmental aid system to take account of the vulnerability of specific regions to the effects climate change, regardless of their income status, writes Polly Hatfield.

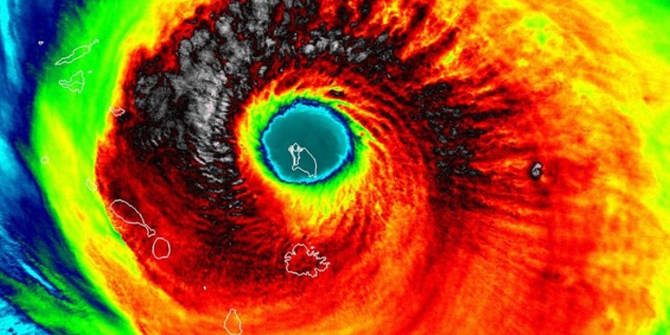

Citizens of Caribbean states are used to living with the threat of destructive weather events. Hurricane Irma, however, stands out as the most severe Atlantic Ocean hurricane on record. The storm has caused at least 37 deaths across the Caribbean and has devastated small island communities, with the Red Cross appealing for 1.1m Swiss Francs (US$1.15m) to provide vital sanitation equipment and emergency shelters.

Irma throws into sharp relief the need to re-evaluate the criteria according to which Official Development Assistance (ODA) is distributed. The challenges faced by developing nations today call for a more nuanced approach to aid eligibility which looks beyond Gross National Income per Capita, and takes into account national and regional vulnerability to catastrophic events such as hurricanes.

International institutions and regional governments agree on the need to invest in climate-proof infrastructure and hurricane preparedness measures in the Caribbean. The UK Caribbean Infrastructure Partnership Fund (UKCIF), a £300m investment programme launched by David Cameron in September 2015, is just one example. It offers grant financing for infrastructure projects, prioritising those that provide ‘increased resilience to climate change in the Caribbean’. Elsewhere, the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) recently approved a new grant financing scheme for disaster risk management projects in the Caribbean’s poorest nation, Haiti.

However, these programmes can only go so far in protecting the Small Island Developing States of the Caribbean from natural disasters. Despite the region’s intrinsic vulnerability to extreme weather events, several Caribbean nations are currently classified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as high-income countries, rendering them ineligible for ODA. These include Antigua & Barbuda, one of the states worst hit by the hurricane, alongside The Bahamas, Barbados, St Kitts and Nevis, Trinidad and Tobago.

The UN definition of Least Developed Countries (LDCs) references these nations’ low levels of foreign investment, heavy debt burdens, lack of economic diversification, and vulnerability to ‘external terms-of-trade shocks’. Haiti is currently the only Caribbean country classified as an LDC.

Whilst it would be wrong to argue that the advanced, service-oriented economies of much of the rest of the region warrant reclassification as LDCs, it is nonetheless important to acknowledge that several Caribbean states suffer from the same systemic disadvantages as the world’s poorest nations. These include sustained budget deficits and high levels of public debt: in Jamaica, for example, accumulated debt reached 145% of GDP in 2012, according to The World Bank.

Moreover, the Caribbean continues to struggle with a lack of economic diversification. The drop in international gold and oil prices has sent commodity-dependent Suriname into an economic crisis, with inflation reaching 77% in September 2016. The country’s economy shrunk by 10.4% in 2016, following on from a 2.7% contraction the previous year. Oil- exporting Trinidad and Tobago is facing similar challenges, with GDP falling an estimated 2.8% in 2016 and a contraction of approximately 10% in the energy sector alone.

Tourism remains a major source of growth, investment, and foreign exchange for the Caribbean. The World Travel & Tourism Council estimates that the sector contributed US$801.4m to the economy of Antigua and Barbuda in 2016 (60.4% of total GDP), whilst in St Lucia, tourism generated some US$572.2m, or 39.6% of total GDP. However, the predominance of the hospitality industry exacerbates the vulnerability of tourism-dependent states to external economic shocks and extreme weather events, which destroy crucial infrastructure and accommodation facilities.

The UN argues that officially denominated LDCs require international support to address the fundamental challenges of armed conflict, political instability, and weak governance. For the Small Island Developing States of the Caribbean, however, it is climate change that presents the greatest threat to further equitable growth.

The region has proactively and determinedly engaged with international initiatives to promote sustainable environmental practices and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has commended the ambitious plans of Latin American and Caribbean governments to reduce carbon emissions through new policy measures, including carbon pricing mechanisms. Grenada, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent & The Grenadines were some of the first nations to ratify the Paris Climate Change Agreement.

Governments are also turning to green energy sources as a possible means of cutting electricity prices in a region where tariffs have historically been disproportionately high. As part of its Vision 2030 plan, the government of Jamaica aims to source at least 20% of its electricity needs from renewables by 2030. Grenada has gone even further and intends to meet 100% of its electricity requirements from renewable sources, primarily geothermal and waste-to-energy, by 2030.

It is time that the international community reassessed the developmental aid system to take account of the vulnerability of specific regions to the effects climate change, regardless of their income status. Hurricane Irma is a clear indication that the developmental achievements of recent governments in the Caribbean are at risk from extreme weather events. The region itself is already taking proactive steps to engage with international climate initiatives. But by supporting regional governments to invest in climate change resilience and damage-limitation measures, the international community will avoid having to face the far greater cost of providing emergency aid and humanitarian assistance in years to come.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Polly Hatfield

Polly Hatfield

Polly Hatfield is a former Research Analyst of The Caribbean Council, a not-for-profit consultancy working with public- and private-sector organisations in Central America and the Caribbean. She has an MSc in Theory and History of International Relations from the London School of Economics and Political Science.