Miguel Díaz-Canel’s presidency is likely to represent a continuation of the “negotiative process” that has allowed government and society alike to adapt to evolving challenges ever since 1959, write Emily J. Kirk (Dalhousie University) and Isabel Story (University of Nottingham).

Miguel Díaz-Canel’s presidency is likely to represent a continuation of the “negotiative process” that has allowed government and society alike to adapt to evolving challenges ever since 1959, write Emily J. Kirk (Dalhousie University) and Isabel Story (University of Nottingham).

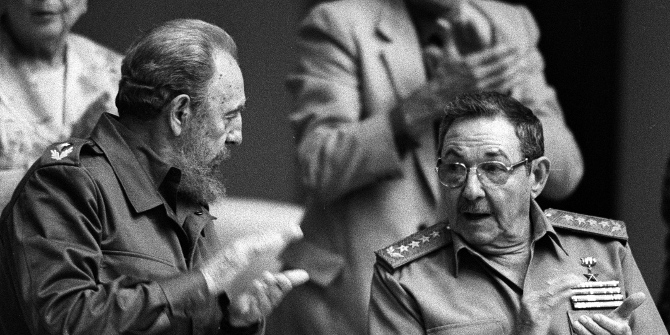

Since 1959, Cuba has been synonymous with the name “Castro”. First, because of the charismatic Fidel Castro, who led the Revolution until 2006, and then for his pragmatic brother Raúl, who added the presidency to his leadership of the Revolutionary Armed Forces in 2006 (officially 2008).

They first came to international attention as guerrilla fighters seeking to revolutionise an economically and socially divided Cuba during the 1950s, when it was effectively under US neocolonial rule. While Fidel occupied the spotlight, lauded and demonised in equal measure, Raúl also played an active part in shaping the revolution, its ideology, and its international relations.

But in March 2018, Cuba’s complex election process kicked into action, first with elections for neighbourhood representatives, then filtering up to the municipal level, before finally electing the 605 members of the National Assembly. On 18 April 2018 the National Assembly voted to nominate the candidate for the presidency, as well as the members of the Council of State, and the following day that presidential candidate, Miguel Díaz-Canel, became the new president.

Both the date and the candidate are significant. Crucially, Miguel Díaz-Canel is the first non-Castro to lead Cuba, and he is also too young to have participated in the 1953-1958 rebellion. But his ascendance to the presidency also coincides with the dramatic failure of the CIA-funded Bay of Pigs Invasion in 1961, which sought to end the revolution and oust the Castro leadership. This anniversary is particularly significant given the increasing hostility of US relations towards Cuba under the Trump administration, which are thrown into particularly sharp relief by the well-publicised efforts of Barack Obama, Raúl Castro, and Pope Francis to improve relations between 2014 and 2017.

The past and future of President Miguel Díaz-Canel

It is no surprise that Miguel Díaz-Canel was elected, both because he enjoyed the support of Raúl Castro himself and because he has been a very active member of the Cuban Communist Party for some 30 years.

He trained as an electrical engineer, served as Minister of Higher Education between 2009 and 2012, and was elected First Vice President of the Cuban Communst Party in 2013, occupying key posts at difficult times.

He has been described as “plainspoken”, “moderate”, and “pragmatic”. As former Canadian Ambassador to Cuba Mark Entwistle has noted:

He does not come from the older generation of the kind of guerrilla fighters from the mountains who derive a lot of their legitimacy from that historical experience … He comes from a different place, he has a very different style, a different way of presenting himself, and he’s not from the same centres of political power.

But it is also important to consider that having been born in 1960, Díaz-Canel remains a product of the revolution, and indeed he has been a vociferous defender of it.

Thus, despite this significant shift in leadership – itself belying the idea of the Cuban presidency as a dynasty – it is unlikely that any dramatic changes will take place in the short term. Instead, Díaz-Canel is likely to push ahead with reforms outlined by Raúl Castro’s government, such as internet access, land reform, and increased private economic activity. This echoes Raúl Castro’s strategy for a “slow but sure” revolution that changes continuously but cautiously.

It is also important to remember that even though Díaz-Canel is now president, Raúl Castro will remain a figure of great importance. He will stay on as leader of the Communist Party of Cuba and as leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, with the latter playing an important role systematising organisation and accountability across many areas of state provision.

Old challenges for Cuba’s new president

While Díaz-Canel may be new to the presidency, the challenges his government faces are longstanding.

The main problems include ongoing hostility from the US government, housing, transportation, and a dependent economy. Particularly pressing and difficult will be reorganisation of the island’s controversial dual-currency economy, which has led to widening inequality between those paid in local and dollar-convertible currencies. Again, this was a change mooted under Raúl Castro, but a concrete plan has yet to be implemented.

On the social front, the new president also faces doubts about the loyalty of the younger generation. As the scholar and former Cuban diplomat Carlos Alzugaray noted in an interview with CNN, “in my time, when Fidel or Raúl said something, I would do it, even if I had second thoughts; is that how the younger generation […] is going to react to what Díaz-Canel says?” It may no longer be enough to please the older generation of staunch revolutionaries.

Overall, Cuba may change, but not dramatically. It is important to recognise that the Cuban Revolution is a “negotiative process” that has survived so long because of the ability of country and government alike to adapt to evolving challenges, usually through periods of prolonged debate.

While it is unclear what particular point or event could mark the end of the Cuban Revolution, Díaz-Canel’s presidency and the end of the “Castro era” are more likely to represent the same combination of continuity and change that has characterised revolutionary Cuba ever since 1959.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

First of all I would like to refer you to the writers of this article. The birth of the Republic Cuba was May 20, 1902 led by our parents of our country Jose Marti. Martí said that “in order to know a people, it must be studied in all its aspects and expressions: in its elements, in its tendencies, in its apostles and in its bandits”. Since the founding of the Communist Party of Cuba, while the Marti cult was growing, the Creole Marxists maintained the greatest reserve, if not hostility, towards the apostle of Cuban liberties.

The question of rigor to the Ladies. Emily J. Kirk and Isabel Story would be: Opening for whom? Opening how? For the people on foot victim of the Castro-Fascist military Consortium that sells basic necessities with 200% over the purchase price? A working people that receives an average salary that does not exceed $ 30 USD per month. Will this be the openness and respect to which the Ladies referred. Emily J. Kirk and Isabel

Another recent shamelessness to emphasize, comes from a work published by the official Granma newspaper that signed by Enrique Ubieta and had the title, “Is it possible to unite the best of capitalism and socialism?”.

In his work, Ubieta affirms this flagrant falsehood. He says that: “Cuban capitalism, as in the past, can only be neo-colonial or semi-colonial. The only way for the bourgeoisie to retake and maintain power in Cuba is through an external power; it is the only option to reproduce its capital, and we already know that the Homeland of the bourgeoisie is capital “.

Perhaps Comrade Ubieta, when speaking of external power, refers to the Soviet empire, via primacy, from which, the leader and directly responsible for the disaster enthroned in Cuba, the happily deceased Fidel Castro, retained absolute power for several decades until the happy collapse of that nightmare, the right moment to look for and find the next external way of support and support.

Mr. Ubieta conceals the current transition from the always failed real socialism, Marxism, Leninism, etc., to the fascist corporate system of state capitalism without rights or freedoms inaugurated in Germany and Italy by Hitler and Mussolini in the first half of the 20th century and today renamed as socialism of the 21st century or reformulated from mendacious guidelines. Transit initiated by the Castroite elite from its military oligopoly and its absolute police control.

The shamelessness never comes alone and so we put these, to the consideration of such patient and respected readers, that if they do not live in Cuba, they will see everything with distance and it is possible, even with empathy. It would only be necessary to see who will be the repositories of such empathy, the victims or the professionalism and charisma of the perpetrators.