Since the end of the Stroessner dictatorship in 1989, the surge in Brazilian economic, political, and cultural influence has been so pronounced as to make Paraguay almost a client state of its more powerful neighbour. This is clearest in the unequal outcomes of the Itaipú Treaty on joint hydroelectricity generation and in the untrammelled political power of Brazilian-Paraguayan agribusiness in the soybean export sector, but renegotiation of Itaipú in 2023 could be the start of a shift in bilateral relations, writes Andrew Nickson (University of Birmingham).

Since the end of the Stroessner dictatorship in 1989, the surge in Brazilian economic, political, and cultural influence has been so pronounced as to make Paraguay almost a client state of its more powerful neighbour. This is clearest in the unequal outcomes of the Itaipú Treaty on joint hydroelectricity generation and in the untrammelled political power of Brazilian-Paraguayan agribusiness in the soybean export sector, but renegotiation of Itaipú in 2023 could be the start of a shift in bilateral relations, writes Andrew Nickson (University of Birmingham).

In the two and a half months since Jair Bolsonaro assumed office in Brazil on 1 January 2019, he has already met three times with his counterpart in Paraguay, Mario Abdo Benítez. The frequency of these bilateral talks reflects an issue of considerable geopolitical concern to Brazil: the imminent renegotiation of the 50-year Itaipú Treaty, set to expire in 2023.

Itaipú Binacional: when some partners are more equal than others

Under the terms of the Itaipú Treaty, signed in 1973 by the military governments of Paraguay and Brazil, the two countries agreed to develop the enormous hydroelectric resources of the River Paraná on their shared border. This led to the construction of what remains the world’s largest hydroelectric plant, which still produces more electricity than China’s massive Three Gorges dam. Yet, right across the political spectrum in Paraguay the treaty continues to be seen as an affront to national sovereignty.

The joint-ownership terms of Itaipú Binacional, the hydroelectric company set up to administer the plant, mean that each country owns half of the energy produced. But the treaty also states that any energy surplus to the requirements of either country must be sold to the other country, whereas sales to third party countries are prohibited. The price of such sales, euphemistically referred to as “compensation payments”, is based on the cost of production and not the regional market price for energy.

As a result of these extraordinarily unequal terms, for decades Paraguay has effectively subsidised the industrial growth of the São Paulo metropolitan area. In 2018, 85 per cent of Paraguay’s share was still ceded to Brazil. Combined with the its own share, Itaipú accounts for 15 percent of total electricity consumption in Brazil.

The brasiguayo factor

Relations between Paraguay and Brazil have been further complicated by a massive cross-border migration of Brazilian farmers and agribusiness companies since the 1970s, initially into the eastern border area near the Itaipú Dam itself but later extending west across the country and into the far north of the Paraguayan Chaco. There are now around 500,000 Brazilians, known as brasiguayos, in Paraguay.

Unlike most other migrant groups in Latin America they tend to have a much higher standard of living than the local population. Brazilian migration has transformed the agricultural economy, turning Paraguay into the world’s fourth largest exporter of soybean, of which some 95 per cent is produced by brasiguayos.

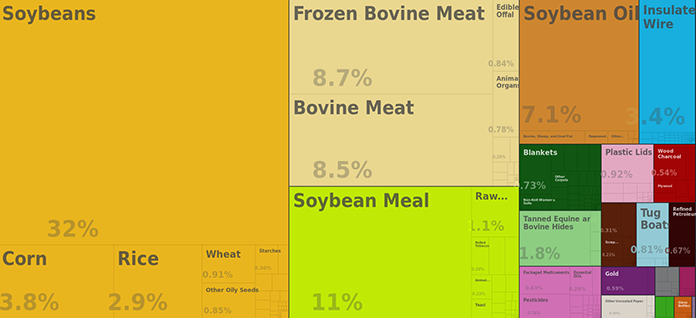

But despite soy and its derivatives accounting for roughly half of Paraguay’s total merchandise exports (as illustrated below), soybean farmers contributed only two per cent of total tax revenue in 2018, and they remain bitterly opposed to a proposed ten per cent tax on agricultural exports. On several occasions since the late 1990s, the Soybean Growers Association coordinated the blocking of major highways by hundreds of tractors in order to ward off legislation that would bring soybean growers under the tax net.

Brasiguayos have also been engaged in bitter land disputes with landless families over so-called “ill-gotten lands” (tierras malhabidas). The term refers to eight million hectares of virgin forest illegally distributed to “family and friends” of the Stroessner dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s under the cynical guise of land reform. More recently, much of this land has been purchased by brasiguayos, who have increased their holdings by buying up provisional land titles (derecheras) from impoverished small farmers.

Radical peasant groups have responded by stepping up land invasions to reclaim these properties for the poor and landless that were supposed to benefit from the original land-reform legislation. Small farmers’ organisations and environmentalists also criticise the environmental degradation caused by soybean monoculture, accusing brasiguayos of flouting laws designed to halt deforestation, using illegal genetically modified crops, and poisoning poor rural communities through the uncontrolled use of pesticides and aerial crop spraying.

The brasiguayo backlash and the Paraguayan People’s Army

More recently, the westward expansion of the brasiguayos has encountered stronger opposition from more densely populated and consolidated small-farmer communities in the northern departments of San Pedro and Concepción. This “clash of cultures” was a major factor in the emergence there of a low-level insurgency movement, the Paraguayan People’s Army (EPP).

Although it shares the triple cocktail of radical Catholicism, Marxism, and nationalism with many Latin American insurgencies during the Cold War, the EPP ideology also incorporates an extra “geopolitical” ingredient: the pursuit of what it calls the “second independence” of the country.

This became a potent message that resonated with the “common sense” understanding of Paraguay’s distinctly martial history. It draws a parallel between a “first” invasion of Paraguay during the Triple Alliance War of 1865-70 and a “second” invasion of brasiguayos in recent decades.

In the first case, Brazilian troops sacked Asunción in January 1869, occupying the capital for six years after the war ended. They also carried out atrocities that are still deeply embedded in the Paraguayan psyche. After the war, Brazil took possession of over 60,000 square kilometres of Paraguayan territory, 25 per cent of its pre-war area, which went on to become part of Brazil’s Mato Grosso state. Brazil has never apologised for alleged acts of genocide nor returned the wealth of “war trophies” plundered from the defeated nation.

Today, brasiguayo commercial farmers are a major target of the EPP, forced to pay a “revolutionary tax” and warned on pain of death not to plant genetically modified crops or to deforest the land they occupy.

Overall, the democratisation of Paraguay since the end of the long Stroessner dictatorship (1954-89) has seen a surge in Brazilian economic, political, and cultural influence in Paraguay. This has been so pronounced that Paraguay could be considered a “client state” or even a “protectorate” in its relationship with Brazil.

Paraguayan political postures on bilateral relations

A succession of elected presidents has failed to question the terms of the Itaipú Treaty or the role of the brasiguayos. The only exception was President Fernando Lugo, elected in 2008 but removed via a lightning-quick impeachment in July 2012. Intense lobbying by the Soybean Producers Association against his efforts to tax the brasiguayos and investigate the legality of their land titles was a major yet under-reported factor in his overthrow.

President Abdo Benítez, meanwhile, was elected in April 2018 and leaves office in 2023 just as the Itaipú Treaty expires. Owing to Bolsonaro’s strident nationalist discourse and his appointment of hardliner General Joaquim Silva e Luna as the new director of Itaipú Binacional, Abdo Benítez is facing intense political pressure to adopt a firm stance in renegotiating the treaty.

In a positive sign, he has appointed Professor Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University as an energy adviser. In 2013, Sachs wrote a forensic report on the Itaipú Treaty, concluding that Paraguay had long since paid its share of the Itaipú Binacional debt through its grossly underpriced energy sales to Brazil. Abdo Benítez’s decision to personally lead the negotiations has raised eyebrows, however, giving rise to fears of a potential sell-out.

Two key issues are crucial to demands for a reassertion of national sovereignty:

- Paraguay must be allowed to sell its surplus from Itaipú to third countries, such as Chile and Uruguay.

- Energy sales to Brazil should be based on the “opportunity cost” to Brazil of sourcing energy from elsewhere. In 2018, for example, Argentina sold power to Brazil through the Garabi converter station at USD $120 per megawatt hour (MWh), whereas Paraguay continued to cede its surplus energy from Itaipú to Brazil for a measly USD $8 per MWh.

Brazil’s foreign ministry, Itamaraty, has long been successful in projecting a benign image of the country’s engagement with the outside world, most recently stressing its commitment to a “Global South” agenda. While other BRIC countries have attracted negative attention for ill-treatment of smaller neighbours – Russia with Chechnya, India with Nepal, China with Tibet – Brazil has avoided this kind of condemnation.

Brazilian vice-president Hamilton Mourão recently stated that “Brazil has a long tradition that we don’t intervene in the internal affairs of other countries”, yet even a cursory examination of the country’s historical relationship with Paraguay raises serious doubts about this externally projected “soft power” image. The upcoming renegotiation of the Itaipú Treaty will provide clear indications of whether Paraguay’s current “direction of travel” towards a protectorate relationship with Brazil will be halted or even reversed.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Sadly, here we are deep in 2022 and where is the transparency over the negotiations, the stated positions, the actual negotiations? It is like a black hole. As Brazil prepares for an Oct ’22 election and Paraguay for an Apr ’23 election.