Brazil’s 13 million favela dwellers have often been asked to show resilience in the face of the country’s sharp inequalities. Getting through the coronavirus crisis, however, will require more than the ability to make ends meet. Community-based initiatives have done much to protect local people from the most damaging impacts of the Bolsonaro government’s deficient response and toxic rhetoric. But now as in the long term, the deep inequalities revealed by coronavirus must be kept visible and properly addressed, write Aiko Ikemura Amaral (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre), Gareth A. Jones (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre), and Mara Nogueira (Birkbeck, University of London) as part of a series of blogs linked to their British Academy-funded project Engineering Food: infrastructure exclusion and ‘last mile’ delivery in Brazilian favelas.

In Brazil, the COVID-19 pandemic has become an integral part of a political struggle involving politicians across the board. But even though “the war against coronavirus” has become a means of gaining political capital, concrete responses from the government have been both lagging and lacking.

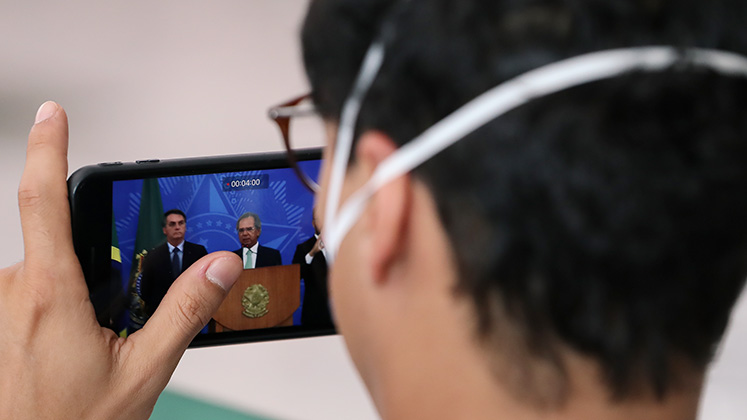

The first week of April saw some measures begin to be implemented, not least the distribution of monthly vouchers worth R$600 (less than £100) to those financially affected by the coronavirus. Appealing to Brazilians’ sense of kindness, Minister of Finance Paulo Guedes asked the population to help those he called “the invisibles” to register for the voucher via smartphone apps. Guedes’ misplaced insinuation was that this population either lacked smartphones or were not themselves smart enough to follow the guidelines issued by the government.

But who are “the invisibles”? According to Guedes, these are the people who “never asked for anything, [who] never needed the government … a cleaner, a cab driver, a street vendor.” This rhetorical acknowledgement of informal workers is revealing of his disconnect with the working classes in Brazil, whose contributions are central to the country’s economy and society.

Yet in favelas, where the eyes of the state have rarely fallen, a number of collaborative, community-based initiatives to counteract the impacts of the disease have emerged and flourished. For those who were already struggling to get by without coronavirus, however, invisibility before the state is not just a cause for resilience and resourcefulness but also a product of deeper socioeconomic inequalities and restricted access to rights. The virulence of COVID-19 does not make it more democratic in highly unequal societies: collective action is required, and fast. But getting through the pandemic will need more than just bottom-up solutions from low-income Brazilians and the few limited measures already adopted by the government.

Lives and livelihoods in favelas

Stark socioeconomic inequalities have a direct impact on health and wellbeing, and these socioeconomic disparities are most graphically revealed by Brazil’s classic asfalto–morro divide: that is, between the formal, tarmacked city (asfalto) and the improvised favelas climbing the hillsides (morro).

Even before COVID-19, the higher prevalence of other infectious conditions like tuberculosis (TB) in favelas has been an underlying cause of public health concern. Rocinha, the biggest favela in Rio de Janeiro, for instance, has an annual TB notification rate five times higher than the citywide average. Sadly, but perhaps unsurprisingly, existing data on COVID-19’s death toll indicates that the mortality rate is considerably higher in low-income areas of Brazil’s largest cities.

Yet, favelas are not homogeneously destitute spaces, and broader inequalities are also reproduced across and within favelas. This becomes evident in the very architecture of houses.

While some homes are built of brick-and-mortar and can cost tens of thousands of Brazilian reais, more recent constructions are usually made of less-durable materials and located in more hazardous areas considered “at risk”, such as floodplains or steep slopes. For some favela residents, lajes – concrete slabs serving as rooftops – provide much-needed respite from the lockdown, with residents able to socialise, go about their everyday chores, or live-stream funk concerts via social media. For those who do not own a laje, the streets – usually bustling with commerce, services, and people – are still the place to go out and get some fresh air.

The centrality of the street in peoples’ everyday lives goes beyond its economic importance: streets are spaces of conviviality, community-building, and organising. Indeed, social media posts with the hashtag #COVID19nasFavelas suggest that these spaces remain very lively, despite growing awareness of the virus.

But busy streets also suggest that the “stay at home” guidelines issued by city mayors and state governors also present other serious threats to people’s subsistence. In favelas, the majority of self-employed and informal employees (respectively 47% and 8% of favela residents) rarely have the option of working from home. While some continue to risk infection on public transport and at work, others have no choice but to close their businesses or lose their jobs. The connection between these two dimensions – sociability and liveability – is thrown into ever starker relief as small entrepreneurs and workers see their incomes threatened by COVID-19’s looming socioeconomic effects.

The pervasiveness of so-called viração – making ends meet through a variety of precarious jobs despite the difficulties – can be taken as a sign of Brazilian inventiveness and resilience, but it is also a clear indication that material resources and economic opportunities do not trickle down to the poorest.

A month into quarantine measures in a number of states, 72 per cent of favela residents had already experienced a deterioration in their living standards. The same research also indicated that 92 per cent of mothers living in favelas believed they would not be able to access staples, including food, if they were to lose their incomes for another month. In the absence of more comprehensive social security programmes, favela residents are left with a false – and yet all too real – choice between their lives and their livelihoods.

Bottom-up initiatives in the favela

Official responses to the COVID-19 crisis have been contradictory, slow, and insufficient, leading many favelas across Brazil to take things into their own hands. Local initiatives have often relied on dense, pre-existing networks of social organisations, collectives, and projects.

Some focus on raising awareness and fighting the spread of fake news. Loudspeakers, banners, and signs reinforce the message that residents should, as best as they can, follow the World Health Organization guidelines. Online, social media initiatives such as Favelas Contra o Coronavirus disseminate the latest information about the virus, its spread, and how to prevent it. Meanwhile, crowdfunding websites like the one organised by the national civil society network Central Única das Favelas (CUFA, see video below) have been able to finance a variety of local projects.

In Rio’s Complexo da Maré, meanwhile, the community NGO Redes da Maré has organised the distribution of food baskets and hygiene kits with items purchased from local shops; this effort simultaneously addresses people’s immediate needs and the survival of local businesses. In Paraisópolis, in São Paulo, the neighbourhood association has used its own initiative and a crowdfunding campaign to hire three ambulances, distribute free meals to the homeless, and create a decentralised network that monitors the wellbeing of over 100,000 residents. This new structure was implemented both to contain the spread of the virus and to locate those who are most vulnerable to sharp losses in income.

Between making ends meet, entrepreneurship, and strong grassroots organisations, favela residents continue to demonstrate their capacity to forge strong alliances and find creative solutions to deadly circumstances that just weeks ago seemed inconceivable. That said, their actions cannot and should not have to make up for decades of state negligence and poorly planned, unsustainable interventions.

Resilience is often required from those who are not able to enjoy even basic citizenship, let alone full human rights. But surviving the pandemic is not a matter of patience and painstaking dedication from those “who never asked for anything”. The inequalities and issues exposed by the pandemic have long been present and will not disappear as a result of the measures recently adopted by the government.

The momentum generated by increased awareness of such inequalities, however, might serve as a strong push towards substantive change. Guaranteeing better and stable income, as well as higher living standards for favela residents, is not only important during COVID-19. It is an issue of basic social justice and a vitally important goal in and of itself.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This article is part of an ongoing project entitled ‘Engineering Food: infrastructure exclusion and ‘last mile’ delivery in Brazilian favelas’, which is funded by The British Academy under its Urban Infrastructure and Well-Being programme.

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting