The Chilean electoral reform in 2015 is having an impact on people’s choices after decades of stagnation. This new behaviour is bringing a wider representation of its citizenship, explains Isaac Hale (UC Santa Barbara).

Lea este artículo en español

Chilean politics are in a state of upheaval. In 2019 and 2020, the country was rocked by massive demonstrations against Chile’s high levels of economic inequality. These protests led to Chile’s historic vote in 2020 to reform the country’s constitution – whose design was heavily influenced by the outgoing Augusto Pinochet dictatorship. Now, in the upcoming first round of its presidential election on November 21, it seems likely that neither of the two candidates who will advance to the second round will come from the country’s long-ruling centre-left and right electoral coalitions.

Despite the uncertainty about Chile’s political future, the country’s most recent experiment with serious institutional reform was a major success. In 2015, Chile enacted a major overhaul of its electoral system that made its legislative elections significantly more proportional. This reform was a goal of the then-governing centre-left coalition, the Nueva Mayoría, whose smaller constituent parties had long demanded changes that would allow them to compete and win seats in more districts.

The effects were dramatic in the first legislative election following the reform in 2017. As a result of the increased proportionality of the electoral system, the number of legislators from non-traditional parties rose from 3 to 17 per cent. The share of seats held by women drastically increased in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate also rose sharply, thanks to newly instituted gender quotas for party lists. In short, the Chilean legislature looked more like the Chilean public than ever before.

In a new article published in Representation, I seek to determine what Chile’s electoral reform meant for voters. Prior to reform, all Chilean legislative elections were held in two-member districts, which yielded disproportionate representation, exaggerated the electoral strength of right-wing parties, and forced smaller parties to participate in the dominant centre-left and right electoral coalitions (or be denied representation altogether). Following reform, all Chamber districts increased in size to be between three and eight seats and Senate districts between two and five. This change allows for a limited ‘natural experiment’. Given the increase in the number of seats per district in every district for the Chamber, we should expect a large decrease in strategic voting, the phenomenon whereby voters cast a vote for a candidate who is not their first choice.

Why strategic voting happens

Why does strategic voting happen more frequently in less proportional electoral systems? The reasons for this tendency are two-fold. First, there is a ‘mechanical effect’, whereby smaller parties are systematically underrepresented in the legislature by dint of the electoral system.

Another factor is psychological, as voters will be averse to ‘wasting’ their votes on parties who are unlikely to emerge victorious in their electoral district. This second effect leads to ‘instrumental’ strategic voting, where electors vote for a candidate other than their most preferred in order to reduce the odds of a less-liked candidate winning the seat. As the electoral system becomes more proportional, votes are less likely to be wasted on candidates/parties who will not earn a seat. This in turn decreases both the mechanical and psychological motivations for strategic voting.

To test whether Chile’s electoral reform decreased strategic voting I employ data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES). These combined Chilean election studies include survey responses from 4,800 voters in the 2005, 2009, and 2017 general elections. Using these large-N voter-level data, I construct a logistic regression where I predict the probability of a voter casting a ‘strategic’ vote for a party other than their most-preferred in their district’s Chamber election. The primary explanatory variable is the district magnitude for the voter’s Chamber district. I also include control variables for education and election year.

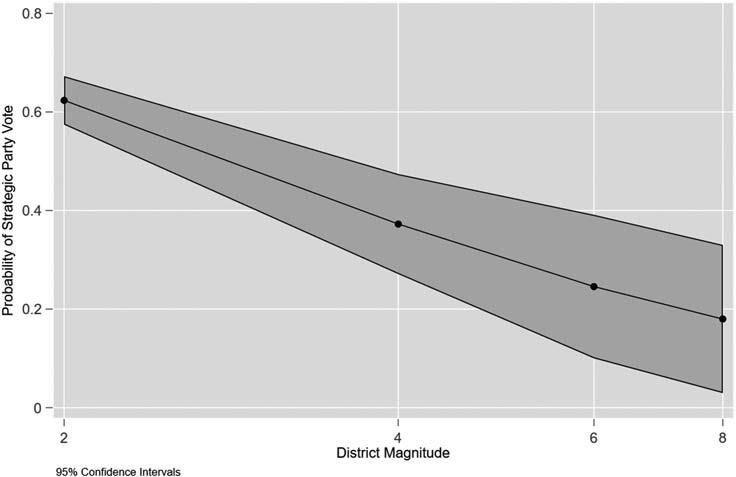

The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 1 below. The Y-axis in Figure 1 corresponds to the probability of a voter casting a strategic vote for a party other than their most preferred. The X-axis is the district magnitude, ranging from two (as in all pre-reform districts) to a maximum of eight. The shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals.

Electoral reform had a strong negative effect on strategic voting. As district magnitude increases post-reform, the likelihood of the voter casting a strategic vote decreases. In two-seat districts, the likelihood of a strategic vote is over 60%, but in eight-seat districts the odds of a strategic vote are less than 20%. Even a moderate growth in district magnitude from two to four corresponds with a decrease in the likelihood of strategic voting of more than 20%.

While strategic voting in the Chilean electorate is clearly affected by the increased district magnitude brought on by electoral reform, it is important to note that the effect is not uniform across partisan groups.

A wider representation of Chileans

The fragmentation of the Chilean party system is broad, but it has always been greater on the centre and left. While many of these parties had stark ideological differences (such as those between the Christian Democrats and the Communists), the parties frequently ran in electoral coalitions together due to the incentives created by the pre-reform electoral system. Because coalitions could only nominate two candidates per district, the main centre-left coalition (initially called the Concertación) could only run candidates from a sub-set of its constituent parties in each district. By contrast, the post-dictatorship right-wing coalition (initially called Democracia y Progreso) has largely consisted of only two parties (UDI and RN), meaning that they had the option of running one candidate from each party in most districts. As such, the effect of electoral reform on strategic party voting is concentrated on voters who identify with centre and left parties.

Chile’s electoral reform is having an immediate impact on the country’s elections. Not only is the number of parties in the legislature growing after two decades of stagnation, but voters are increasingly voting sincerely for their most-preferred party. The 2015 reform had a broad and ambitious list of goals, including increasing the representation of women via gender quotas, increasing the competitiveness of elections, and easing the difficulty of intra-coalition bargaining between allied parties, and reducing the malapportionment of Chamber districts. While not every goal has been met (districts are still malapportioned), the evidence provided in my research suggests that voters, especially those in the most proportional districts, are already modifying their behavior in response to the new electoral system. Though the history of Chile’s electoral coalitions makes this effect less pronounced among supporters of right-wing parties, the impact on the majority of voters who typically support centre or left parties is notable.

Strategic voting poses normative challenges for representation. A decrease in strategic voting means that voters’ sincere ideological preferences are better represented in the legislature. This positive change complements the already-known benefits of Chile’s 2015 reform, including more diverse party representation and improved representation of women.

Though Chile’s Constitutional Convention could propose an entirely new electoral system (or more minor electoral reforms) in the coming months, the 2015 reforms were a success. Increasing district magnitude not only yields more proportional representation but also decreases strategic voting. Activists and reformers would be well-served to consider Chile’s example when proposing changes to their own country’s electoral systems.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting