Costa Rica held a national election on February 6 that will head to a runoff between two seriously questioned candidates, José María Figueres and Rodrigo Chaves. This campaign will turn unpredictable, and the vote mobilisation will be limited, Ilka Treminio (University of Costa Rica) argues.

Lee este post en español

A total of 25 political parties participated in the Costa Rica presidential elections on February 6. This is the highest number of contestants in Costa Rica’s democratic history. Still, since no candidacy reached the threshold of 40% of the valid votes required to win in the first electoral round, the country will hold a runoff election on April 3. That atypically large time gap between elections means that a new and decisive campaign starts again.

Ideologically, most parties were distributed from the centre to the right, and among the parties that stood out in voting intention, only the Broad Front (Frente Amplio) identified itself as centre-left. Except for those on the left, contenders championed reducing the state apparatus, defending a macroeconomic austerity policy, and anti-progressive attitudes on women’s rights. This last issue has been paramount given the accusations of sexual harassment against candidate Rodrigo Chaves. Further issues like the use of renewable energies vs oil exploration showed more pragmatic than ideological positions; it was difficult to know the value background of the main political forces.

The fourth wave of Covid-19, caused by the omicron variant, did not allow the normal development of face-to-face political events. Moreover, for the first time, the pressure of public opinion on legislative activity prevented deputies from extending their vacations during January to support the campaigns of their political parties. This reduced their power in their territories, and for these reasons, voter mobilisation was weaker than usual.

This campaign barely discussed drug trafficking in the political sphere or corruption in allocating public contracts for infrastructure works. Neither did it address the need to strengthen health care systems, which was vital in managing the pandemic. This lack of conversation was due to the dispersion and separation of political agendas, among other reasons.

On this occasion, the electorate had few resources to decide their vote. On the one hand, most of the candidates came from new and disjointed parties. On the other, that wide partisan offer did not allow in-depth knowledge of each contender’s ideas. Moreover, Costa Rica doesn’t offer free advertising slots in media, meaning that not all the parties can advertise and appear in mainstream outlets.

In addition, campaigns did not offer an adequate differentiation. Instead, they leaned in an artificial moderation. The clearest example was that of the evangelical candidate Fabricio Alvarado. He ran for the 2018 election with an openly polarising platform but on this occasion presented himself as a moderate option with a more technical economic approach. He possibly intended to capture centre voters to ensure a potential victory in the runoff. Although Alvarado came close to passing the first round, his party ended up in third place and did not make it to the runoff. However, according to preliminary counts, he secured a seat in the Legislative Assembly along with six other members of his party.

Undecided vote and other challenges to predicting a final result

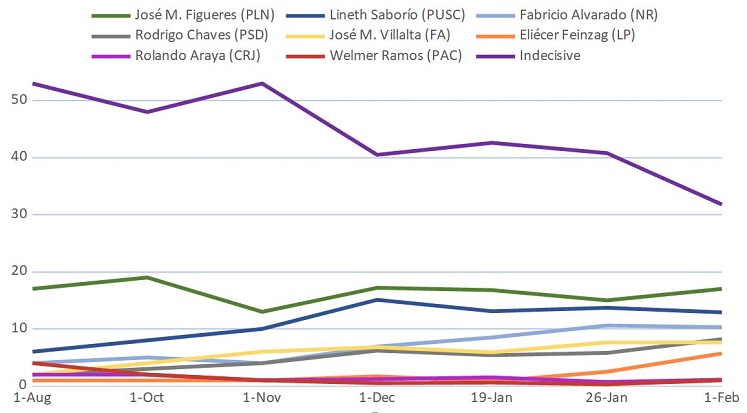

Two features stand out when observing the voting intention data. First, there was a high percentage of undecided voters. Second, the concentration of preferences among the six main political options, with slight percentage differences between them, made it impossible to predict the poll’s results.

That extensive registration of parties came along with a figure allowed by the Costa Rican law called “double nomination”. It means that the presidential candidates can also register on top of the list of the legislative ballot. 17 parties out of 25 did it, with various actors warning of the possibility of a high level of legislative fragmentation and the increase in single-person fractions. However, only two candidates with double nominations reached the newly elected Assembly: Eliécer Feinzaig of the Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) and the aforementioned Fabricio Alvarado of Nueva República (NR). Paradoxically, this election reduced the number of legislative representation from 7 in 2018 to 6 in 2022.

Former president José María Figueres (1994-1998) of the National Liberation party (PLN) won the first round. He will dispute the runoff against Rodrigo Chaves and his newbie Progress Social Democratic Party (PSD). Chaves is an economist who was the World Bank’s Country Director for Indonesia and was a finance minister of Costa Rica for a short period in the outgoing government. He was appointed in 2019 after he resigned from the World Bank in response to “relentless and unwanted advances” towards six women, according to the bank’s tribunal, the Wall Street Journal reported.

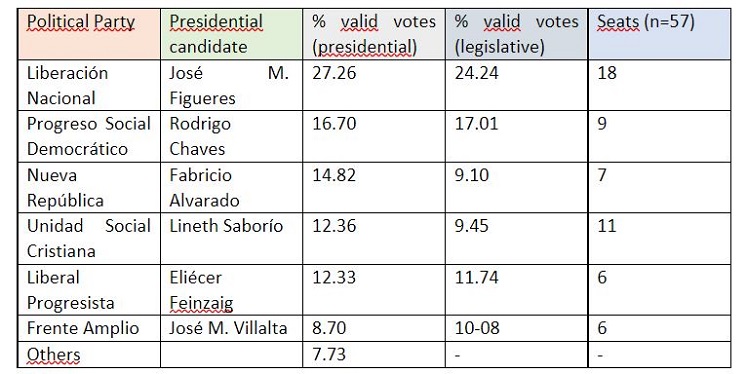

This vote turnout (59.71%) is the lowest in Costa Rica’s recent history and seriously worries analysts since it has deepened the trend towards abstentionism. With 90% of the polling stations counted, the official results of the elections are as follows:

The Citizens’ Action Party (PAC) has been in power for two terms (2014 – 2022). Still, it was left out of the Legislative Assembly and its candidate, Welmer Ramos, got only 0.66% of the votes for the presidential election. These results leave the ruling party severely weakened because it did not get seats, and it will not have access to public funding, and they depend on it to pay the debt after two members of PAC were found guilty of fraud in their public campaign financing in 2010. At the same time, this defeat leaves a void in the parliament’s ideological distribution since the Broad Front is the only progressive party that will have representation in it with six seats. Although José María Figueres’ National Liberation (PLN) includes some welfare-type social policies such as the minimum wage for people in extreme poverty and conditional cash transfers in its manifesto, the other four parties in the Assembly have conservative agendas.

Finally, the voter’s mobilisation will be limited in the runoff because the ballot has two seriously questioned candidates. José María Figueres is under scrutiny for acts of corruption during his first presidential term, and Rodrigo Chaves for cases of sexual harassment in the World Bank. Figueres has the largest number of legislators after this first round. If he wins and makes a coalition with the conservatives Social Christian Unity (PSUC), the second party in the chamber, they could reach an absolute majority of 29 votes. Something highly plausible since both parties have followed the traditional bipartisan government formula in the past. However, if Rodrigo Chaves wins, he will find himself in a more complex situation. He has the third-largest number of seats and would have to make an enormous effort to free himself from the vetoes of a majoritarian opposition. Citizens will hardly be encouraged to participate in this scenario, although the campaign’s final stretch is currently unpredictable.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

• Banner image: Luis Alvarado Alvarado / Shutterstock

Me parece este análisis de la panorama política muy claro y bien al fondo de la situación actual en tico. En mi criterio la razón más clave de la fractura socio económico en el mundo hoy día es la desconexión de los seres con el ambiente natural, tanto por fuera como adentro de nosotros.

Slow down and take stock, sister and brother 🙂