Ideology is not always enough to predict trust in the armed forces, and potentially in other institutions. Over time, elites have changed their views towards the military and the evolution of trust varies. Countries that have had moderate left-wing parties in power have narrowed the ideological gap in terms of trust in the armed forces, found Cristian Márquez Romo (Universidad de Salamanca) and Xavier Romero Vidal (University of Cambridge).

In November 2019, the head of the Bolivian armed forces, Williams Kaliman, urged President Evo Morales to resign. The mobilisations after the election in which Morales was seeking re-election for the fourth time and military intervention led to the resignation and exile of the Bolivian president. There are other examples of military interventions in political processes in Latin America in the last decade, like Venezuela (2002), Honduras (2009) and Ecuador (2010). As Larry Diamond pointed out, militarism has persisted in Latin America even after the third wave of democratisation (1974-1990). More than thirty countries in Europe, East Asia, and Latin America shifted from authoritarian to democratic governments in that period.

Before the democratic transitions, the Latin American left was severely repressed by successive military regimes. Throughout the 20th century, left-wing governments had conflictive relations with the military, most of which ended in coups d’état. By the beginning of the 21st century, the historical tension between the left and the army was dramatically transformed when a wave of new left-leaning governments came to office. In this period, known as the left-turn, left-wing parties and the armed forces found spaces of convergence of interests.

As Jorge Battaglino argues, such convergence of interests enabled the coming to power of new left-leaning governments, which would have triggered significant political instability at other points in time. Understanding this process of convergence of interests is of great relevance for the future of democracy in the region. Yet, the literature has instead focused on the consequences of this left-turn on party systems, or the greater or lesser moderation of left-leaning governments during this process. Research on public trust in the armed forces has focused on analysing individual-level variables, showing that conservative citizens tend to trust more and evaluate the military better.

In a recent article, we analysed the link between political ideology and trust in the military in 18 Latin American countries. We wanted to explore the relationship between the left and the army. To do it, we used data from the Americas Barometer of the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) and the Latin American Elites project of the University of Salamanca (PELA-USAL), which has regularly surveyed Latin America’s members of parliament since 1994.

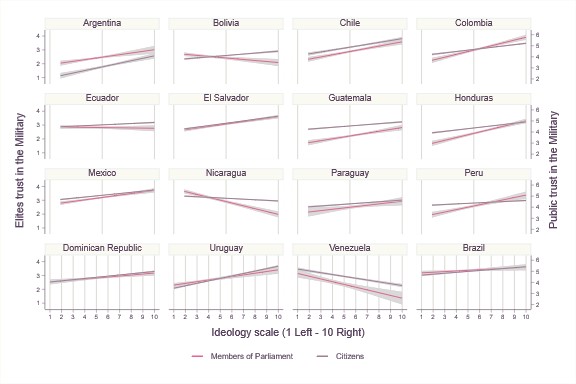

Citizens on the right of the ideological spectrum tend to trust the military more in most countries. Interestingly, this relationship is reversed in some countries. In Venezuela and Nicaragua, citizens on the left show, on average, greater trust in the armed forces than those on the right. Among elites, and in line with the general trend among the public, right-wing parliamentarians tend to have more confidence in the armed forces than those on the left in most countries. Again, this relationship is reversed in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia: left-wing parliamentarians have significantly more confidence in their armed forces than right-wing parliamentarians.

Figure 1 illustrates the average trust of citizens and parliamentary elites according to their ideological self-placement on the left-right axis in each country from 2004-to 2019.

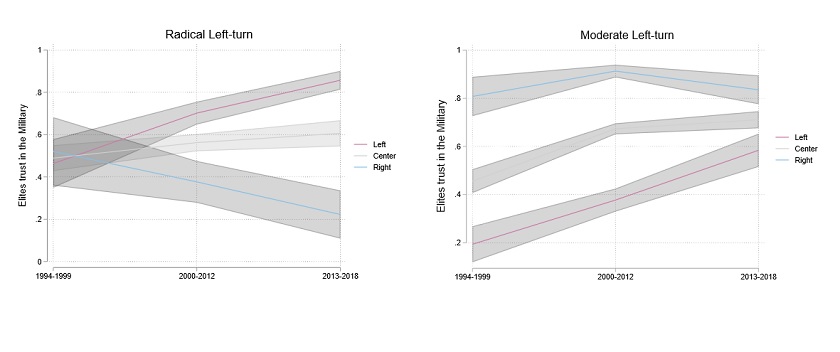

Why does ideology have the opposite relationship with trust in the armed forces in these countries? To explain the left-turn role in that connection, we scrutinised the evolution of trust in the military across ideological groups over time. There are important differences between the left governments elected during Latin America’s turn to the left. In particular, and following the distinction between moderate and radical leftism (Weyland, 2010; Weyland, Madrid y Hunter, 2010; Panizza, 2005), we analyse the evolution of trust in the military among the elites of the two groups of countries that were part of this political cycle. We divided it into those in which a moderate left, such as Michelle Bachelet’s in Chile governed, and those in which a radical left came to power, such as Hugo Chávez in Venezuela.

Ideology isn’t enough to predict trust in the armed forces

In countries where a relatively moderate left-wing party came to power, such as Brazil, Chile or Uruguay, we found a process of ideological convergence towards trust in the military. The left’s increased reliance on this institution generated convergence, where the ideological gap in trust in the military narrowed. In contrast, where the shift to the left brought a radical left to power, ideological polarisation around the armed forces was triggered.

While left-wing elites in Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua and Ecuador significantly increased their confidence in the military, right-wing elites drastically reduced their confidence in this institution. Up to the point of reversing the international trend that associates ideological conservatism with greater confidence in the armed forces.

Our study reveals that ideology (both among parliamentary elites and citizens) is not always enough to predict trust in the army and potentially in other institutions. The political and historical context is vital to understanding individual attitudes and incorporating trends over time. A left resurgence in the region provoked opposing national dynamics vis-à-vis the armed forces: Convergence when moderate left-leaning governments came to power and polarisation when the radical left did.

Experts suggest that one of the main threats that challenge democratic governments in Latin America is that unelected actors, such as the military, can seize power from elected officials. We identified the historical trends that reveal opposing associations between ideology and political elites’ (miss)trust in the armed forces. These allegiances are crucial to understanding the changes in civil-military relations better, and thus the potential role of the armed forces in critical junctures of political instability in the region.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the author rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

• Banner image: Great Military Parade of Chile, 2021/ Ejército de Chile (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)