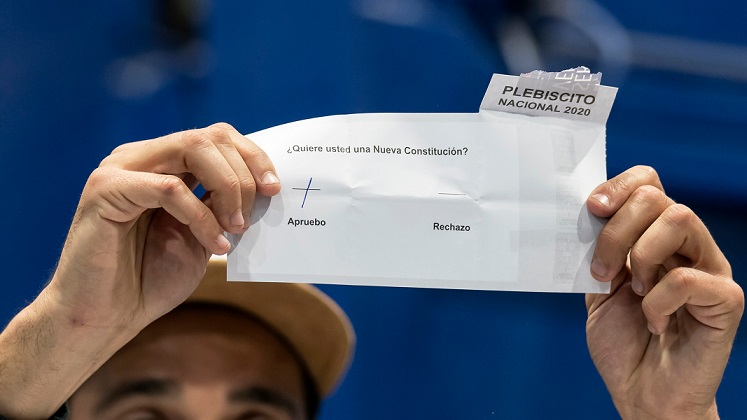

On 4 September, Chile voted to reject a new constitution to replace the current one, which was written under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. Although 78% of voters approved changing the constitution in a referendum in 2020, the plebiscite in 2022 faced a significant rejection. After that turmoil, the country needs to address the need for cultural transformation, María Carrasco (Atlantic Fellow for Social and Economic Equity, LSE) argues.

The people that voted to approve the new constitution on the plebiscite on 4 September, including myself, feel disappointed, hopeless, and incredibly shocked. The result was astonishing, as in the previous decade, it seemed like the tide was changing in Chile and that people wanted change.

We have witnessed social movements leading to a paradigm shift in education, environmental movements stopping the approval of a controversial hydroelectric megaproject, and feminist movements leading to the passing of a bill on the legalisation of abortion. Even the original referendum on whether a new constitution should be written was approved by almost 80% of the electorate in October 2020. So, why did Chileans reject the new constitution despite all of this?

The plausible reasons

How can a country that approved writing a new constitution with a 78.27% majority now reject it with a 61.86% majority? Some possible reasons why Chileans rejected the constitution are the progressive aspect of the text, where plurinationality was particularly controversial; the national convention’s lack of capacity to include the right-wing in the negotiation and definition of the rights; lack of legitimacy due to problematic behaviour of some convention member, including lying about having cancer to get elected; the ambiguity of the text and its complexity; and a division among the centre-left on whether to approve or reject the new constitution (Molina P. , 2020).

In addition, several obstacles made it harder for voters to understand and learn about the constitutional content. For example, fake news and disinformation were shared on social media ahead of the vote. So much so that even a member of the U.S Congress called attention to the problem on his social media channels. Another obstacle was the uneven access to resources between the two campaigns, where 89% of all private donations were given to the rejection campaign and only 11% to the approval campaign.

The emergence of new voters

Even considering all the plausible reasons, the difference between the two votes was still astonishing. So, what explains the shift?

The data below shows that a new group of voters emerged in the second voting. For the first time in the history of Chile, all citizens were automatically registered to vote, as voting was compulsory. This resulted in the highest voter turnout in recent history, reaching 85.82%. The same analysis shows a substantial increase in voter turnout in all regions, especially in the north and the south of the country. In fact, following the analysis of NGO Decide Chile, more than 4.8 million people voted this time that hadn’t voted in the previous elections.

Data also shows that almost the same number of people voted for the current progressive left-wing president in 2021 as for approving the new constitution. Even more, the conventional member’s election turnout was only 43.35%, while the last referendum turnout was 85.3%, representing an over 100% increase. These numbers show the huge impact that the group of new voters had on the voting. In the end, the 55.6% increase in voter turnout determined the referendum result.

A country with contradictions: confronting values

In an interview before the vote, a convention member, regarding the question about what a new convention should look like if the reject option won, answered that there was nothing more representative of what Chilean society is than the constitutional convention. He said, “the convention was the expression of the permanent tensions of Chile….” (Baranda, 2020). And yes, for the first time in our history, the story was written with people outside of the traditional political sphere and an array of social sectors and minority groups in mind (Rios, 2021; Universidad de Valparaíso, 2021).

Ultimately, by rejecting the new constitution, we have rejected the social and political values proposed by the convention. We have rejected the notions of social rights, the right for nature to be protected, sexual and reproductive rights, and the right for indigenous communities to be listened to when the state or the society is harming their rights, among others. However, we have not just rejected rights. We have also rejected the values of that part of the society divided by inequality and injustice, and we have rejected one of the most representative political bodies in our history.

If the convention was highly representative of our society, why was its constitution draft rejected? Because there is a permanent tension embedded in our community as the sharp inequality divides us. The upper-income class can access worldwide education, health, and transport services, while the low-income families have access to public services similar to those in the world’s poorest countries. But the difference is also about values.

The progressive side of our society co-exists with a conservative camp where the existing order is considered important in regulating our coexistence. The last survey of the Center for Public Studies indicates an increase in the importance of values such as public security and individual effort-reward (CEP Chile, 2022). These are essential values of Chilean society. Whereas solidarity, as the main principle of the new constitution, seems not to be wanted nor needed to overcome the well-being inequalities in our country.

So, yes, we have failed as a society because, after so many years of social protests and movements, we still have not realised that we haven’t truly changed our values and mindset. The proposed constitution seemed to have been pitched for the Chile we want to see and not for the Chile that we currently have. After the pandemic, we are even more unequal than before. Yet, we have not problematized that the state and society have much to say about solving our problems based on solidarity. The pandemic exemplifies how much we need to collaborate to solve complex issues.

I cannot stop thinking about Pepe Mujica’s sentence in his documentary, “the most important transformation is not political, but cultural.” We failed to approve the new constitution because we haven’t addressed the need for a cultural transformation that would allow us to negotiate a new set of values with one another. The proposed new constitution was based on values such as solidarity, ecocentrism, probity, good governance, and territorial autonomy, which seem far from something that the majority of voters could agree on.

While we are not going to have a new constitution created by one of the most representative bodies in our democratic history, and with the highest level of transparency, hopefully, in the future, we will be able to evolve and transform culturally as a society, leading to a political change, and not the other way around.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This article post was first published on the Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity blog

• Please read our comments policy before commenting

• Banner image: A woman counts a vote in the Chilean plebiscite in September 2022 / Klopping (Shutterstock)

I am currently writing some reflections about a similar topic, which led me to this blog. I consider my self, or at least try to be, respectful of others ideas and open to reflect. But sorry, I could just not avoid to make this comment. I am just surprised about the level of the analysis. I would have never expected it from a LSE Fellow. Also, the superior morality, let´s say, for instance about conservative farmers and peasants communities. Or, that because Chile rejected this proposal, it automatically meant to reject all the values aboved mentioned. Furthermore, it is true: never in Chile´s history indigeneous people had so much participation in a policy process. Yet, the blindness to realize that in all indigeneous county´s the rejection option won. So, can we really talk about that they were represented? With that level of analysis and scholars´ disconnection from common the left won´t be able to construct a project that is embraced by people. Rather, it will continue to pave the way to what we are witnessing today with the rise of the extreme right wing in Chile. Perhaps, better than framing the issue as “confronting values” -between who? Me the progressive that has the reason and cares for natures and women rights versus ignorant conservative huasos that torture animals in rodeo- I invite to see best filmaker in Chile´s history: Raul Ruiz. Specially, between thr 1964 – 1975 period, to change the framing from “confrontation” to the “contradictions innner to each of us”.