The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted education in Latin America, with school closures leading to significant setbacks in inequality and poverty. In an upcoming article for the journal Economía, Nora Lustig (Tulane University), Valentina Martínez Pabón (Yale University), Guido Neidhöfer (ZEW Mannheim), and Mariano Tommasi (Universidad de San Andrés) explore the challenges in social mobility and equality in the region after the recent educational gap.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented challenges to Latin America, with devastating effects on health and the economy. During 2020, the region was one of the hardest hit, with several countries topping the lists of infected and dead, along with GDP decreasing by 7%. Although the worst of the health crisis has passed and economic recovery is underway, the pandemic triggered significant lingering setbacks in inequality and poverty. While the economic growth may reverse these, there are effects with consequences that will be long-lasting unless strong actions are undertaken to mitigate them. Education is one of the various channels that the COVID shock will impact the future, and more worringly, is one of the most important. The impact of school closures on school achievements for children of different socioeconomic backgrounds stands out. School closures affected the children of low-income households because they found it extremely difficult to continue their education at home due to a lack of adequate equipment, connectivity, and mentoring. The long-term effects of the pandemic on education inequality could be profound, potentially widening the gap between the haves and have-nots and reducing intergenerational mobility in a significant way.

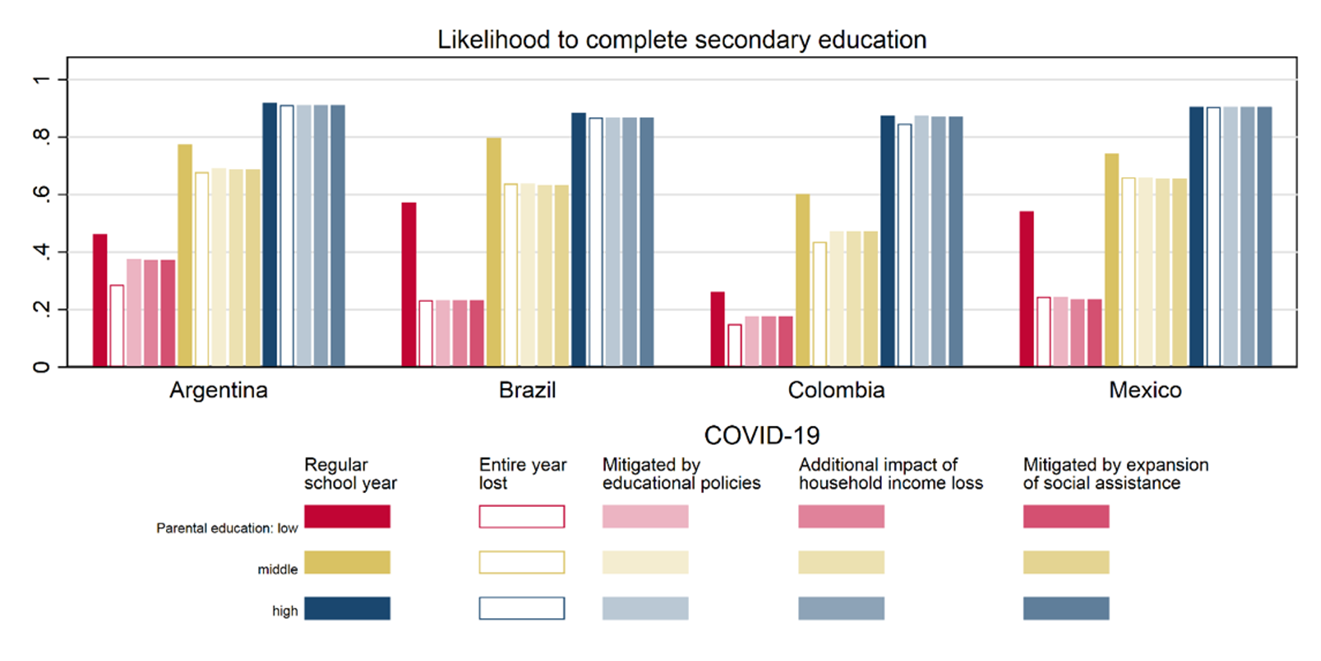

To estimate the potential impact of the pandemic on school achievements and their persistence, we simulated the probability of completing secondary school for children from different socioeconomic backgrounds in the four largest Latin American countries: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. We used information regarding school closures and educational mitigation policies. We also accounted for educational losses related to health shocks and parental job loss. Instructional loss was quite different for children from disadvantaged households. In Argentina, the lost days represented 23% of the school year for children whose parents had not completed secondary school, while it was only 3% for children whose parents had more than secondary education. Colombia’s numbers were 28% vs 2%. In Brazil and Mexico, the contrast was more striking: 42% vs 5% and 54% vs 7%, respectively.

We found that for children whose parents are in the bottom tercile of educational background, the probability of completing high school could decline from a pre-pandemic level of 46.2% to 37.7% in Argentina, from 57.3% to 23.2% in Brazil, from 26.2% to 17.7% in Colombia, and from 54.2% to 24.5% in Mexico. In contrast, the pandemic would barely affect those children whose parents are in the top tercile of educational background, (see Figure 1). In some of the poorer countries in the region, the impact is even more drastic. In Guatemala and Honduras, the probability of secondary school completion of individuals from lower-educated families might even fall below 10% (Neidhöfer, Lustig, and Tommasi, 2021). For the Latin American region, this reduction erases half a century of progress in school completion rates for the affected generation.

A gap that may damage social mobility and equality

One of the factors underlying these results is the digital divide. Students living in rural areas and from low-income households had limited access to technology and internet services. For instance, when the pandemic hit, the internet coverage in households whose head had less than primary education was around 33% in Colombia and Mexico, 49% in Brazil, and 63% in Argentina. In contrast, coverage was around 90% for households whose head had more than secondary education (see Table 5 in Lustig et al., forthcoming). Beyond the lack of access to the internet and technology, school closures disrupted the learning process and the lack of social interaction and support from teachers and peers. This could have also affected mental health and non-cognitive skills, which may have compounded the negative impact of the shock.

The growing educational gap will damage social mobility and equality of opportunity for years to come unless we take the warning signs seriously and act fast. There is a need to compensate for the losses by increasing both the amount and quality of learning time. School systems must contemplate extended schedules, summer and after-school programs, and more personalised instruction. Efforts should also be geared toward developing online and offline resources available for free and expanding connectivity.

Particular attention should be placed on the socioemotional needs of vulnerable children at risk of school dropout. These actions will require resources, especially financial. We recommend governments to not cut education spending when facing the inevitable need to reign in fiscal deficits, which were acceptable during the pandemic. If anything, fiscal resources devoted to education may need to rise. The challenge is so daunting that help will be needed from non-state actors as well, such as private philanthropy, the for-profit sector, and community-based organisations.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This post is based on Nora Lustig, Valentina Martínez Pabón, Guido Neidhöfer, and Mariano Tommasi. “Short and Long-Run Distributional Impacts of COVID-19 in Latin America.” Forthcoming in Economía.

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

• Banner image: Murales pintados por profesores y estudiantes del Colegio de Bachilleres No. 28 en San Luis Potosí, México / Lucy Nieto (CC BY-NC 2.0)