In this article, Joss Harrison explores the expansion of the U.S. base system in the Indian Ocean under the Carter administration. The binary focus on Indian-Chinese competition in the Indian Ocean neglects the enduring American base footprint in the region. The Carter administration developed the U.S. presence in the Indian Ocean due to a combination of endogenous and exogenous factors.

INTRODUCTION

A narrative has emerged in recent years of a developing competition for military bases between China and India in the Indian Ocean region. For example, Indian Ocean security expert David Brewster argues that “The jostling for influence in [the eastern Indian Ocean] between China and India is already highly reminiscent of U.S.-Soviet competition for influence during the Cold War.”[1] Asia strategy expert Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, similarly, emphasises India-China competition in South Asia.[2] China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017, and India has been accused of seeking to construct a base on Mauritius’ Agaléga Island. [3] However, a binary focus on India-China competition in the Indian Ocean neglects the enduring American base footprint in a region half the world away from its own shores. In this article, I place the American military footprint in the Indian Ocean region in its historical context region by analysing archival documents from the Jimmy Carter administration. The article will demonstrate that the Carter administration, in response both to external crises and internal dynamics, laid the groundwork for the U.S.’ enduring position in the region today.

WHAT ARE MILITARY BASES?

Applying the term ‘military base’ poses certain challenges, not least because states go to great rhetorical lengths not to utter it. The standard euphemism for an overseas military base is ‘facility’, an innocent term that succeeds in its objective of conjuring no imagery at all. Overseas bases permit a state’s military to operate from land outside its mainland borders.[4] Their function is to facilitate power projection – “the ability to transport overwhelming air, sea and land power to far-off places” – and to increase the practical reach of the state.[5]

A BRIEF HISTORY OF U.S. BASE POLICY

Military bases are central to U.S. foreign/imperial policy. Whereas European empires in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries exercised global influence by colonising and directly controlling huge swathes of territory, the American empire relies on a worldwide network of bases that enables it to project its military power into practically any region of the world at short notice.[6] The U.S. has competed for international bases since the 1870s, when President Ulysses S. Grant unsuccessfully attempted to annex the Dominican Republic, hoping to establish a new base for the U.S. Navy.[7] In 1890, naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan published The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, which argued that the U.S. should establish bases in Hawaii, the Caribbean, and the Philippines to extend its naval power and protect its commerce.[8] The book made waves in the U.S. foreign policy establishment; Theodore Roosevelt himself commented that “I am greatly in error if it does not become a naval classic”.[9] By 1902, the U.S. had annexed Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines, and had established indirect rule over Cuba. Although the U.S. later relinquished control over the Philippines and Cuba, it accumulated a global network of bases during the Second World War and Cold War, which number around 800 today.[10]

ENTER JIMMY CARTER

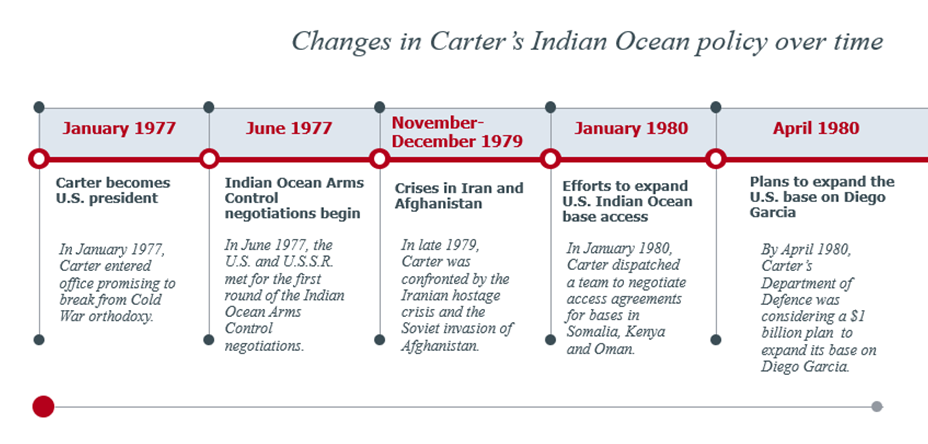

The U.S. president most directly responsible for escalating the U.S.’ base footprint in the Indian Ocean region was Jimmy Carter. There is a certain irony in this. Carter entered the Oval Office in 1977 promising to break from Cold War orthodoxy.[11] In his first year in office, he initiated negotiations with the Soviet Union to demilitarise the Indian Ocean, with the aspiration of achieving “some retrogression in military force presence.” [12] Neither superpower had an especially extensive military presence in the region at the time, though the U.S.’ position was stronger than that of the Soviet Union.[13] This, according to U.S. officials, owed principally to the fact that they had a “politically secure” and permanent base on Diego Garcia (a sanitised way of acknowledging that the island’s population had been forcibly evicted, thus precluding any local anti-imperial resistance).[14] The Soviet Union, by contrast, depended on a base leased from the Somalian government at Berbera, to which their access could be withdrawn at any time.[15] By the end of his presidency, Carter had completely reversed his original stance, moving to significantly expand the U.S.’ base footprint in the Indian Ocean region.

The most commonly attributed causes of this volte-face are the twin crises that Carter faced at the end of 1979: the Iranian hostage crisis, which started on 4 November, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which commenced on 24 December. These crises, it is argued, led Carter to abandon the idealistic elements of his foreign policy and turn towards a hard-nosed realist approach.[16]

Timeline, courtesy of the author

Without question, these twin crises did provide a significant impetus for U.S. base expansion in the Indian Ocean region. This is evident from deliberations within the administration in their immediate aftermath. At a November 8 meeting of the Special Coordination Committee, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) recommended using the American base on Diego Garcia, an atoll in the Chagos Archipelago coercively separated from Mauritius by the UK and the U.S. in 1965, to launch an AC-130 gunship attack on Iranian oil refineries in the event that the hostages were harmed.[17] On 20 November, at a meeting of the National Security Council, Carter also decided to enhance the refuelling capability of the base on Diego Garcia, which was already being considered for use in a prospective rescue mission.[18] This contradicted the U.S.’ public insistence that Diego Garcia was merely a ‘communications facility’. It also represented a stark reversal of Carter’s willingness in 1977 to consider relinquishing Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean Arms Control negotiations; he had felt then that the base was “of minimal strategic importance.” [19]

Additionally, the Carter administration began to search proactively for new bases on the Indian Ocean littoral. In his January 1980 State of the Union address, Carter credited his administration with “making arrangements for key naval and air facilities to be used by our forces in the region of northeast Africa and the Persian Gulf.” [20] As early as December 1979, Carter rebuked his national security team for not moving fast enough to secure bases in Somalia, Kenya and Oman, which had been identified as potential hosts.[21] In January 1980, the administration despatched a team to start negotiating access agreements with these states. By September 1980, the administration had signed access agreements with Somalia, Kenya and Oman to use military bases in their territory and had an agreement in principle with Egypt for the same purpose.[22] Thus, in the space of a year, Carter had utterly transformed the U.S.’ military footprint in the Indian Ocean region.

However, the Carter administration’s decision to militarise the Indian Ocean region was also the product of endogenous dynamics. Long before the Iranian hostage crisis or the invasion of Afghanistan, the Department of Defence (DOD) and JCS had quietly laid the groundwork for an augmented U.S. presence in the region. Crucially, they succeeded in obstructing Carter’s Indian Ocean Arms Control negotiations, advancing a novel interpretation of ‘demilitarisation’ in which both sides would merely commit to preserving the status quo.[23] They also insisted that under the terms of the freeze, the U.S. would be permitted to complete an ongoing expansion of its base on Diego Garcia.[24] In September 1977, Carter capitulated to these demands.[25] This, as the DOD and JCS gleefully acknowledged, meant locking in a balance of military force that favoured the U.S. Unsurprisingly, the Soviet Union found this to be an unappealing proposition, and the negotiations had stalled by 1979. The JCS admitted in June 1979 that they had “never been enthusiastic about the Indian Ocean Talks” so were probably not overly disappointed by this outcome.[26] Carter’s enthusiasm for the negotiations had also cooled by this point; in February 1979, he had instructed Secretary of Defence Harold Brown to sound out Middle Eastern states as to whether they would be willing to accept a greater American military presence in the region, including new bases.[27]

Furthermore, on October 25, 1979, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, Harold Brown, and National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski provisionally approved a $100 million package to further upgrade the U.S.’ base on Diego Garcia.[28] Brown had been calling for such an expansion since at least February 1979.[29] This package would upgrade Diego Garcia’s airlift and sealift capability.[30] Then, in 1980, following the twin crises, the Carter administration put forward a $1 billion plan to militarise Diego Garcia.[31] Among other enhancements, this would widen the base’s runways in order to support bomber aircraft. It is therefore evident that the U.S. project to upgrade Diego Garcia preceded, but received further impetus from, the twin crises of 1979.

CONCLUSION

Contrary to Carter’s initial intentions, his administration significantly expanded the U.S.’ military presence in the Indian Ocean region. By the time Carter left office in January 1981, the U.S. had committed to expanding its base on Diego Garcia and had signed access agreements for bases in Somalia, Kenya and Oman. This is best understood as a result of both endogenous and exogenous factors.

The legacy of Carter’s militarisation of the Indian Ocean region endures. The U.S. used its military base on Diego Garcia for bombing missions in the Gulf War, Iraq War, and Afghanistan War. More recently, in 2020, the Trump administration deployed six B-52 bombers to Diego Garcia amidst tensions with Iran.[32] This is regularly obscured in recent commentary on bases in the Indian Ocean region, which focuses on competition between India and China, while neglecting the U.S. military presence there.

Featured image: Jimmy Carter visit the Naval Academy at Annapolis, MD – NARA, taken from WIkimedia.

[1] Brewster, D., 2018. China’s play for military bases in the eastern Indian Ocean. Lowy Institute. Available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/china-s-play-military-bases-eastern-indian-ocean

[2] Rajagopalan, R.P., 2020. Sino-Indian competition in the Indian Ocean Region intensifies. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/sino-indian-competition-in-the-indian-ocean-region-intensifies/

[3] Chandran, N., 2018. Indian military scrambles to keep up after China moves to put forces in Africa. CNBC. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/02/28/military-china-and-india-compete-over-bases-around-indian-ocean.html; Thakker, A., 2018. A rising india in the Indian Ocean needs a strong Navy. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available at: https://www.csis.org/npfp/rising-india-indian-ocean-needs-strong-navy

[4] Calder, K.E., 2007. Embattled Garrisons: Comparative Base Politics and American Globalism, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 9.

[5] Mazarr, M.J., 2020. Toward a New Theory of Power Projection. War on the Rocks. Available at: https://warontherocks.com/2020/04/toward-a-new-theory-of-power-projection/

[6] Immerwahr, D., 2019. How to Hide an Empire, Vintage Publishing.

[7] Waugh, J., (2017). Ulysses S. Grant: Foreign Affairs. Miller Center. Available at: https://millercenter.org/president/grant/foreign-affairs

[8] Malan, A.T., 2004. The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783. Project Gutenberg. Available at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13529/13529-h.htm

[9] Karsten, P., 1971. The nature of “Influence”: Roosevelt, Malan and the concept of Sea Power. American Quarterly, 23(4), 589.

[10] Vine, D. Where in the world is the U.S. military? POLITICO Magazine. Available at: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/06/us-military-bases-around-the-world-119321/

[11] Schmitz, D.F. & Walker, V., 2004. Jimmy Carter and the Foreign Policy of Human Rights: The Development of a Post-Cold War Foreign Policy. Diplomatic History, 28(1), 113-143.

[12] Foreign Relations of the United States, 1977-1980, Volume XVIII, Middle East Region; Arabian Peninsula, eds. Kelly M. McFarland and Adam M. Howard (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2015), Document 106.

[13] Ibid, Document 105.

[14] Ibid, Document 100.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Gaddis, J.L., 2005. The Cold War: A New History, Penguin; Rosati, J., 1994. The Rise and Fall of America’s First Post-Cold War Foreign Policy. In H. D. Rosenbaum & A. Ugrinsky, eds. Jimmy Carter: Foreign Policy and Post-Presidential Years. Westport, CT, 44-46.

[17] Foreign Relations of the United States, 1977-1980, Volume XI, Part 1, Iran: Hostage Crisis, November 1979-September 1980, eds. Linda Qaimmaqami and Kathleen B. Rasmussen (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2020), Document 13.

[18] Ibid, Document 41.

[19] Foreign Relations of the United States, 1977-1980, Volume XVIII, Middle East Region; Arabian Peninsula, eds. Kelly M. McFarland and Adam M. Howard (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2015), Document 106.

[20] Carter, J., 1980. State of the Union Address 1980. Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum. Available at: https://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/assets/documents/speeches/su80jec.phtml

[21] Foreign Relations of the United States, 1977-1980, Volume XVIII, Middle East Region; Arabian Peninsula, eds. Kelly M. McFarland and Adam M. Howard (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2015), Document 37.

[22] Ibid, Document 90.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid, Documents 112 and 113.

[25] Ibid, Document 114.

[26] Ibid, Document 26.

[27] Ibid, Document 20.

[28] Ibid, Document 126.

[29] Ibid, Document 20.

[30] Ibid, Documents 126 and 127.

[31] Ibid, Document 129.

[32] Gady, F.S., 2020. U.S. deploys 6 B-52 Stratofortress bombers to Indian Ocean Island. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2020/01/us-deploys-6-b-52-stratofortress-bombers-to-indian-ocean-island/