First published by the Chartered Institute of Housing, this article co-written by Prof. Christine Whitehead and Prof. Geoff Meen is part of the 2020 UK Housing Review: Autumn Briefing Paper which focuses on the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

First published by the Chartered Institute of Housing, this article co-written by Prof. Christine Whitehead and Prof. Geoff Meen is part of the 2020 UK Housing Review: Autumn Briefing Paper which focuses on the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

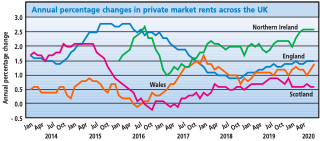

Housing affordability has worsened in the age of Covid-19 for many households – but more for income than for price and rent reasons. Even before the pandemic, house prices nationally, according to the ONS, had increased only modestly – by 2.1% in the year to March 2020 – mainly because of slow real earnings growth. Moreover, past recessions suggest that it would be unusual if there were not a significant decline in house prices into the future, given the projected fall in GDP and rise in unemployment (see page 11). In the private rental market, also using ONS data, rent increases for the year to March 2020 at 1.4 percent were lower than for prices, with a degree of variation across the UK (see chart).

Source: CNS Experimental Index of Private Housing Rental Prices

In the owner-occupied market, the most commonly used indicator of affordability is the median-price-to-earnings ratio.1 This rose from 5.1 to 7.7 in England and Wales between 2002 and 2019 – so most commentators argue affordability has worsened.

But owner-occupation affordability has at least two dimensions: repayment affordability (the proportion of income spent on repaying the mortgage) and purchase affordability (whether the household can afford the deposit). As Compendium Table 44 in the UK Housing Review shows,2 at approximately 18 percent of income for those who have actually bought, repayment affordability has changed little for first-time buyers in the UK since 2000. Moreover, it compares favorably with households paying market rents. Yet for many potential buyers, it is only purchased affordability that is relevant because of the deposit required. With average deposits ranging from around £25,000 in Northern Ireland to nearly £110,000 in London, they are beyond the means of many without access to the ‘bank of mum and dad’.

More than one in five households are now private tenants (over one in four in London). Since its introduction as a component of the Consumer Prices Index in 2005, private rents have generally grown more slowly than house prices.3 This looks like good news but says little about the experience of many of those looking to find a rental property, especially in high-pressure areas. Moreover, even if the increase in rents is modest, the level of rents may still be high relative to household incomes (and compared to mortgage repayments).

Across England as a whole, for those households not in receipt of housing benefit, the median rent was £700 per month in the year to March 2020, equating to approximately 27 percent of gross median earnings. In London, median rents were more than double and took 47 percent of median earnings, well above any accepted measure of affordability.

At the lower end of the market, these figures are mitigated by income-related housing support. Evidence from the English Housing Survey suggests that these benefits do much to reduce financial stress among those in the bottom two income quintiles. However, the limits placed on what people can claim over the last few years mean that the vast majority of private tenants, even those fully dependent on benefits, have to pay some of their rent themselves.

In response to the Covid-19 crisis, the government has enabled rents up to the third decile of the local market to be covered – helping large numbers of lowe income tenants, even though many are still caught by the welfare cap. But the biggest future concern is the large numbers expected to lose their jobs or face reduced earnings and who will find it impossible to pay rents they could cope with before the crisis. Among this group, many will either be ineligible for support or receive far less than their total rent in welfare benefits.

The affordability message is therefore straightforward, but unpleasant. Over the last few years, prices and rents have been rising relatively slowly – but then so have incomes. Even so, many households could be paying less in the owner-occupied sector if they were able to obtain a deposit. Looking forward, house prices may well fall in many areas and maybe more among properties within the grasp of first-time buyers. But that in itself, compounded by less availability of high loan-to-value mortgages, reduces the incentive to buy now. More fundamentally, in both the owner-occupied and rental markets, for the foreseeable future, the core problems are going to be about incomes and the risks associated with those incomes – and it is these pressures which will in turn impact on prices and rents.

References

- Measures of affordability are discussed extensively in Meen, G. & Whitehead, C. (2020), Understanding Affordability: The Economics of Housing Markets. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- See updated version at www.ukhousingreview.org.uk

- But it is important to remember that we are not comparing like with like – the rent index is a figure relating to the private rented stock as a whole; house prices relate only to those properties that have been purchased.

4 Comments