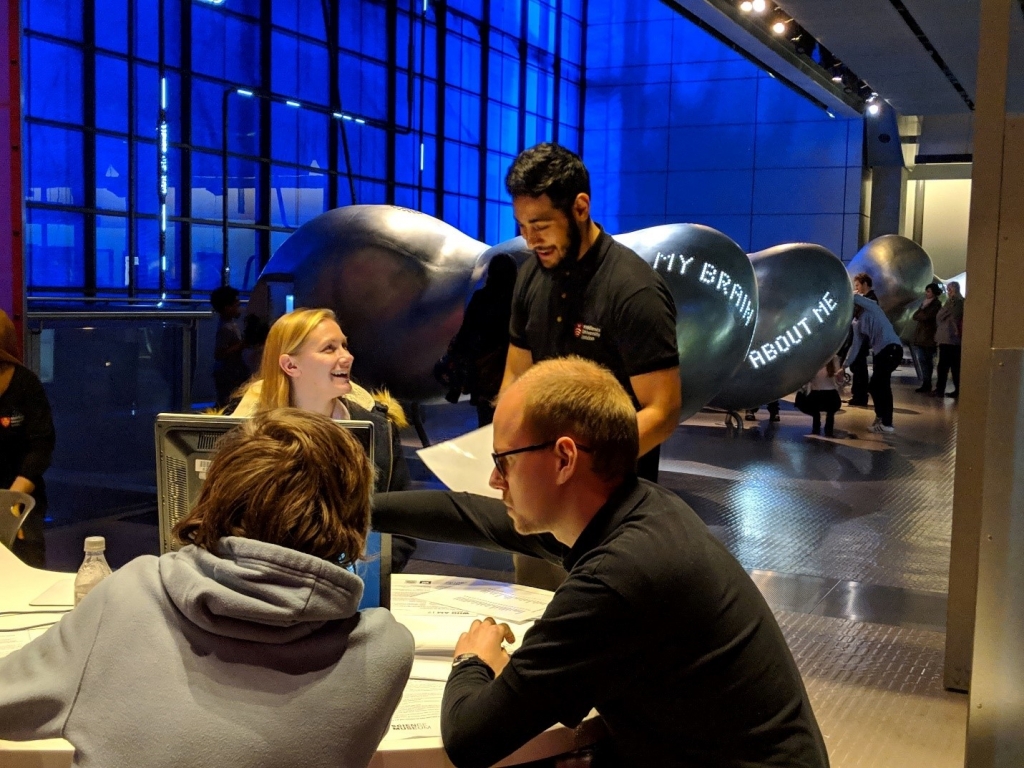

Dr. Heather Kappes investigates how and why we spend our money the way we do, as part of a Live Science residency at the Science Museum.

Across the world, many people aren’t saving enough money to be able to retire from work, or to be prepared for emergencies. Some of these people have very low incomes, but others earn a lot, they just spend most of it.

Personally, I’ve been in both situations. In the years before I went to graduate school, I worked in retail and had low-paying freelance jobs; I lived on credit cards and never felt able to put money aside. After I finished graduate school and landed a job at the LSE, my income was much higher—but somehow, I found myself still living paycheck to paycheck.

My interest in understanding my own spending and saving decisions led me to start studying this topic. Around the 2008 financial crisis, lots of people speculated that what we needed was more financial education training. Unfortunately, research (done by others) suggests that most of this training has no effect on people’s finances. Other research points out that humans seem hard-wired to value the present, making it harder to save for the future. But there’s still a lot we don’t know.

In this research project we’ve designed a computer game to let us scientifically study spending under controlled conditions, using imaginary money, with people ages 8 and up. This game has been programmed by Expilab, who specialize in making research tools that are realistic and engaging. We want to know, in a large and varied group of people of different ages, how choices about spending money are affected by things that are important in the real world, like how much you start off with, how regularly you get income, and how other people around you are spending their own money.

We study these questions by building in some variations of the game—some people get a large amount of imaginary money to start and others get a small amount, for instance. The game lasts for 12 “months” and each month a player either gets income (“gold”) or does not, and then decides how much to spend. People play both with and without information about how their score compares to other players, so that we can see how people’s decisions change depending on what they see others doing. The game is meant to be fun, too!

The problem of insufficient savings—and the stress that goes along with it—has become increasingly visible in the last few years. However, most of us still don’t feel comfortable talking about money, even with close friends. Not knowing how much others spend and save can make it harder to know what we ourselves should do, and harder to support those who need help. One of our goals for this project is to break down a bit of the taboo around money, by giving people a way to start new conversations.

If anyone feels insecure about taking part in this research because they think they’re bad with money, they should keep in mind that almost all of us have room to improve—us researchers as much as anyone! Hopefully by building up a bigger “science of spending,” we’ll be able to make financial education more effective in the future.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This article was originally posted on the Science Museum blog. It is republished on the Management with Impact blog with the author’s position.

- This Live Science event is taking place in the Who Am I? gallery on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays from 11:00-16:30, 15 January – 23 February. Find out more and see how you can take part here.