In the past century, Egypt has seen three major, countrywide uprisings. Harvard University’s Professor Roger Owen spoke at LSE on 9 January, looking back at the events of the riots against the British occupation in 1919 and the Free Officers coup d’etat in 1952 to consider the problems and possibilities that may lie ahead in Egypt. The following is a short portion from his lecture which is available as a full transcript and also as a podcast.

The first revolution I am talking about is the one that took place in 1952. Although it was the result of a military coup, it soon turned into something more like a traditional revolution, although then it turned into an authoritarian dictatorship. But the years after 1952, 1953 and 1954 had something of the revolutionary fervour that one associates with popular revolutions where people come together in order to re-jig the political system, to get rid of the old, to try and create a new constitutional and democratic order. There was an attempt to produce a constitution in 1954–5 by a constitutional commission which was then overruled by the late President Nasser. So it has some of the characteristics of a world revolution, although it is now remembered mainly as a revolution against the British rather than a revolution on behalf of the people.

So first, I think some definitions: what do I mean by revolution and why is that a good way of talking about what is sometimes called the Arab Spring? I mean, ‘spring’ obviously because to begin with, the demonstrations were largely peaceful and therefore aping those of Eastern Europe such as the Velvet springs and things that took places in those parts. But I think it was Amr Moussa, the late Secretary General of the Arab League who said it was a revolution – al-thawra. I think he made that pronouncement in February last year, and I think by calling it a revolution, it gives one access to two useful models and analogies.

One is clearly the parallels with the famous popular overthrows of the old order of France and Russia via a spark, via barricades, via popular uprising. So you have access to that literature and I often think poor Mr Bouazizi who was the spark – Lenin spent a great deal of time wondering when the spark that would ignite the Russian Revolution would take place. He had a newspaper called Iskra – for those of you who remember your Russian history. So it was a revolutionary situation [in Russia], but lacking a spark and so that’s one set of questions people who study these things ask – why did this particular spark happen there and in that particular case? But I’m not going to address that.

Revolutions also lead to an attempt to create a new political and socio-economic order, a prolonged process that often proceeds in fits and starts and the trajectory which is impossible to resist. I remember sitting in Harvard talking to my colleague Robert Darnton who knows a great deal about that French Revolution and thinking about what it was like in the excitement outside the Bastille in 1789 and not at that stage knowing that along the way there was a Napoleon or anything else that was going to happen. This is a reminder that these are open-ended events and very difficult to predict, but one can be sure that they go on for a period of time and that, as I say, there will be fits and starts and false starts and it is very unclear what kind of new order will emerge at the end of them. Perhaps it will lead to a new autocracy by the appearance of someone like Napoleon or Lenin in the name of protecting the revolution from itself.

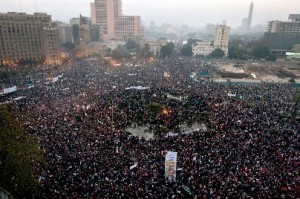

It also gives you access to a vocabulary that includes the notion both of revolution and reaction. So all revolutions are opposed by the people who wish to return to the old status quo or who resent the revolutionary intrusion in their lives in various kinds of ways. I think that was perfectly clear to the young Egyptian revolutionaries in Tahrir Square and is still perfectly clear, that whether you call it the deep state or something or other, there are persons, institutions and associations connected with the old regime who would dearly like to bring the revolution to a halt and to get back to something like the old traditional verities.

Second, if you call it a revolution you get something of a revolutionary programme also drawn from French and American experience, when those obliged to create a new order to replace the old, there seems to be one model: you have a constitution and you have elections. I don’t quite know enough about world history to know why that should be, but it seems to me that if you call something a revolution this is an automatic consequence. The beginning, again, seems to require the creation of a new constitutional order and that has something to do with democracy, something to do with elections, something to do with bringing the people who made the revolution on to the political stage – if only for a moment.

There is a considerable American literature – I don’t know how well it’s known in England – called the ‘constitutional moment’ when people forego their sectional and traditional interests in order to come together to allow a constitution to be made in their name and I think there is still something to be learned from the American political experience. If you read the first sentence of the American constitution – it says ‘We the people of the United States’. What right did those 25 gentlemen who drew up the constitution, how were they able to speak in the name of the people of the United States?

It is something of a trick, it’s something of a moment and we are still in the middle of that. How does one choose the constitutional commission, how does one legitimise it, how do people agree that these particular groups of people will do it in a particular kind of way? And, I think as far as Egypt is concerned, there is something to be learned from Tunisia where, in the elections run by the al-Nahda movement as one knows, the parties were forced to put forward an electoral platform, so that in order to be elected they were not only elected to the Tunisian government, but they were being elected as constitution makers and they were forced to reveal what kind of constitution they wanted and therefore address some of the questions that you have to think about — are you a republic, how parliamentary you are, what are the powers of the president, of the parliament so on and so on. So there has to be some form of national discussion about these enormously important issues.

Professor Roger Owen is a British historian who has contributed extensively to the field of Middle Eastern studies, and the economic and political history of the Middle East, in particular. Last month, he retired from teaching at Harvard University after 45 years of working as an educator, including 19 years at Harvard and 26 years at St Anthony’s College, Oxford, where he was the director of the Middle East Centre four times. He has authored several classic works on the history of the modern Middle East including State, Power, and Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East (Routledge, 2004).

Professor Roger Owen is a British historian who has contributed extensively to the field of Middle Eastern studies, and the economic and political history of the Middle East, in particular. Last month, he retired from teaching at Harvard University after 45 years of working as an educator, including 19 years at Harvard and 26 years at St Anthony’s College, Oxford, where he was the director of the Middle East Centre four times. He has authored several classic works on the history of the modern Middle East including State, Power, and Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East (Routledge, 2004).