by Jonas Bergan Draege

The 2013 Gezi Protests were by far the biggest wave of demonstrations in Turkey’s modern history. In this post I assess the extent and ways in which the country’s political parties responded to the protests. The analysis indicates that the three opposition parties all gave quite a lot of attention to the movement, and even supported some of its demands, but they seemed to do so more to amplify their established positions rather than to reconsider and modify them. Turkey’s parties seemed to care a great deal about the protests, but the strong response may not have been translated into any party change.

The data are based on parliamentary interventions in the Turkish parliament in the 6-week period starting with the Gezi protests on 28 May 2013, until the parliament went on an extended summer holiday from 13 July 2013. I coded parliamentary interventions where representatives mentioned the Gezi Protests, and where they linked those to the protesters’ demands. I consider the four largest parliamentary groups in Turkey, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), and the People’s Democratic Party (HDP).

Who did the talking?

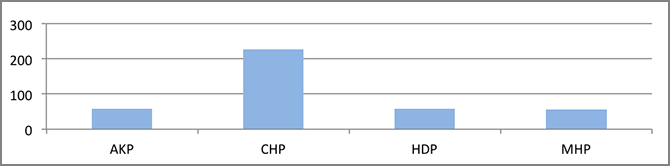

The figure above shows the number of parliamentary interventions in which MPs talked about the Gezi protests. By far CHP representatives mentioned the Gezi Protests in the largest number of interventions (227), while representatives from the three other parties mentioned the Gezi Protests less frequently (59 interventions from the AKP, 58 from the HDP, and 57 from the MHP). Yet the classification may not accurately reflect the parties’ dedication to these issues, as the total number of representatives varies dramatically between parties. In the figure below, I divide the number of interventions by the number of MPs from each party (311 MPs from the AKP, 125 from the CHP, 29 from the HDP, and 52 from the MHP).

Controlling for the number of representatives in the assembly, the figure above indicates that the HDP was the most responsive (2 interventions per MP), closely followed by the CHP (1.8 interventions per MP). The AKP was by far the least responsive (0.2 mentions per MP), while the MHP was somewhere in between (1.1 mention per MP).

Did parties care about what the protestors demanded?

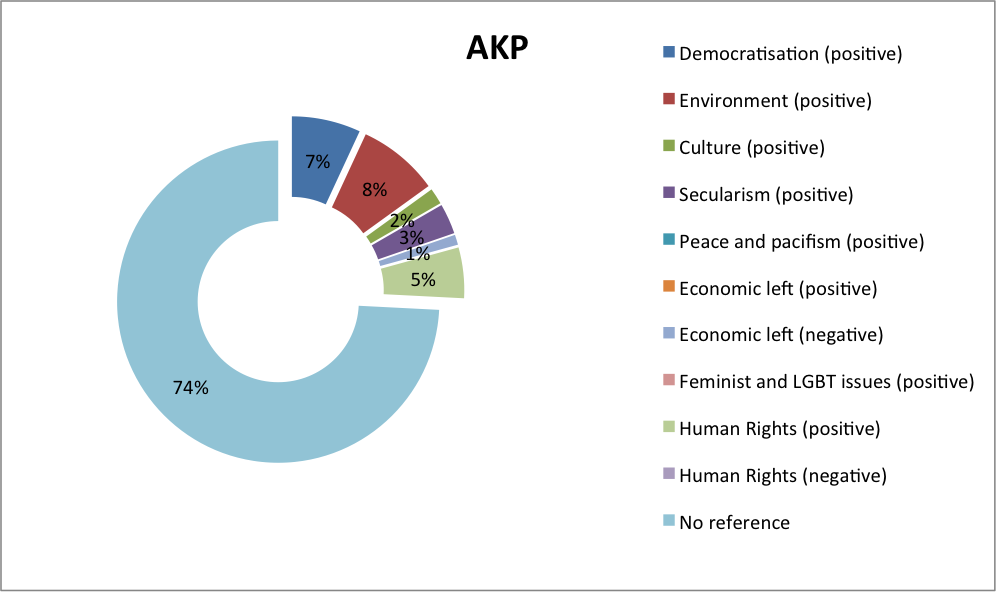

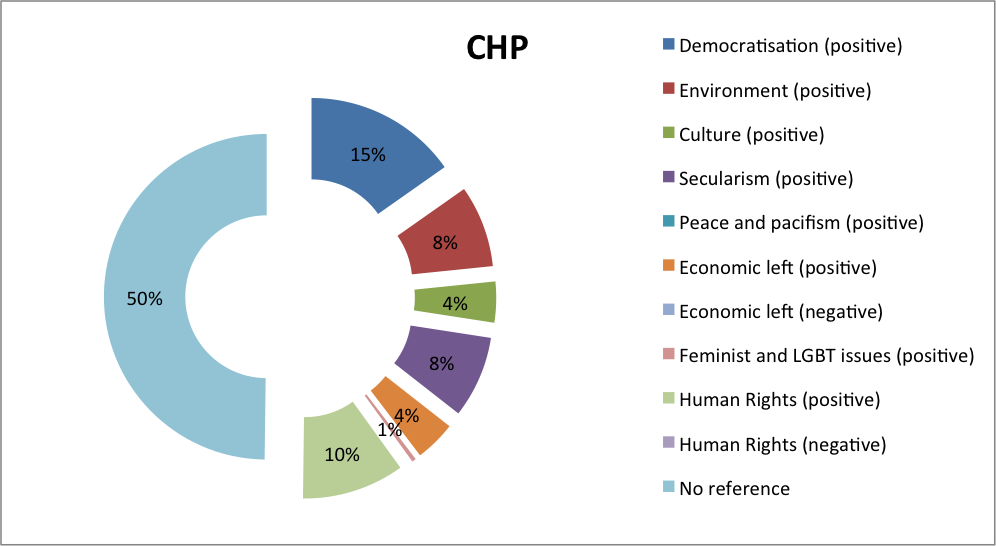

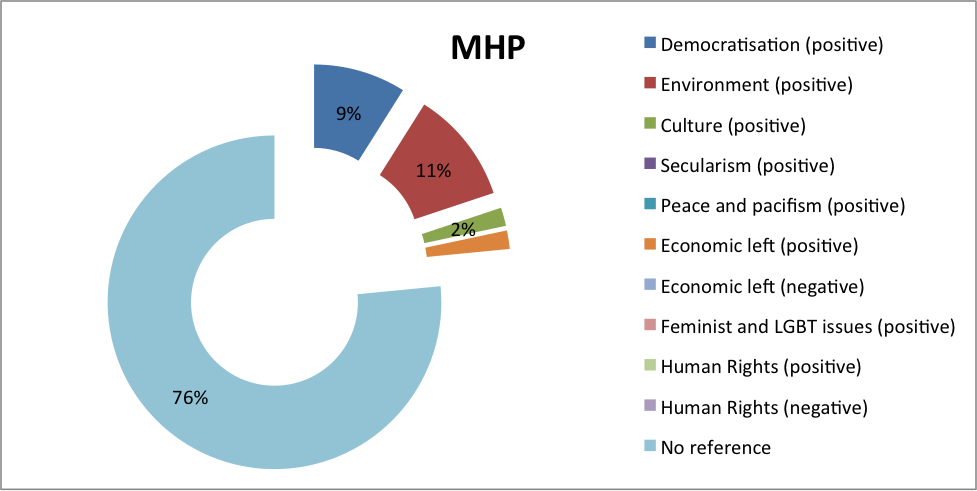

Having established that representatives from the two left-of-centre parties, the CHP and the HDP, were most responsive to the protests, the question remains if the representatives also engaged with the protesters’ main policy demands, or simply mentioned the protests? Although the protests started as a reaction to the negative environmental consequences of the urban transformation of Istanbul, a wider range of slogans and demands were raised as the demonstrations grew and spread to other Turkish cities. The categories of demands considered here were developed based on activists’ webpages and in collaboration with activists in the Gezi Protests.

Categories of demands:

- Democratisation

- Cultural institutions

- Environment

- Secularism

- Peace and pacifism

- Economic left

- Feminism and LGBT issues

- Human Rights

The figures above show the extent to which parliamentary interventions on the Gezi Protests were put in relation to the protestors’ core demands. While the AKP, CHP, and MHP mostly spoke about the Gezi protests without making reference to any of their core demands, the HDP representatives did so to a large extent. Moreover, when the parties did relate their Gezi-interventions to core protest demands, they placed emphasis on different issues. Staunchly secular CHP tied the Gezi protests to demands related to secularism in almost ten percent of their interventions, whereas none of the other parties made this connection in more than three percent of the cases. Conversely, the leftist HDP talked of issues pertaining to the economic left in ten percent of their interventions concerning the Gezi Protests, and about gender equality and LGBT rights in 5 percent of these interventions. The third opposition party, MHP, which places a lot of emphasis on national order and has nurtured relations with fascist militias in the past, did not show any concern for human rights when talking about the protests, in sharp contrast to the other three parties.

Some of Turkey’s parties responded frequently to the Gezi Protests, but in most cases they did so without referring to any of the protesters’ demands, or they referred to issues that already constituted an important part of their agenda. Why did they link the protests to such different issues? One reason might be the large variety of issues to choose from. The large diversity in the demands put forward by the movement gave leeway for parties to choose which demands they wanted to respond to. Indeed, some studies of protest efficiency indicate that movement success is related to having specific and limited goals. This in turn poses a dilemma for movements – expanding the variety of demands may secure more participants in demonstrations, and therefore also more attention from parties. But retaining narrow and specific demands may be the only way to ensure that politicians do not cherry-pick demands and shape them according to their pre-existing agendas.

By extension, the results here indicate that we perhaps should be cautious of equating party response to party change when we look at how social movements are responded to. Parties may respond without making any changes, just as they may change without responding to a movement. In order to get a stronger indication of whether parties changed as a causal effect of the movement, we need to expand the current data to cover several points in time before and after the protests.

What do the current data tell us about Turkish politics? To be sure, the frequency with which parties talked about the Gezi protests highlight the political potency of the events. Both HDP and CHP seemed to consider the Gezi protests a political force in both local and general elections the following years. Furthermore, in an earlier analysis, I have argued that the protests may have had an effect on practical politics as well, in that local politicians in municipalities with a lot of protests allocated more resources to expanding cultural centres and urban green spaces after the events. Yet the Gezi Protests do not seem to have had a strong leverage over larger decisive issues in the parties. Less than a year after the protests, the CHP promoted candidates belonging to the conservative and nationalistic wing of the party in several key cities, and for the Presidential elections a few months after, they put forward a compromise candidate with the MHP. The Gezi protests therefore seem to have had a limited effect on the main opposition party’s choice of election candidates. On the other hand, the events may have created a basis for objecting to such party decisions. The CHP leadership’s choice of candidates in the local and presidential elections caused a spontaneous, Occupy-inspired demonstration among the CHP’s youth and progressives, reminding the party leadership of their endorsement of the Gezi Protests less than a year earlier. Representatives’ responses to the protests may extend beyond mere lip service. If representatives are held accountable for what they said during the heated summer months of the protests, the legacy of the protest may prevail for longer than representatives wish for.

Jonas Bergan Draege is a PhD student in Political Science at the European University Institute. His PhD project focuses on the relationship between protests and institutional politics, with a focus on the Gezi Protests in Turkey. He earned his MPhil with distinction in Modern Middle Eastern Studies at St. Antony’s College, the University of Oxford, in 2013. He tweets at @JonasDraege.

Jonas Bergan Draege is a PhD student in Political Science at the European University Institute. His PhD project focuses on the relationship between protests and institutional politics, with a focus on the Gezi Protests in Turkey. He earned his MPhil with distinction in Modern Middle Eastern Studies at St. Antony’s College, the University of Oxford, in 2013. He tweets at @JonasDraege.

2 Comments