by Ruth Mabry

This is the third post of a 3-part series on urbanisation, public open spaces and physical activity in Oman.

Urban planning in Oman has taken little consideration in designing open spaces that belong to the public realm and support physical activity. The parks described earlier are the main way the capital area has responded, concerned primarily with beautifying (and escaping) the urban landscape. This might be due to the tendency to equate physical activity to ‘athletics’, ‘exercise’ or ‘working out’, forgetting that daily life activities like walking or cycling also qualify as physical activity, like a brisk 10-minute walk to work or to the store.[1]

An urban environment that promotes physical activity in all areas of life, including travel by foot or bicycle, can make physical activity a part of people’s daily lives. The deliberate pursuit of this strategy in matters of urban design would go a long way toward meeting the WHO’s action plan for reducing NCDs and the UN’s sustainability goals. Since active travel is the most common domain of activity in Oman, as opposed to occupational or leisure, appropriately designed public open spaces are absolutely essential.

As the Muscat area continues to grow and develop, Oman is faced with a choice between car-dependent urban sprawl and a more deliberate planning approach that can (also) encourage walking and cycling. The UN Habitat toolkit provides useful advice on this issue, couched in terms of walkability and mixed land use:

Promoting walkability is a key measure to bring people into the public space, reduce congestion and boost local economy and interactions. A vibrant street life encourages people to walk or cycle around, while a rational street network enables necessary city administrative services to be offered within walking or cycling distance and ensures security. High density, mixed land use and a social mix make proximity to work, home and services.

Literature on physical activity and health prioritises mixed use areas that include a range of destinations (work, school and essential services) with complete networks of travel – footpaths, bikeways and public transportation – that support active transport and recreational activity. The elements of urban design found to have the most positive associations with walking are residential density, connected street patterns and land use mix.

Currently, the urban landscape of Muscat Municipality prioritises motorised transport with limited consideration for pedestrians (and none for cyclists). Three communities in the capital area illustrate an alternative vision for the capital area, based upon the principles advocated by urban planners and physical activity experts.

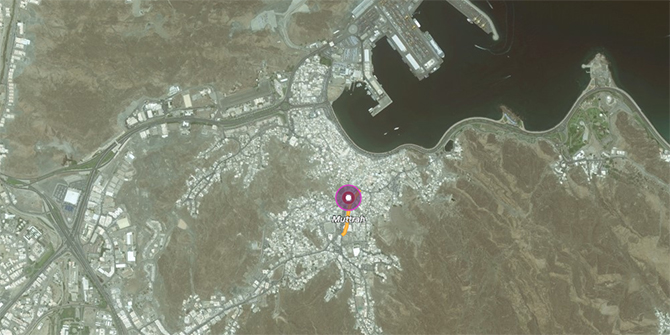

The most well-known community is Muttrah, a traditional neighbourhood along a narrow strip of land between the mountains and the sea (Figure 1), popular for tourists and residents alike[2] for the traditional souq, the long corniche bordering the sea (Figure 4), its restaurants/cafes and parks. During the past century, this compact community grew organically from a small fishing village to a sea port with the highest population density in the country. The central gathering places (souq and corniche) are within easy walking distance for residents, illustrating how an urban area can meet all three of the key elements of a highly walkable neighbourhood: high density, mixed use and high connectivity.

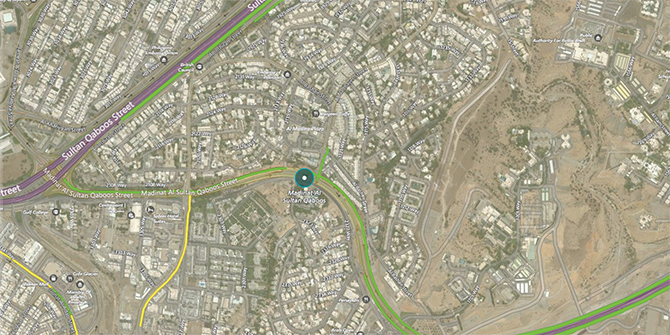

The other two neighbourhoods are newer carefully planned communities with a central shopping area that hosts essential services and leisure activities, which promotes social interaction among residents. This central hub, in addition to the network of sidewalks in each neighbourhood, also encourages a culture of walking. The first is Medinat Al Sultan Qaboos, an older up-scale residential community (MQ, Figures 2 and 5); the second, Al Mouj (Figure 3 and 7) is a luxurious seaside community where the walkways are shaded and green, and the community centre, The Walk, is car-free during the weekend (Figure 6). Although neither are as densely populated as recommended by the UN Habitat guide, these are mixed-use areas with high connectivity of sidewalks. Both neighbourhoods target wealthier population sub-groups, especially the expatriate community.

If Oman is to meet the global goal of reducing physical inactivity by 10%, urban planning and design must incorporate factors that have been found to increase walkability and other forms of active transport. This is particularly important since the neighbourhoods discussed here are rare and increasingly serve only wealthy Omanis, expatriates and foreign tourists. A number of large-scale developments currently being planned, like the expansion of Muttrah’s waterfront, the development around Duqm port and the new city of Madinat Irfan, provide the opportunity for change. However, to really have an impact and meet this goal by 2025, existing communities, where a majority of Omanis live, need to be carefully (re)designed. Otherwise, the trend towards urban sprawl – fuelled by a car-dependent culture – will continue unabated.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the WHO.

More Posts in the Series

[1] Three 10-minute bouts of active travel (walking or cycling) just as easily meets physical activity recommendations as a continuous 30-minute session (of exercise).

[2] Many Omani residents have moved to newer developments; three-quarters of the population are now expatriates.

1 Comments