by Ruth Mabry

This is the second post of a 3-part series on urbanisation, public open spaces and physical activity in Oman.

Formal parks and gardens are relatively new features for a desert country like Oman; the first, Naseem Gardens, only opened in 1985. Muscat Municipality has declared its commitment to green spaces by noting their importance for humanising the city as well as their mental health benefits. Over the past 30 years, the total acreage of public gardens in Muscat has increased from 75,000 m2 to 2,600,000 m2.

But these numbers are deceiving: despite the capital’s reputation as a green haven, public park acreage in Muscat is limited to barely 2 m2 per person, which is quite low compared to green area standards (5.8– 9.5 m2 per capita) for countries of the GCC.

To be fair, this measure of acreage does not include other (formal and informal) spaces maintained by the government such as public walkways (Figure 1), linear parks (Figure 2), recreational grounds (Figure 3), playgrounds, public recreational facilities and the long stretch of beaches along the northern coast of the city. Their inclusion would certainly increase per capita share of public open space, but even this is unlikely to meet expected standards.

These efforts to beautify the city are admirable, but the focus on ‘greenery’ merely decorates an environment already recognised as dehumanising. More importantly, such projects ignore the il/logic of (haphazard) urban design in the region which is often more concerned with ‘enhanc[ing] the efficiency of traffic’ than honouring the people centred tradition of Omani urban design. Until the unspoken assumptions of the current urban planning mindset are made explicit, the car (and the imperative of efficiency) will remain king.

The design of parks and gardens in Oman, like its urban design, are highly influenced by western models and are aimed to showcase progress and modernity associated with the country’s new oil wealth. These designs usually include large expanses of grass, ornamental plants, water features and minimal shaded areas, such as Al Sahwa Park (Figure 4). This unnatural greening of the desert terrain places significant demands for maintenance, quite at odds with the ecological and cultural wisdom of traditional practices of agriculture and land management.

These beautifying efforts also seem oblivious to the meaning and significance of the ‘public realm’, a term that contemporary urban designers/planners use to describe places – both physical and socio-cultural – that people can enjoy and use. Since the construction of cities is usually ruled by a different logic, these spaces must be developed (and managed) deliberately. And they need not be restricted to decorative parks and gardens: as places that belong to the community, they can also include streets, footpaths, squares, extending to riversides and seafronts.

The United Nations has endorsed this broader understanding of public space is in its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, specifically Target 11.7, which aims to ‘provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities’ by the year 2030. Not only does this recognise the importance of public open spaces, it also gives priority to their accessibility to specific subpopulations. If Oman were to expand its conception of public space beyond ‘greenery’, not only would it work towards meeting the UN’s 2030 sustainability goals, it would also address the public health crisis (addressed in the previous post – insert link) associated with rapid urbanisation, physical (in)activity and the development of chronic non-communicable diseases.

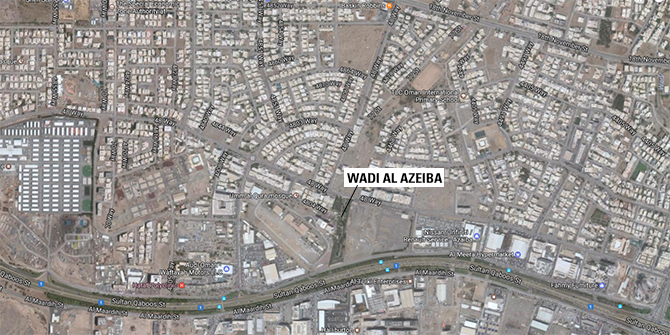

An example of such a broadened approach to public space is provided by the recently developed Wadi Al Azeiba Park (Figures 3, 5 and 7), a small carefully landscaped neighbourhood park developed a few years ago in a wadi bed (a barren flood-prone area). Wadi beds typically remain unused; at times, they are used as illegal dumping grounds for commercial waste. The simplicity of the park is actually a sophisticated design that follows the natural form, using drought tolerant plants and limiting grassy areas, while the lowest area is pebbled and shaped like a stream. Like more traditional parks, there are a variety of functional areas such as shaded areas for sitting and socialising, a green area for children to play in and a circular walkway. The remaining (undeveloped) portion of the wadi bed, the remaining portion (Figure 5) could be designed to provide an alternative car-free route to the beach (2 km away (Figure 6)), which would further expand the walkability of this residential area.

This park differs from other parks in Muscat in a number of important ways, not least of which is the design which is attuned to the natural layout of the land. It also has a much larger ratio of shaded expanse and is not fenced in, allowing local residents easier access to the park, day or night. Well-lit pathways ensure easy accessibility for all residents but especially older adults, children and people with physical disabilities.

The authors of Urban Oman, a study of the ‘radical spatial transformation’ of the Sultanate, conclude their study with the following observations about the ecological dimension of urban development in Oman:

The current process of urbanisation fosters low-rise and low-density neighbourhoods irreversibly converting limited virgin and agricultural land. Natural resources including habitats, land and fresh water are at risk as the balance between environment and urban development is disturbed. Thus, strategies to re-densify and transform neighbourhoods to become multifunctional and diverse, resilient should be developed.

In this context, the development of Wadi Al Azeiba Park provides a more sustainable and ecologically sound model for designing public open space. Its use of sustainable and environmentally appropriate methods and a culturally appropriate aesthetics, responds to the climatic and environmental constraints of the region. As a bonus, parks like this can contribute to the expansion of the public real and support a more healthy lifestyle of active living.

Part 3 of this series continues this examination of public open spaces by looking at the issue of walkability and the street-scape.

Ruth Mabry is Visiting Fellow at the Kuwait Programme, LSE Middle East Centre researching urbanisation and physical activity in the GCC, taking Oman as a case study in Oman. She is also National Professional Officer at the Country Office of the World Health Organization (WHO) in Oman.

Ruth Mabry is Visiting Fellow at the Kuwait Programme, LSE Middle East Centre researching urbanisation and physical activity in the GCC, taking Oman as a case study in Oman. She is also National Professional Officer at the Country Office of the World Health Organization (WHO) in Oman.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the WHO.