by Martha Mundy

#LSEYemen

This memo was presented at a workshop on ‘Yemen’s Urban–Rural Divide and the Ultra-Localisation of the Civil War‘ organised by the LSE Middle East Centre on 29 March 2017.

‘Increased fighting along the Western Coast which is effectively limiting the flow of life-saving commodities, including food staples, into Al Hudaydah Port is aggravating an already terrible humanitarian situation in Yemen. … The inhumanity of using the economy or food as a means to wage war is unacceptable and is against international humanitarian law. … The best means to prevent famine in Yemen is for weapons to fall silent across the country and for the parties to the conflict to return to the negotiating table.’

Statement of the UN Humanitarian Coordinator in Yemen, Jamie McGoldrick, 21 February 2017

‘The one exception to opposition to offensive military actions would be a government-led, Coalition-supported effort to re-claim control of the Red Sea coastal city of Hodeidah and the road from Hodeidah to Sana’a. Hodeidah is the principal port supplying North Yemen. The U.S. should back Government/Coalition efforts to capture the port…’

Statement of former US Ambassador to Yemen Gerald M. Feierstein to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, 9 March 2017

Introduction

Almost two years since the beginning of the war, McGoldrick calls for al Hudaydah to be spared military occupation, and Feierstein for the USA to hasten Coalition occupation of the port city. Saudi–Emirati Coalition seizure of al Hudaydah would cut the highlands from the sea. This recalls one of the triggers of the war: a constitutional decision by the Hadi government on 10 February 2014 to make Yemen a Federal Republic of six regions. The ‘Azal’ region (Sana’a, Dhamar, Amran and Saada) was to be separate from ‘Tihamah’ and without direct access to the sea.

War requires constant attention to the events of its unfolding rendering it difficult to see overall patterns. Transport around the city of al Hudaydah was targeted from the early days of Coalition bombing, but the port itself was spared as ships were controlled by the Saudi naval blockade. In the initial months of the war (March–July 2015) the targets were mainly military. When this did not produce surrender in Sana’a, the Coalition increasingly targeted cultural heritage and economic infrastructure. As part of this, the port and food storage facilities of al Hudaydah were struck first over two days in mid-August 2015. This can be taken as the beginning of a second phase in the war, pursued massively in the following two months. It is on a less well known part of the targeting of economic infrastructure, that of agriculture and rural life, that my work focuses. The bombing of rural Yemen appears to have been central in the second phase of the war that extended, with many pauses for negotiation, for over a year to September 2016. When the targeting of economic infrastructure did not lead to surrender, tactics shifted from the autumn of 2016 into yet a third phase of war which today focuses on geo-political control over the Red Sea, division of former South Yemen, and closure of the Yemeni market economy as a whole. In the below, I briefly examine the bombing of rural Yemen over the period March 2015 – August 2016 during what I have called the first and second phases of the war.

Why rural Yemen? Simply put, it represents the bulk of the country: 65% of Yemen’s population still lives in dispersed villages, and over half of the population relies in part or in whole on agriculture and animal husbandry. Villages, sites of food production, are inevitably less ‘visible’ in media than the urban centres.

Before we turn to the overall patterns, it is necessary address the structure of information and silence that prompted me to try to shed light on the impact of the war on rural Yemen.

Character of Information in Western Media

Over much of the first year of the war Western news media had little coverage of the conflict. This was not just the result of a political editorial decision. Journalists could not enter Yemen easily since the Saudis controlled all flights and passengers to Sana’a airport. Few Western journalists had links with Yemeni journalists who, along with Yemeni rights organisations, worked to document the strikes.

The silence was, however, not only one of journalists but also of international institutions well established in Yemen. During President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s rule (1978–2012) outside ‘aid’ organisations had come increasingly to determine economic policy. The resulting ‘development complex’ comprised organisations of different scales: international (World Bank, UN and affiliates the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the World Food Programme (WFP)), regional (Arab Fund for Development, the Islamic Development Bank (IBD), and the EU), national (British, Dutch, German, US development agencies), and non-governmental (Oxfam, Save the Children, Care, MSF). In something resembling a government of divided responsibility, the development complex dictated economic policy, particularly agricultural and food policy, and the Yemeni state oversaw law, education, core health services, and the military, police and security forces (the last, according to one study, amounting altogether to over 40% of the state budget in 2011).

Following the withdrawal of Gulf and Western embassies from Sana’a in the run-up to military action, the major international organisations departed or left only a skeletal team. It was the NGOs, Oxfam, MSF and among the human rights NGOs, HRW, which reported throughout. Of the international organisations only the International Labour Organization (ILO) undertook new work with the Central Statistical Office in Sana’a to produce an updated labour market survey in January 2016. What had been a development complex became in the course of the second year of the war a kind of parallel government of humanitarianism in Yemen. In this capacity, the UN agencies have begun to resume work and to recover a voice echoed in the Western press.

The resulting picture of the war is vivid in incidents but without an image of the overall patterns of bombing and hence devoid of interpretation of the strategy behind the bombing.

There are specialised units for the compilation of such data. The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery in the WB declared its work inside Yemen closed. The major agencies (UN/WB/EU/IBD) formed a partnership for Yemen for the purposes of a Damage Needs Assessment. In late April 2016 its officials were asked why in a country such as Yemen their work focused on four cities, they answered that in a month’s time the second stage would begin to cover rural areas and justified the urban focus in terms of cost efficiency. On May 6 2016 a briefing was made on the preliminary report by this partnership, but the whole was not released publicly. Given what the ILO Damage Assessment Report found seven months into the war, the consortium presumably had reasons not to make public damage assessments for rural areas. The ILO wrote: ‘…displacement affected mainly the rural population (two-thirds of those displaced came from rural areas) and women…. Agriculture has been the sector most affected…with a loss of almost 50 per cent of its workers…’

Targeting Rural Yemen

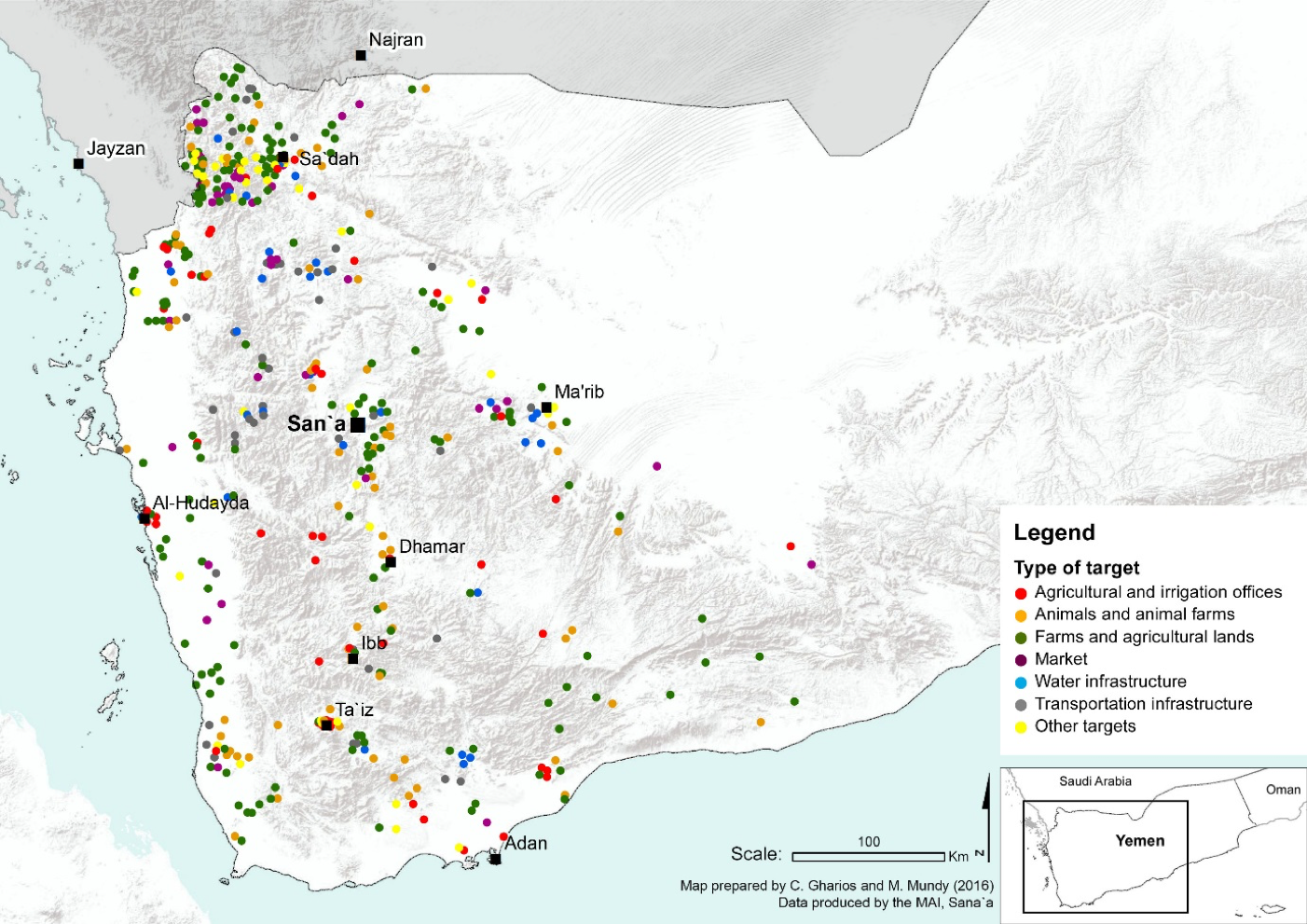

In the face of the ongoing silence of those with multi-million dollar budgets, we have made modest efforts to try to chart the wider pattern of targeting in rural Yemen. The first step in our analysis was to map data compiled by the extension officers of the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MAI) covering the period March 2015–August 2016. This was completed in October 2016. At the time of writing we are working on linking that data to a further set of data from the Yemen Data Project which covers strikes from March 2015 to date. Essentially the two corroborate each other; the YDP reveals that the lists from the MAI are indeed conservative.

The detailed results will be published elsewhere; here I present only a graphic representation of the total targeting by governorate based on the MAI data for the first 15 months of the war.

The data reveal that agricultural land was the target most frequently hit in every governorate save Shabwa and al Mahwait (where the road to Sana’a was the main target). According to FAOSTAT in Yemen agriculture covers just under 3% of the land, forests 1%, and pastures roughly 42%. In short to target agriculture requires a certain aim.

Placing the rural damage alongside the targeting of food processing, storage and transport in urban areas, we find strong evidence that Coalition strategy has aimed to destroy food production in the areas which the Houthis and the General People’s Congress (GPC) control.

Wars, and above all this war, are forms of experimentation. Damaging agriculture and controlling food imports have long formed part of the arsenal of techniques employed against the much smaller territory of Gaza. Here the experiment is on a larger scale with many different parties engaged in the fray. Today the war appears to have entered a third phase with a Coalition attempt to take the coastal plain with its ports and to use control of the banks and government salaries to bring the north economically to its knees. An official of the MAI responded negatively when asked recently whether the Ministry had continued to log damage to agricultural infrastructure beyond August 2016, responding that ‘all has already been bombed’.

In a longer-term perspective, it appears that this war, prosecuted by countries in which oil, armament, and the dollar loom so large, aims at a further devaluation of Yemen’s rural human and animal labour beyond that already brought about by the oil–dollar economies and the policies of the ‘development complex’.

Martha Mundy is Professor Emeritus in Anthropology at LSE. She is a specialist in the anthropology of the Arab World whose research has concerned anthropology of law and the state, the comparative sociology of agrarian systems, and the anthropology of kinship and family.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to the IDRC-funded AEH grant at the American University of Beirut for financial support for cartographic work by Cynthia Gharios. In this paper ‘we’ refers to Cynthia and myself, but I take all responsibility for the interpretation given of the results.

Other Contributions in the Series

- Yemen’s Rural Population: Ignored in an Already-Forgotten War, Helen Lackner

- The Battle to Control the ‘Commanding Heights’ of the Yemeni Economy, Rafat Al-Akhali

- Saada: Ground Zero, Gabriele vom Bruck

- From Protesters to Politicians: The Rise of the Houthis, Nawal Al-Maghafi

- Taiz Youth: Between Conflict and Political Participation, Maged Sultan

- Community Responses to Conflict in Taiz, Kate Nevens

- Healthcare under Siege in Taiz, Sophie Désoulières

- Aden: Relief Challenges and Opportunities, Awssan Kamal

- Marib: Local Changes and the Impact on the Future of Yemeni Politics, Alkhatab Al-Rawhani

- Hadhramout from Federalism to Civil War: Demands and Realities, Baraa Shiban

20 Comments