by miriam cooke

This memo was presented part of a workshop organised by the LSE Middle East Centre on 13 June 2018, looking at Tribe and State in the Middle East.

During the past twenty years, tribes, tribal structures, functions and leadership have attracted the attention of writers in various disciplines, including anthropology, political science, pop psychology and business. Whereas social scientists argue over the vexed meanings of tribe and how tribes function in modern contexts, do-it-yourself psychology and business texts have no problem with these issues. Their notion of the tribe is straightforward; it affords a brilliant model for life and economic success. Recently published mass-market books recommend emulating a formula derived from their definitions of tribal structure to help individuals and businesses thrive. Dave Logan et al., for example, assert that effective tribal leadership “helped humans survive the last ice age, build farming communities, and, later, cities. Birds flock, fish school, people ‘tribe’… The members of your tribe are probably programmed in your cell phone and in your email address book… Tribes are the basic building block of any large human effort” (Tribal Leadership 2008 cited in cooke, Tribal Modern 2014). For Jonah Goldberg, the tribe materialises a natural, perennial and universal human desire to belong to homogeneous groups. There is, he writes, “something deeply attractive” (Suicide of the West: Rebirth of Tribalism 2018, 13) about cooperation that includes irresistible urges to exclude, to punish and to vaunt identity. Our primordial “inner tribesman” apparently values power, loyalty, reciprocity, and honour, and rejects pluralism because it “requires tolerance and forces us to open ourselves up to the possibility that our identity is not the only true or right one” (62). Tribes reject democracy because it threatens tribal power politics. Theorists validating Goldberg’s tribe-as-natural argument include: Charles Darwin for whom “The tribe that works together survives to pass on its genes”; Elias Canetti whose crowds draw on “tribal passion”; and Karl Marx who had hoped that if “the workers of the world, bound together in tribal solidarity, they could overthrow their masters.” Although Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddima is not cited, his notion of tribal solidarity or ‘asabiya rings loud. These contemporary and classical writers who invoke the tribe are interested less in the actual structure and formation of specific tribes, and more in the idea of the tribe.

As a student of Arab cultures, I, too, am concerned with this idea of the tribe but I understand it to function in an unprecedented way in today’s Arab Gulf. In Tribal Modern: Branding New Nations in the Arab Gulf (2014), I analyse the recent emergence of tribal identities as part of a distinctive geo-political brand that has shot Gulf countries to international prominence. From an economic perspective, it is noteworthy that more millionaires are flocking to the UAE than anywhere else in the world.

Between 2003 and 2010, I visited the Gulf region on several occasions and spent extended periods in Qatar. I was struck by the oddly harmonious juxtaposition of ultramodern starchitecture and cutting-edge cultural projects alongside tribal emblems and values. Why, I wondered, did mega-rich Gulf Arabs intent on rapid modernisation and playing an active role on the global stage insist on their tribal identities? I was surprised when Gulf Arab students respond positively to my question about tribal and modern fitting together.

In a situation where foreigners vastly outnumber Gulf Arabs, the need to distinguish themselves and their rights to uncontested natural resources has become urgent. The tribal provides the key distinguishing feature. Tribal in today’s Gulf is not traditional, not primitive; not natural; not perennial; not anti-modern. The tribal shapes a unique brand that modern Arab Gulf nation-states are marketing.

How are we to understand the tribal in the brand? It marks privilege, unique rights to natural resources and citizenship, but only for those with a pure past. If a pure past free of outsiders does not exist, it can be created. Heritage projects help to erase pre-national hybrid ethnoscapes marked by millennia of exchanges between Mesopotamia and Indian Ocean (attested to by the discovery of second millennium BCE Dilmun seals); Portuguese; Ottomans; British, Indian subjects of Raj, and French pearl merchants.

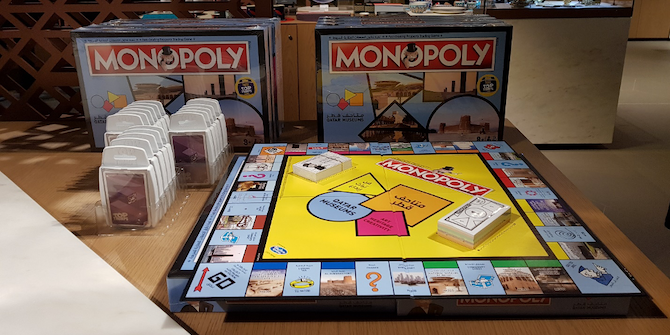

Pure blood refines this citizenship. The new, racially determined nation-states hold the monopoly on exclusion that may include arbitrary revoking of citizenship for those no longer deemed worthy of membership or absolute denial of citizenship to foreigners whose blood is not pure. Writing about newly valorised tribal identities in Sub-Saharan Africa, John and Jean Comaroff explain that when ethnically defined populations identify a stake profit-sharing corporations, “their terms of membership tend to become an object of concern, regulation, and contestation. And the more they do, the greater is their proclivity to privilege biology and birthright, genetics and consanguinity, over social and cultural criteria of belonging” (Ethnicity, INC. 2009). This is what is happening in the Arab Gulf.

Islam deepens claims to citizenship and its exclusive right to ownership of oil-rich land and gas-rich sea. In a 2010 survey that my Virginia Commonwealth University-Qatar students conducted with their peers, the question of where the individual’s tribe came from and when, often elicited the response: Western Arabia and the seventh century. Tracing origins, even if indirectly, to the Prophet Muhammad enhanced elite identity.

The tribal constitutes the exceptional element in Gulf Arabs’ modern identity. How can this tribal be braided with the modern (too often reduced to Western) in such a way that it engineers the tribal modern brand?

It is easy to see this braiding in heritage sites like Qatar’s national museum, which fuses the desert rose with a spaceship visual, and in sports, where the highly technologised camel racing that sits comfortably with the FIFA World Cup plans for 2022. However, the tribal modern brand is harder to theorise. In Tribal Modern, I argue that the Arab Gulf brand needs to be understood through a new epistemological optic that I call barzakh logic. Barzakh is a Qur’anic term that designates the metaphysical space between life and the hereafter that contains both even as both are absent. Similarly, suspension, meeting and separation between tribal and modern characterise Arab Gulf culture today. Retaining independence and specificities, each shapes the other in a dynamic, cultural-political field that allows neither compromise nor erasure. The tribal and the modern fashion the unique identity and power of today’s Gulf Arabs.

Other posts in this Series:

- Introduction by Courtney Freer

- Tribalism in Middle Eastern States: A Twenty-first Century Anachronism? by Richard Tapper

- Tribe and State in the Contemporary Arabian Peninsula by J. E. Peterson

- The Syrian Civil War: What Role do Tribal Loyalties Play? by Haian Dukhan

- Tribes and Tribalism in a Neoliberal Jordan by Jessica Watkins

- From Revolutions to Elections: When Tribes Transform State Power by Alice Wilson

- The Political Decline and Social Rise of Tribal Identity in the GCC by Steffen Hertog

- On Tribalism and Arabia by Andrew Gardner

- Gulf Nationalism and Invented Traditions by Natalie Koch

- Tribal Social Evolution and Gender: Conflict in Urbanized Tribal Units by Alanoud Alsharekh

- Tribal Revival in the Gulf: A Trojan Horse or a Threat to National Identities? by Maryam Al-Kuwari

This is incredibly interesting. I have been to a lot of tribal villages around the world and even help with some online, but I have not read some of these books. Thank you for sharing your brain…ha. Now I can learn much more. All the best and safe travels.

This is very interesting. A lot to learn about all the places to visit in the world. Thank you for sharing.

As a person that comes from one of the most powerful tribes in the Gulf of 6 million people, this is the most ridiculous and inaccurate representation of tribal politics in the Gulf. The author lacks a lot of information and uses terms that has no relation with the subject such as “barzakh” and cites her experience as an over paid teacher in one of the most corrupt and passive educational systems in a country like Qatar. Unfortunately what disappoints me is not the author but the institution that verifies this as correct and publishes his/her work. The difference between tribes in the Gulf and tribes in Afghanistan for example is that tribes in the Gulf are pre-Islamic and are well documented as a lineage for thousands of years. Also, there is no “creation of pure past”? What on earth are you talking about? Every single major tribe has an identified lineage of ancestors that dates back to Abraham, and everyone else was either adopted or married into the major tribes, we still know and identify each “foreigner” and our political tribal system is not replicated anywhere else because this was our only mode of survival in the desert for thousands of years, we are not Gypsies we are not farmers, we are educated and cultured ethnic tribes that base our communication on integrity and word of mouth, which means belonging to a tribe carries a huge responsibility of representing them with honesty and honor. I am more than happy to offer a true and honest census research on our tribes and can connect you with each tribal leader of all the major and powerful tribes. You can send me an email on smhm9016@gmail.com.