by Suzi Mirgani

Something significant is taking place in Qatar Museums (QM) gift shops: a contemporary Qatari national identity is being constructed through the production and consumption of state-sponsored museum merchandise.

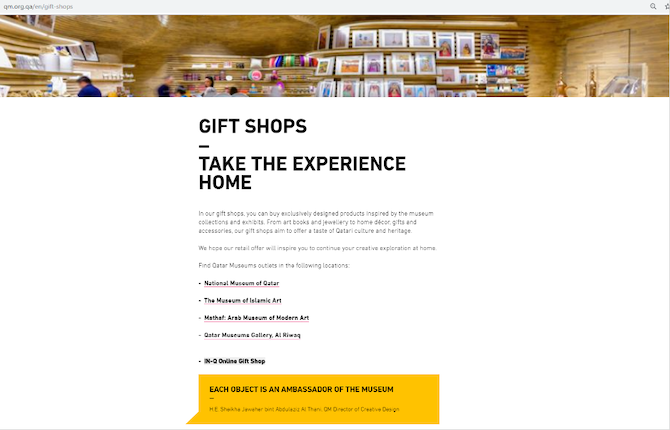

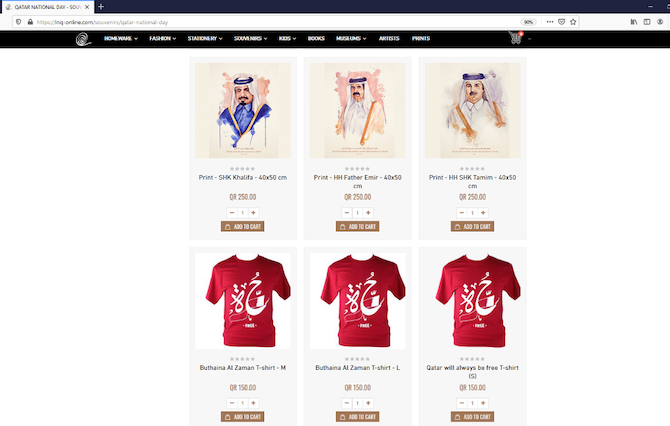

Since QM is a government institution, any museum that comes under its umbrella necessarily has a political dimension. Similarly, since QM gift shops are extensions of these museums, their merchandise is also necessarily expressive of the state. QM gift shops clearly note that ‘each object is an ambassador of the museum‘—and so, by extension, an ambassador of the state (Figure 1).

QM merchandise is symbolically distinguishing Qatar from other Gulf countries—an especially welcome differentiation since the 2017 GCC crisis. As Qatar forges an independent foreign policy path, QM is contributing to the nation with a strategy of ‘souvenir sovereignty.’

Since the Qatari government ‘only began issuing tourist visas in 1989,’ tourism was limited and a souvenir industry nonexistent, prompting people to publicly inquire about ‘where to buy souvenirs in Doha.’ This was a period of time when The Lonely Planet labeled Qatar ‘the dullest place on earth,’ and ‘best known for being unknown.’

Ridiculed for ‘falling off the world’s radar,’ Qatar experienced a rude awakening. Since Qatar was simultaneously enjoying an economic boom, gaining ‘the highest per capita income in the world,’ the country was endowed with the resources and motivation to engage in a national branding overhaul, laying the foundations for mass marketing the 2006 Asian Games—’the largest sporting event in Asia‘ and Qatar’s first major international spectacle.

This was Qatar’s chance to make a personal statement to international audiences with a new and improved image of the country—a rebranded Qatar that was also materially manifest for public consumption in state-sponsored nation-branding souvenirs, with ‘200,000 items of official merchandise sold at Asian Games.’

In the early 2000s, the best-selling items at the old Doha international airport were Nido and Tang sold to the hundreds of thousands of low-income migrant workers. With Qatar Airways’ global expansion, and millions of passengers passing through the airport, ‘local products and souvenirs‘ quickly became ‘the category achieving the highest increase in sales‘ in 2004. There began a strategic push towards turning the country into a bona fide tourist destination.

Souq Waqif was renovated in 2008 from an old souq into a leisure destination, presenting an alternative attraction to Qatar’s many shopping malls. This newly transformed urban space became popular with tourists and residents, and an area ‘distinguished for selling traditional garments, spices, handicrafts and souvenirs.’

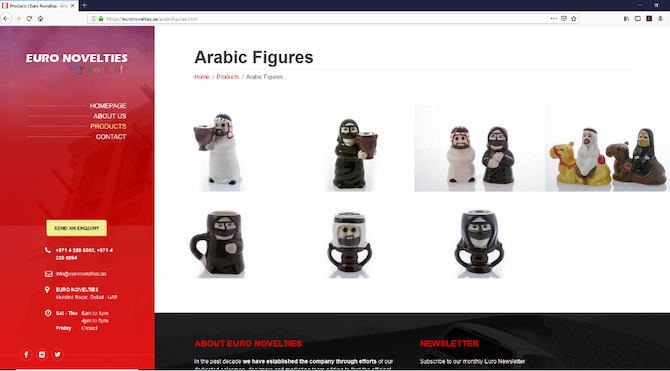

These mass-produced items, however, said very little about a specific Qatari national identity since the very same items are readily available in other GCC states. The market is flooded with tacky representations of a ‘generic Gulf Arab,’ which, before the 2017 blockade, were imported from Dubai (Figure 2).

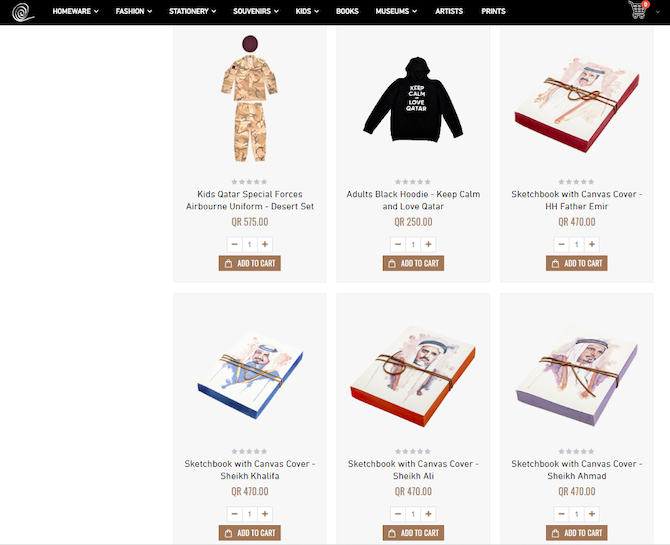

This ‘souvenir identity crisis’ was finally addressed by marketers at In-Q Enterprises—the commercial arm of QM—who forged a direct connection between museum and merchandise; gallery and gift shop; curator and retailer; and state-led museum and visitor-cum-customer. QM began offering a range of products specifically designed to represent Qatar and its cultural institutions. After the 2017 blockade, especially, these commodities assumed an openly politicised character, bearing symbols of the state, the royal family, and the military, and emblazoned with statements such as ‘Qatar will always be free‘ (Figures 3–4).

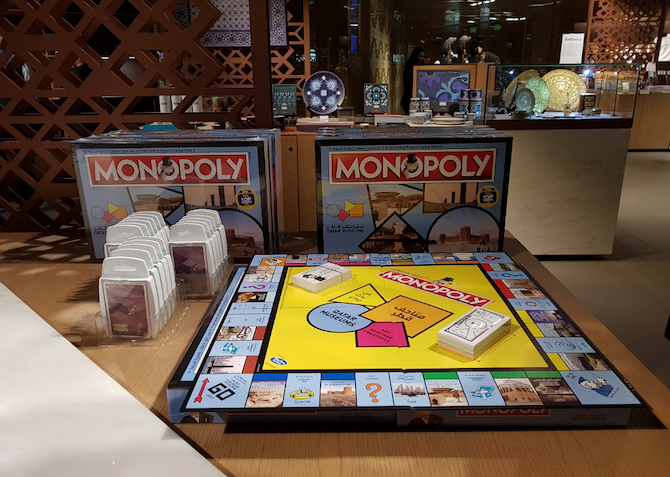

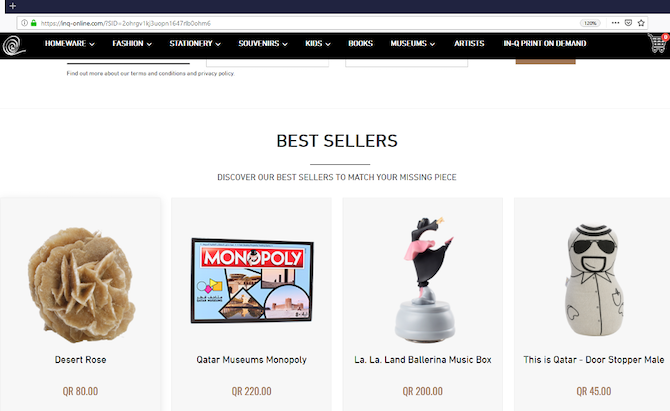

QM merchandise, such as its customised Monopoly board game, is used to educate the (paying) public about Qatar’s most valuable cultural offerings, placing a monetary value on culture and heritage in descending order—from the Zubara archeological site, to the National Museum, to the Museum of Islamic Art (see main picture). Crucial decisions are being made about which site is more important to the national project, and thus of higher value on the board. In a rebuttal to The Lonely Planet’s criticism that ‘most foreign maps of Arabia drawn before the 19th century don’t show the Qatar peninsula,’ QM’s Monopoly has quite literally placed Qatar on the map.

QM merchandise is also materialising an entirely new national symbol—one that is not shared by any of the other Gulf states: the desert rose, which is becoming central to the country’s new national image. It is reiterated across Qatar’s cultural, social, political, and economic sectors: in Jean Nouvel’s architecture of the National Museum of Qatar; in advertisements for the 2022 FIFA World Cup; in hotel lobbies as a sign for visitors; as official gifts given by government and corporate entities; and as ‘best sellers‘ in QM’s gift shops (Figure 5).

These products are not just ‘created,’ they are ‘curated’ with Qatar’s image and future economy in mind. As state institutions, since QM and Qatar’s National Tourism Council are closely related, their marketing strategies similarly coincide. In the country’s 2019 tourism slogan, ‘Qurated for you,’ the state is speaking the language of museums. A winning combination of tourism, culture, and commodities has worked to change Qatar’s international reputation, and The Lonely Planet was obliged to edit its entry to acknowledge Qatar’s cultural ascendance.

Through QM merchandise, Qatar has entered a new stage of national identity formation—one that is tangible, contemporary, culturally-connected, and market-oriented. QM’s attractions and its merchandise have thus become central to Qatar’s tourism strategies; to its future post-hydrocarbon economic vision; and to—limited—civil participation in its national identity.

Museums have always been elite spaces in which there is an invisible dividing line between socioeconomic classes—a division that is even more pronounced at the threshold to the gift shop. Even though QM merchandise can theoretically be consumed by all, the gift shop can actually serve to magnify existing socioeconomic differences, especially those related to low-income migrants—the bulk of Qatar’s population—who can least afford these curated commodities.

More positively, QM works with both Qatari and foreign artists to come up with new products—a promising step in the direction of a participatory construction of the country’s national image. A modern notion of citizenship is being expanded to include a symbolic form of belonging through commodities. This is an allegiance through the market, rather than purely through the state—what Kevin W. Gray terms ‘neoliberal citizenship‘ and what Neha Vora calls ‘neoliberal economic belonging.’

Just as there was a need to create ‘citizens’ in the early days of nation building, there is a need to create ‘consumers’ in the contemporary period dominated by a worldwide culture of consumption.

By consuming national identity in commodity form, citizens, residents, and visitors not only buy it—but are encouraged to buy into it.

This is part of a series emerging from a workshop on ‘Heritage and National Identity Construction in the Gulf’ held at LSE on 5–6 December 2019. Read the introduction here, and see the other pieces below.

In this series:

- Introduction by Courtney Freer

- Examining Kuwait National Museum by Sundus Alrashid

- Urban Planning and Legacy Making in Kuwait by Alexandra Gomes

- Museums as Political Institutions of National Identity Reproduction: Are Gulf States an Exception? by İdil Akıncı

- The New Populist Nationalism in Saudi Arabia: Imagined Utopia by Royal Decree by Madawi Al-Rasheed

- Heritage and Sectarianism in Bahrain by Thomas Fibiger

- Dubai Expo 2020 and Ancient Mercantile Heritage by Robert Mogielnicki

- Managing UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Saudi Arabia: Contribution and Future Directions by Abdulelah Al-Tokhais

- Finding Mariam: the Invisible Woman in National Heritage Mythology by Alanoud Al-Sharekh

- Cultural Attendance: Attracting the Crowds to Museums in Saudi Arabia by Maha al-Senan

- Religion and Heritage in the Gulf: Significant in its Absence? by Courtney Freer

- Historical Archaeology in the Gulf by Robert Carter

- Militarised Nationalism in the Gulf Monarchies: Crafting the Heritage of Tomorrow by Eleonora Ardemagni

- The Practice of Heritage in the Northern United Arab Emirates by Matthew MacLean

- Displaying the Nation in Museum Exhibitions in Qatar by Alexandra Bounia

- Implicit and Explicit Cultural Policies in Qatar: Contemporary Art Production and Censorship by Serena Iervolino

- The UAE State ‘Rebirthing’ of Motherhood: Who is birthing who? by Rima Sabban

The gratuity calculation helps for calculating how much to tip in Qatar. It can be used for restaurants, hotels, barbers, and other types of services. This calculator takes into account the percentage of Qatar’s minimum wage that you earn in comparison to the service provider’s minimum wage.

Molitics- Media of Politics is a platform of all the political happenings. You can get Political News, Election Results and details of Politicians, you want on a single click through this app