by Natalie Koch

This is part of a series of memos presented as part of a workshop organised by the LSE Middle East Centre on 5 October 2018, looking at national identity and the Emirati state.

The idea that the world is divided into separate ‘nations’ is so pervasive today that it can be difficult to imagine how it might be otherwise. But this geopolitical ordering of the world is not a natural state of affairs: people must actively imagine themselves as part of a social community defined as a ‘nation’. This raises the question that continues to puzzle scholars and lay observers alike: How do individuals internalise this geopolitical imaginary and come to think of themselves as belonging to a nation? There are countless ways to answer this question, not just because there are a huge range of groups that call themselves nations, but also because the mediums of practicing and imagining national identity are constantly changing with time. Sometimes these practices are top-down and state-driven. Other times, national identities congeal through more diffuse, bottom-up practices. Most often, there is a mix of the two, as the top-down and bottom-up sources of nationalism each draw fuel from the other’s fire. This dynamic is especially visible in the case of sport, and vividly illustrated by the promotion of so-called ‘heritage sports’ in the UAE.

In the past several years, boosters across the Gulf states have worked hard to bring large, international sporting events to the region. In the UAE, much of this work has focused on elite sport – those globalised sports that attract more affluent participants and spectators. These include high-profile championships from tennis to cycling, sailing, golf and equestrian sport. In promoting elite sport, leaders both seek to cultivate the prestige that is accorded to them, advancing an image of the UAE as a place of wealth and supreme luxury. For example, shortly after Bahrain hosted the first Formula One Grand Prix race in the Middle East in 2004, Abu Dhabi quickly followed suit – opening its impressive US $1.3 billion Yas Marina Circuit in 2009.

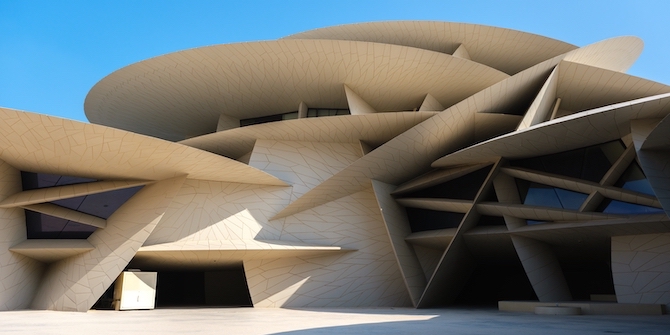

Promoting high-profile elite sporting events is an important means to broadcast an image of the UAE as affluent, cosmopolitan, modern and globalised. As the Yas example suggests, globalised sporting events can be an opportunity to reshape urban infrastructure and position the country’s leading cities (mainly Dubai and Abu Dhabi) as sporting hubs to entice an elite class of tourists. These initiatives arise from the nationalist goal of promoting a positive image of the country and push back against a still-pervasive Orientalist stigma about the Middle East in the West. Promotional materials for elite sporting events actively challenge such negative associations, prominently featuring sparkling images of hypermodern sporting venues set against impressive skylines and gleaming new infrastructure. With this message in mind, it is clear that the target for globalised elite sporting events is primarily international audiences who hold assumptions about the UAE and Emiratis that nationalistically-minded leaders want to transform.

In contrast to the more outward orientation of elite sport initiatives, state leaders have also promoted heritage sports, which tap into more locally-defined notions of Emirati culture and national traditions. As in all realms of the heritage industry, promoting local culture is highly curated and aestheticised in the case of heritage sport in the UAE. While the images and initiatives surrounding heritage sport operate in different discursive spheres from that of elite sport, it ultimately serves a similar role insofar as it aims to advance a positive image of Emirati national identity – one that is both modern and rooted in tradition.

Heritage sport is also somewhat different from elite sport because it more actively engages the bottom-up sources of nationalism among the citizens, who are held up as the primary practitioners and audiences of these sporting endeavours. The state still plays a central role in coordinating heritage sport, however, as it funds festivals, competitions and a range of other activities to support the growth and institutionalisation of heritage sports. For example, a 2013 decree issued by the General Secretariat of the Executive Council in Abu Dhabi established the Cultural Programs & Heritage Festivals Committee – Abu Dhabi, which organises a number of events that promote heritage sport. Another is the Abu Dhabi International Hunting and Equestrian Exhibition (ADIHEX), which is said to showcase some of ‘the main pillars of the UAE heritage, such as the love of falcons and horses, once the symbol of the Arabian civilization, and for its core values like courage, respect of resources and kindness to animals and birds.’ The Committee also coordinates the yearly Al Dhafra Festival dedicated to the ‘Bedouin life and culture’, and includes heritage sport displays encompassing camel and dog racing and falconry. The International Falconry Festival is also organised under the aegis of the Cultural Programs and Heritage Festivals Committee and, as I described in a previous blog post, falconry is perhaps the most prominent heritage sport in the UAE.

Falconry is not the only heritage sport that has been promoted by the state and embraced by the Emirati citizens. The Arabian Saluki Centre, for example, has advanced dog racing as a heritage sport and has hosted an ‘Arab Heritage Saluki Race Festival’ at the Zayed City camel race track. The novel practice of racing salukis is framed as a heritage sport by emphasising the breed’s long history in the Arabian Peninsula, as well as its association with Bedouin culture and falconry. Efforts to promote camel racing work similarly – linking this recently invented tradition to the idea that the camel is an icon of Emirati heritage and national identity. The contrast between the ‘traditional’ and the ‘modern’, characteristic of contemporary ‘heritage sports’ is stunningly illustrated by images of robo-jockeys astride camels, racing around purpose-built tracks. This contrast is also found with the case of traditional rowing, which has also been transformed into a ‘modern’ heritage sport (albeit without robots) by devising an entirely new form of competition, but with traditional materials – in this case, mahmel rowing boats, which were once used as water taxis and inshore fishing boats.

As explained by the Commodore of the Ras Al Khaimah Sailing Association, Daniel Zeytoun Millie, participants have engaged in this ‘heritage sport’ since the 1970s, ‘principally as a way of maintaining the maritime traditions of the coastal peoples of the UAE’. Using similar language, a 2016 article in The National championed a wide range of heritage sports as helping to preserve Emirati heritage. The overall logic of heritage sport is that the raw materials (the cultural forms, practitioners or animals) should be ‘local’, but that the competition itself may be as new and modern as one pleases: the main idea is for the sport to put an aspect of Emirati heritage on display.

If heritage is understood to be a process that constructs meaning about the past, heritage sports are one means of identifying the most valued icons of the past, aestheticising them, and allowing people to directly engage with them – either through active participation in competitions, spectating or passive admiration of the skill and beauty that defines them. In the UAE, promoting heritage sport works through both top-down and bottom-up processes: supported by the state, but actively embraced by many citizen-nationals. The broader set of practices ultimately glorifies Emirati culture and simultaneously celebrates the traditional and the modern. Whether practiced for the watchful eyes of tourists or the unobserved love of sport, heritage sport is intimately connected with Emirati identity narratives today, helping individuals to imagine themselves as belonging to a discrete ‘nation’ and to internalise the geopolitical imaginary of a world divided into nations.

Natalie Koch is Associate Professor and O’Hanley Faculty Scholar in the Department of Geography at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. She is the author of The Geopolitics of Spectacle: Space, Synecdoche, and the New Capitals of Asia and editor of Critical Geographies of Sport: Space, Power, and Sport in Global Perspective.

is Associate Professor and O’Hanley Faculty Scholar in the Department of Geography at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. She is the author of The Geopolitics of Spectacle: Space, Synecdoche, and the New Capitals of Asia and editor of Critical Geographies of Sport: Space, Power, and Sport in Global Perspective.

In this series:

- National Identity and the Emirati State by Courtney Freer

- Assessing Historical Narratives of the UAE by Victoria Hightower

- When Art and Heritage Collide: Artistic Responses to National Narratives in the UAE by Melanie Janet Sindelar

- The State and Museums in the Arabian Peninsula: Defining the Nation in the 21st Century by Karen Exell

- Why More Research on the Bottom-Up Constructions of National Identity in the Gulf States is Needed by Idil Akinci

- State Building, State Branding and Heritage in the UAE by Rima Sabban

- Monolithic Representations of ‘Arab-ness’: From the Arab Nationalists to the Arab Gulf by Rana AlMutawa