by Alexandra Gomes

Kuwait is a high-income city-state emirate with considerable resources, land and oil in particular. In total its national territory covers an area of 17,399 km2, though urban Kuwait only constitutes 424km2, which means that Kuwait still has a significant amount of total land mass available for development even after accounting for all physical constraints (e.g. oil fields, military areas, natural reserves, etc.).

71 percent of the population live in densities of less than 20,000 pers/km2, typically corresponding to detached single-family housing residential neighbourhoods for Kuwaitis. However, there are significant peaks in population density directly corresponding to non-Kuwaiti mixed-use medium density neighbourhoods (max density 52,941 pers/km2). In terms of modal share, 50 percent of commuting trips are made by private vehicles while the remainder are made by bus, taxi and walking. However, 99 percent of Kuwaiti citizens’ trips are made by car, while non-Kuwaitis dominantly travel by buses. There is no mass transit infrastructure in Kuwait.

When compared with Hong Kong, a city state with similar per-capita income levels, Kuwait – with under half of Hong Kong’s population – has already consumed almost twice as much territory for urban land, relies on three times more electricity for residential use (65%) and produces more than three times CO2 emissions (25 metric tons per capita compared with 6.4 for Hong Kong).

How did Kuwait get to this point and what was the role of the state?

This type of development started in the 1950s, when the state became the primary agent of urban growth and social change: Now that urban development and public welfare were entirely funded by oil revenues, the state became the primary agent of urban growth and social change. The general public was not involved in how their city was transformed or how their lives changed after 1950 (…) (Al-Nakib, 2016).

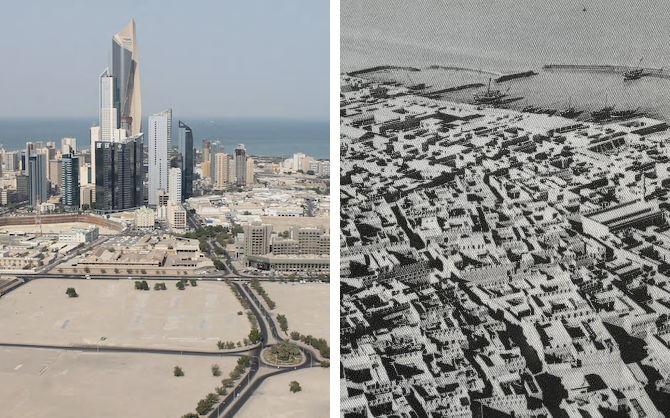

With the discovery of oil, Kuwait has undergone a transformative urban boom from a small Arab maritime town to a modern-day metropolis in less than half a century. At the time Kuwaitis thought they were building a positive legacy: a strong welfare system, better wealth distribution, better infrastructure – a modern city. However, inherent within this legacy were latent problems, the scale of which have only now been discovered. The table below introduces the key factors influencing the strong role of the state in Kuwait’s urban growth: (1) resource availability, (2) a strong welfare state linked to citizenship, and (3) urban planning.

| Resource availability (land and oil) | Newfound wealth in the 1950s and an opportunity to transform and grow | Consequences: Demolished historical town; Different opportunities to citizens and non-citizens; Motorised and urban sprawl growth; Negative impact on health and the environment |

| Citizenship (welfare state) | Welfare provisions and sharing of the wealth among the citizens: Public housing (dominantly villa types) | |

| Urban planning | A first rational masterplan with definition of the area of expansion, development of an efficient road system, and a strict land use zoning system with lack of mixed use |

In terms of resources (1), oil and land availability have directed urban development, with old Kuwait being demolished in the 1950s to create a modern city, and with the state investing in car-centric infrastructure from the beginning. Roads were at the core of the new plan, seen as the skeleton for the development of the current urban area (i.e. its suburban characteristics, and self-sustaining character in terms of schools and amenities). With the sudden and massive influx of oil revenues, a strong welfare system (2) was established to distribute the wealth among Kuwaiti citizens and improve their quality of life, a component of which was the provision of single-family housing to Kuwaitis. Finally, there was urban planning (3). The first masterplan was created in 1952 to translate these new welfare provisions into physical reality. Strict land use zoning with lower levels of mixed use in the dominant residential areas were introduced. Though over time a series of new master plans were created to accommodate the growth in population, all used similar planning principles to those implemented through the first blueprint.

The combination of all these factors promoted urban sprawl growth, long commuting distances, and high levels of motorisation and traffic congestion, with considerable negative impacts on health and the environment. In order to address traffic congestion and keep vehicles moving, the state has been investing in extending road infrastructure with the creation of double-decker highways. Other factors such as historical events and cultural or climate factors, though not explored here, also help explain urban development patterns. That were borne out of the neighbourhoods they built and lifestyle that was created.

According to a 2019 United Nations study, Kuwait’s national population is increasing rapidly and expected to increase by 50% by 2100. Accommodating this growth highlights the urgent need to change the current path of urban development and adapt to a more sustainable approach, a situation that faces many other GCC cities. According to the International Energy Agency, the Middle East, with 3% of the world’s population, accounts for 4% of the world’s total energy consumption and 7% of the global residential energetic consumption. Conversely Asia, with 52% of the world’s population, consumes only 35% of global energy and accounts for a mere 25% of total household consumption (values accurate as of 2015). This comparison illustrates, at a global level, the consequences of the legacy of urban policies developed due to land and oil availability in Kuwait and other GCC states.

As Kuwait’s situation today is obviously a result of the state’s adherence to a particular approach to urban planning, in order to avoid the pitfalls of further repetition, it seems vital for policymakers to institute wholesale changes to facilitate greater energy efficiency and sustainability. This may call for the rethinking of modern Kuwait at the metropolitan and neighbourhood scale, through the exploration of some of the elements, including its compact and dense design, that made old Kuwait a more walkable, climate-appropriate and culturally adaptable environment.

This blog post was based on research conducted as part of the Kuwait Programme project ‘Resource Urbanism‘, for which Alexandra Gomes was Research Officer.

This is part of a series emerging from a workshop on ‘Heritage and National Identity Construction in the Gulf’ held at LSE on 5–6 December 2019. Read the introduction here, and see the other pieces below.

In this series:

- Introduction by Courtney Freer

- Souvenir Sovereignty in Qatar by Suzi Mirgani

- Examining Kuwait National Museum by Sundus Alrashid

- Museums as Political Institutions of National Identity Reproduction: Are Gulf States an Exception? by İdil Akıncı

- The New Populist Nationalism in Saudi Arabia: Imagined Utopia by Royal Decree by Madawi Al-Rasheed

- Heritage and Sectarianism in Bahrain by Thomas Fibiger

- Dubai Expo 2020 and Ancient Mercantile Heritage by Robert Mogielnicki

- Managing UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Saudi Arabia: Contribution and Future Directions by Abdulelah Al-Tokhais

- Finding Mariam: the Invisible Woman in National Heritage Mythology by Alanoud Al-Sharekh

- Cultural Attendance: Attracting the Crowds to Museums in Saudi Arabia by Maha al-Senan

- Religion and Heritage in the Gulf: Significant in its Absence? by Courtney Freer

- Historical Archaeology in the Gulf by Robert Carter

- Militarised Nationalism in the Gulf Monarchies: Crafting the Heritage of Tomorrow by Eleonora Ardemagni

- The Practice of Heritage in the Northern United Arab Emirates by Matthew MacLean

- Displaying the Nation in Museum Exhibitions in Qatar by Alexandra Bounia

- Implicit and Explicit Cultural Policies in Qatar: Contemporary Art Production and Censorship by Serena Iervolino

- The UAE State ‘Rebirthing’ of Motherhood: Who is birthing who? by Rima Sabban

1 Comments