by Geoffrey Martin

One of the most serious challenges for Kuwait’s ‘Vision 2035’ series of economic reforms is the transformation of its oil dependent economy to a more dynamic private sector-led one. In the current system, public and private companies run on monopolies, subsidies, and a general lack of competition. Very rarely are employees in white collar jobs – national or foreign born – fired; absenteeism and inefficiency are rife; and workloads are incredibly light (some local reports say as little as two minutes a day). For years, I observed an office manager who worked a mere 40 minutes a day. Fascinatingly, the same person was pretending to work for 13 hours. It seems that many employees publicly display authority and knowledge on tasks they do not do; even when they know others are aware of this. Do people in oil states think they are lazy, or has this classification been unfairly applied by scholars of rentier state theory? Academic work on the motivations and work ethic of people in rentier states (like Kuwait) is scant, even though this is a very common topic of conversation in public and private life.

The issue of laziness and productivity strikes at the heart of work life anywhere else where economic incentives and employment may not be linked. The costs to the economy are stark. According to Al-Seyassah newspaper, in the first half of 2014 there were 1,084,000 sick or absentee days in the government sector (there are approximately 400,000 civil servants in the workforce). According to the World Bank, Kuwait was ranked 97 out of 190 countries in 2018 (down from 96) for ‘ease of doing business’. While one could emphasise the implications of this in terms of financial loss or (lack of) future economic development, as one Kuwaiti interlocutor noted,

‘Perhaps even more terrifying is the potential psychological damage someone who attends work may suffer, with almost no chance of real productivity or dignity. It may cost more for people to show up then stay home to get their pay cheques.’

These are not unique revelations for those studying rentierism. Notable scholars like Hossein Mahdavy, Hazem Beblawi, and Giacomo Luciani have argued that resource booms induce a ‘rentier mentality’; a myopia or sloth that comes from not having any economic incentive to work. As MaryAnn Tétreault once said, ‘the recipient is morally defective’, essentially selling their integrity, citizenship, and principles for a ‘plum job…The lazy and shiftless get government jobs and the economy staggers under their dead weight’. The rentier economy, according to such scholars, has normative implications for its citizens.

Despite widespread use, these ‘mentalities’ remain more of a fable rather than a product of empirical observations. In practice, these often-cited claims are inaccurately directed solely at nationals, while foreigners working in the country are often treated as immune (if not simply ignored), which has its own orientalist connotations.

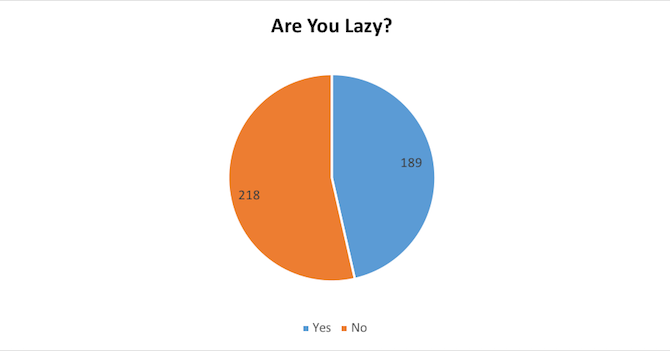

To start a discussion into the roots of the rentier mentality, which I frame as cultural rather than politico-economic, I conducted a survey between April and November 2018. I distributed the survey to Kuwait University, two private universities, and two national banks. I collected a total of 414 responses, from 165 male and 247 female respondents. For starters, I simply asked, ‘Are you lazy?’ to see if respondents would admit to not working. Out of 414 responses, 189 respondents admitted to being lazy in general, while 218 said they were not.

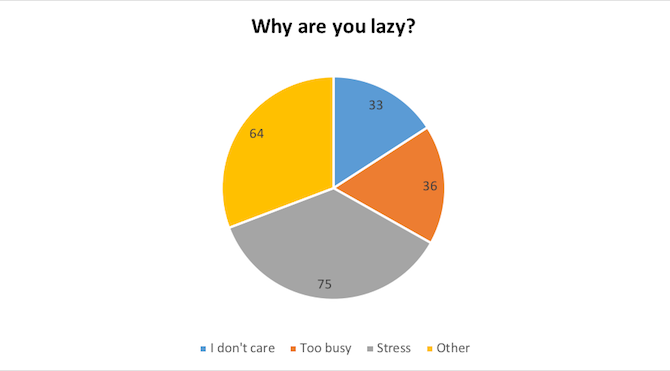

In the next question I simply asked the reasons why respondents were lazy. In this case, 144 respondents (note the difference from the previous respondents) stated they were not lazy, while the other 208 responded that they simply did not care, were too busy, or were too stressed to work effectively.

Some of the surveyed chose to comment on this question. The responses were overwhelmingly about a lack of motivation:

Life has a very boring and not very versatile routine. As one glorious man once said: life is hard; the only easy day was yesterday

It’s hard to be motivated when so many people around are lazy and me [I am] doing the work means [meaning] they can be even lazier

Tellingly, not one respondent noted that the salary was insufficient to justify more effort. There was also no mention of a lack of tasks to be done in their job (a common problem in Kuwait), or that respondents simply enjoyed working. It was clear from talking to some of the respondents after the survey that many people, especially those who marked themselves as ‘too busy’, prioritised their social life, and that work was simply an inconvenience.

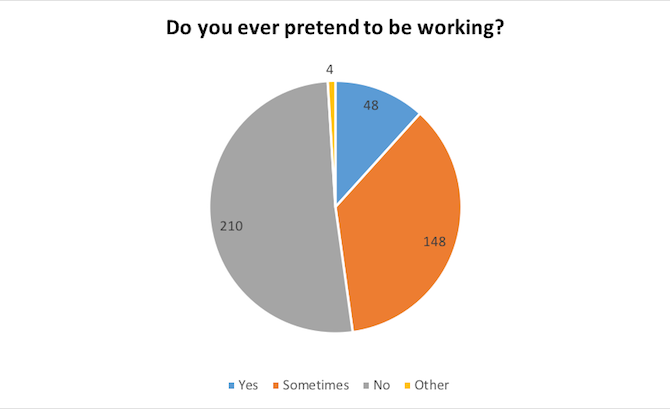

I next tested to see if the surveyed were self-aware about their work habits, and if they ever pretended to work. While 210 respondents said they did not pretend, 196 agreed to pretending generally, or pretending to work some of the time.

I then asked why a respondent might pretend to work. The most common answers tended to mention avoiding work or other people, or keeping an image:

To avoid things or people I don’t want to deal with

To avoid having someone yell at me

Because I don’t want to get yelled at, or people might think I’m lazy

Fake it until you make it

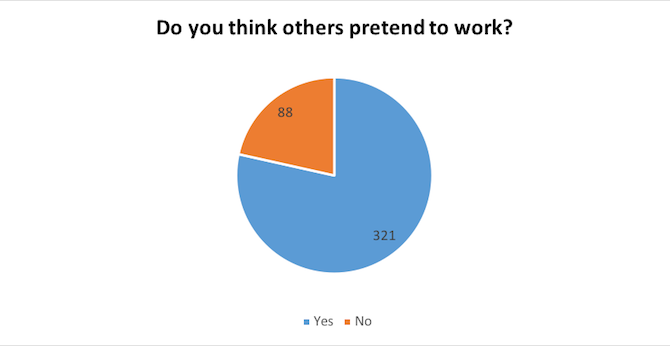

Flipping the question around, I asked respondents if they thought others pretended to work.

Asking why people pretend, many comments had the same themes noted when answering for themselves:

They don’t care about the type of work they have to do, or they are too demotivated

We all have an image (we) want others to believe

Because they like to hide behind a facade or a charade to conceal their disappointment at reality (which is also life)

They can get away with doing it and still get paid. There are no real repercussions

Because they have nothing to do in their sick boring lives

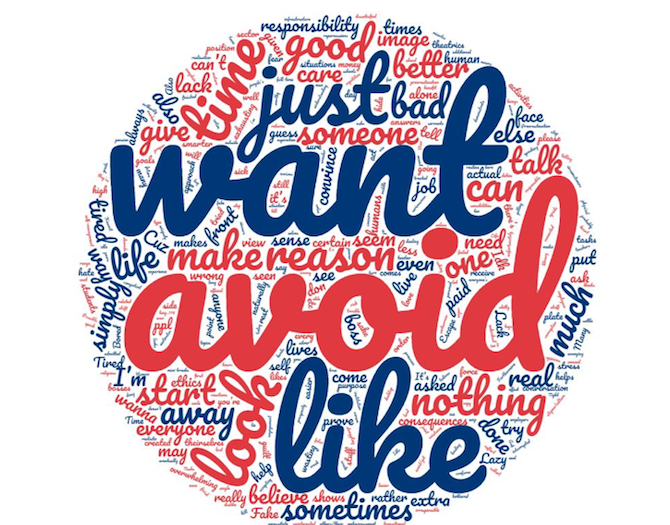

What were the root causes of inefficiency? Perhaps this is best visualised by looking at the words people in the survey used.

The word cloud illustrates what I call the ‘want/avoid paradox’. Respondents seemed to have a personal struggle to maintain an image and note their own work ethic, wanting to seem productive in the survey. Yet respondents did not seem to have a lot of self-awareness of what constituted their own ‘work’. And while they were disparaging toward how others acted, the majority did not reflect on their personal work ethic. Again, not a single person mentioned how the job itself brought benefits to their lives. They ‘wanted’ to work, while they were simply ‘avoiding’ it.

Perhaps of equal significance is the consistency of the findings across Kuwaiti and non-Kuwaiti residents in terms of self-awareness. Non-nationals, who made up 35 percent of the sample, shared the same opinions yet came from a variety of countries and occupations, and had spent different amounts of time in the country, although most were middle class. None blamed laziness solely on Kuwaitis, a common slur among expatriates in public life, and no respondent denigrated specific political factions/sects, public officials, or the government in general.

These results raise fundamental questions about expatriates’ role in Kuwait. As a recent path breaking research project from Batul Sadliwala noted, ‘scholarly discourses about the experiences of noncitizens living and working in the GCC rely overwhelmingly on narratives of socio-political exclusion and economic exploitation.’ This ‘often obscures the multifaceted nature of Gulf residents’ everyday interactions with one another’. This finding falls in line with work by Neha Vora and Natalie Koch, who challenge overdeterminism in Gulf expatriate experiences in the UAE.

These individual effects are also formative of Kuwait’s recent political climate. Calls to reform the inefficiency of Kuwaiti workplaces were centre stage in the Orange Movement protests in 2006 and Dignity of the Nation marches in 2013. Various demands by different groups included creating job opportunities, not simply pay checks, and encouraging entrepreneurship by cutting bureaucratic red tape. But this survey illustrates a wide difference in the awareness of people about what may be realistic. The problem for any government in translating demands for economic reform is creating actionable policy. Without people being aware of their own work ethic, one-size-fits-all policy changes are far less effective, and government reforms are untranslatable. Perhaps, being lazy is not really a choice.

I discussed the issue of unproductivity with various residents. For one group of Kuwaitis, a key reason for this mentality was state policy. They argued that the state treats people like children, creating an ‘insane dependency’, which fits the rentier bargain thesis. For example, Kuwaitis in university are banned from working part-time jobs and must live at home until they are married. Government jobs are allocated in terms of availability, not qualification, meaning most citizens work in positions they are not qualified for, and only begrudgingly undertake. As one said, ‘There isn’t recognition of people working hard, for government jobs there is a “punch in and punch out” mentality’.

The same interviewee also blamed individuals, saying that ‘people are simply too comfortable and there is a form of affluence that goes against hard work’. Another source indicated that ‘when factoring in a lack of belonging, it is clear how there would be a lack of motivation’. As Hazem Beblawi once wrote, rentierism is ‘more of a social function than an economic category’ and for individuals ‘resides in the lack or absence of a productive outlook in his [or her] behavior’ (pp. 86, 88). One last interviewee had a historical explanation, saying that,

‘Kuwaitis are doing the same thing they have always historically done: survive! The only difference is before it was pearl diving and low customs to get some money, and now it’s be lazy to avoid trouble and seemingly conform to a societally enforced image by “working”.’

There are many questions to answer, but overall the results of the survey fit with a conceptualisation of rentier mentality that accounts for culture, instead of just political economic concerns. This also moves away from treating the study of psychology as orientalist by allowing people to speak for themselves, instead of simply accusing them of damaging the fabric of their societies. Being lazy is not in ‘the Kuwaiti DNA’ as one respondent noted, nor is it something that revolves around personal choice or state policy in isolation.

In fairness to Mary Ann Tétreault, it might be appropriate to edit this content. Martin quotes her as if she believes that citizens of rentier states are ‘morally defective.’ That’s wrong. The Tétreault quote is pulled from a section of her book discussing the *myths* of the rentier state. She’s saying that it’s a *myth* that citizens are morally defective, and we should understand such myths as “weapons in the war for differential accumulation.” (p. 53)