by Alenka Prvinšek Persoglio

A State is defined in international law as a territory with a permanent population, ruled by a government with a capacity to enter into relations with other states. States are responsible for protecting the interests of their citizens in accordance with obligations that derive from international law, as well as their own constitutions and laws.

One of the basic obligations of a state is to ensure that every person under its jurisdiction is recognised as a person before the law (Article 6 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights). In principle this recognition is independent of the person’s appearance on any register. In practice, one of the most important steps towards ensuring this recognition and equal protection of the law is the registration of the birth of every person born in the territory of the state. The right to birth registration is a fundamental human right of every child (Article 7 of the UN Convention on the Right of the Child) and is not subject to the discretion of the State.

Still, it is estimated that there are more than 1 billion people under the age of five globally who do not appear in national records of civil status. This means that legally, they do not exist, which presents them with significant challenges when it comes to proving their legal entitlements, and they can be prevented from claiming the protection of the state of citizenship or residence. For children, this creates obstacles to enrollment in the education system, access to health services including immunisation. Stateless children might also be at higher risk of becoming victims of human trafficking and for young girls, there is a risk of forced marriage. Adults whose births haven’t been registered are excluded from state health services and the protection of their labour rights. For specific vulnerable groups who enjoy special protection – persons with disabilities or indigenous peoples who are entitled to special protection by the instruments of international (UN)law – this means the denial of their existence and their legal entitlements.

In recognition of the significance of this gap, Target 16.9 of the SDGs stipulates that by 2030, every person in the world should have a legal identity, including birth registration. However, “legal identity” is an expression that is not defined in international law.

At the national level, legal identity has different definitions, which are covered by different laws. These are likely to include a civil code or other laws that regulate the registration of civil status and names (including births and deaths registration acts in the common law countries), family law, citizenship law, laws on identity documents or personal identity numbers, among others. But the initial point for establishing the identity of a person is registration immediately after birth by the relevant state authority. Birth registration also determines a person’s access to a nationality either by the fact of birth in a particular state (jus soli), or by descent (jus sanguinis). As noted in June 2015 by Carol Batchelor, the Director of International Protection Division of UNHCR,“legal identity can only come through national measures based on Rule of Law principles”.

There are no available statistics on the number of adults that remain without legal identity; either because they have never been registered, or because the evidence of registration has been lost, destroyed or confiscated.

In those cases where civil registration records have been destroyed – through war or disaster – states need the legislation and the capacity to enable them to establish or re-establish the identity of their citizens. Among those states that belong to the legal system of continental Europe, civil registration laws generally provide rules and procedures to enable restoration of identity. This includes transcriptions of the original civil status records into copies of the register stored in a different location and regularly updated (whether in paper or digital form). Among countries in Africa within this tradition, Ivory Coast issued a presidential decision on the reconstruction of civil status registers following their destruction during conflict.

A specific challenge is posed by the practice of self-declared independent territories, which are not internationally recognised by any state. Legally, they remain under the sovereignty of the state from which they declared secession, meaning they do not have their own law to regulate civil registration. Such a case is Somaliland, which according to international law is part of Somalia, a country with very low rates of birth registration.

One solution to overcome this issue might be the application of general principles of international law within self-proclaimed territories. The rights of the child as stipulated in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child – with a specific imperative regarding the obligation to register every child immediately after the birth – should form the guiding principles in those territories that do not enjoy international recognition. The mere fact of the recognition of birth of every child by its registration in the data under the authority of recognised or non-recognised entity should become a universal standard.

In other cases, children who are born to parents with known citizenship, but outside the state of the parents’ nationality, may end up stateless if their births are not registered by the state of birth. During an assessment for UNICEF in 2018, the Ministry of the Interior in Niger told me that there had been cases where the Malian authorities refused to register the births of children with Nigerian parents, leaving them at risk of recognition of neither Malian nor Nigerian nationality. Problems like this may be resolved in the form of bilateral agreement, with the appointment of a commission composed of civil servants responsible for resolving day-to-day issues. A precondition should be an appropriate legal basis in respective law, as well as awareness-raising among respective populations about the consequences of irregular movements over state borders.

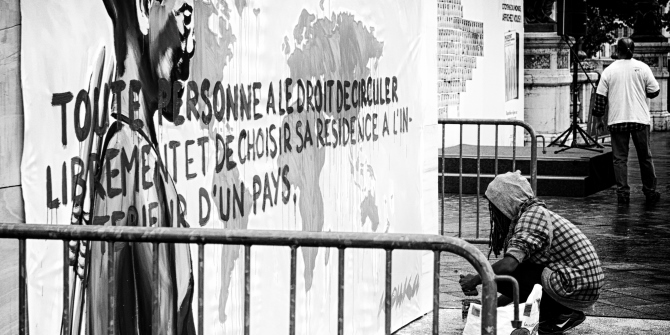

The cross-border movement of persons, voluntary or forced, regular or irregular, requires a high degree of cooperation among states with respect to the identity of persons, particularly (though not only) if they do not possess any official identity documents. The role of consular services in providing assistance to their citizens by consular registration of vital events (especially births and deaths) is important. But this service depends on the authorities of the host state first providing formal notification of birth or death.

To understand these systems, it is important to first understand the rules for the legalisation of documents, or the procedures for acceptance of a foreign public document that certifies a civil status fact within the domestic legal system. Here, bilateral agreements are the most effective, concluded usually between the countries of origin and countries of destination, particularly in cases of labour emigration. These agreements are negotiated with the objective of removing lengthy procedures on authentication and legalisation (for instance, in the case of transfer of certificates of birth, marriage or death to the country of origin for the purpose of registration).

The most renowned legal instrument of this kind is the 1961 Hague Convention Abolishing the Requirement of Legalisation for Foreign Public Documents (the Apostille Convention), to which 117 states are contracting parties. For those States that whose national systems of civil registration are highly reliable, the Convention foresees the possibility of online certification of legalisation and authorisation. Separately, a new European Union regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/1191) that aims to reduce costs and shorten lengthy procedures for mutual recognition of a range of public documents came into effect on 16 February 2019, and applies to certificates of birth, death, marriage, divorce, name, citizenship, and other related statuses. An online tool provides further help with understanding these rules in other EU member states.

It is important that the different elements of legal identity are entitled to protection as part of a person’s right to privacy and data protection. Identity belongs to persons and not to the state. The Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights also indicate that private sector companies involved in identity management share this obligation.

Finally, a necessary precondition for an effective service for civil registration and legal identity is not only an effective legal framework but also well-trained staff. Some states have developed training systems at the national level that provide theoretical and practical knowledge, including the relevant international treaties, family law, citizenship, data protection, archives, statistics and international cooperation. Such training should be mandatory for all civil servants who deal with civil registration, including consular services staff.

Alenka Prvinšek Persoglio is former chair of the Committee of Experts on Nationality in Council of Europe, and former Senior Policy Advisor for the International Centre for Migration Policy Development.

Alenka Prvinšek Persoglio is former chair of the Committee of Experts on Nationality in Council of Europe, and former Senior Policy Advisor for the International Centre for Migration Policy Development.

This blog post and the others in the series are based on presentations during a workshop convened by the MEC on 1 March 2019 discussing statelessness and legal identity in the context of migration.

In this series:

- Preventing Statelessness among Migrants in North Africa and their Children: Birth registration and ‘legal identity’ by Bronwen Manby

- State Obligation to Establish Legal Identity in Comparative Perspective by Alenka Prvinšek Persoglio

- Civil Registration and Legal Identity in Humanitarian Settings by Ann Livingston

- Preventing Statelessness among Undocumented Migrants: The role of the International Organization for Migration by Anne Althaus & Laura Parker

- From Birth Registration to Confirmation of Citizenship: Is the UK process the model to aspire to? by Elan Schwarz and Brianna Gomez

- What is the Fuss over the UN’s Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration? by Elspeth Guild

- When Identity Documents and Registration Produce Exclusion: Lessons from Rohingya Experiences in Myanmar by Natalie Brinham

- Consular Protection, Legal Identity and Migrants’ Rights: Time for Convergence? by Stefanie Grant

- Obstacles to Accessing Civil Registration and Identification: NRC’s Field Experiences with Displaced Persons by Fernando de Medina-Rosales

- Defining Identity and Identifying Migrants in the Global Compact for Migration by Tendayi Bloom