by Anne Althaus & Laura Parker

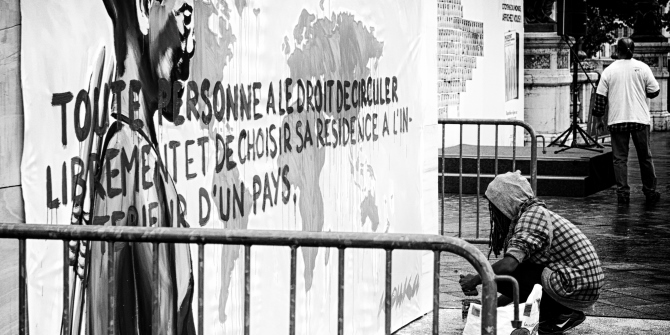

The Relationship Between Statelessness and Migration

Although most stateless people are not migrants, there is an important nexus between migration and statelessness. This is reflected in recent international processes such as the Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Compact for Migration, which push for the issue of statelessness and legal identity to be resolved by States along with migration matters.

Statelessness can be a cause of migration when people move due to unremitting discrimination and exclusion from basic rights and services. In such cases, statelessness represents a push-factor. In extreme cases, entire groups of persons are expelled or leave due to marginalisation, violence and threats against them.

However, even more often, statelessness can be a consequence of migration. Migrants – either international or internal – may struggle to prove their civil status and, consequently, their nationality when they have difficulties in keeping or obtaining documents such as marriage or birth certificates, and other legal identity documents. Such documents, especially when issued via late procedures, may rely on witness testimony from the community of origin or birthplace. This is often harder for migrants to access, due to lost ties and practical barriers to communication over time. Even where frameworks for universal birth registration are in place, officials may refuse to register the birth of migrant children, whether the parents’ migratory situation is regular or not, based on the belief that this confers nationality – even in cases when it does not. Migrants – including internally displaced persons – may leave documents behind when fleeing, lose them during the journey, or see them confiscated by smugglers or corrupt officials. Records may be destroyed by conflict or disaster, complicating access to proof of identity. These practical difficulties may then put persons on the move at risk of being unable to prove their nationality, particularly when the situation becomes protracted.

Over generations, descendants of migrants may lose ties with their ancestors’ place of origin, without necessarily fulfilling citizenship requirements of their country of residence, i.e. the country where they are born and live. Statelessness among these “historic migrants” who are not themselves on the move, yet who are universally perceived as foreigners, is not uncommon. Even contemporary migrants can be affected by legal loopholes: a few countries have laws providing for automatic loss of nationality after a certain period abroad, without safeguards against statelessness ensuring the migrant has acquired the nationality of their new host country.

Because of the close nexus between statelessness and migration, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) seeks to contribute to the fight against that plight.

Migrants at Risk

Migrants at risk of statelessness are those who are facing issues in proving their nationality, whether for administrative or legal reasons as laid out above.

Children of migrants born in transit or in the destination country are a particular at-risk group, as they can face issues in accessing legal identity documentation due to barriers to birth registration or conflicts of applicable domestic laws. Some children of migrant parents are exposed to risks of statelessness given inequalities between men and women relating to the conferral of nationality upon children born abroad in some national legislations.

Nomadic and indigenous populations may often be unable to substantiate entitlement to nationality in all the countries with which they may have ties. Even internal migrants from a minority group or border region may be perceived as outsiders in their host communities and denied recognition.

Irregular migrants and their children can be at higher risk of becoming stateless because they often encounter even greater issues with possessing the requisite legal identity documentation. They are therefore, in addition, at tremendous risk of indefinite or arbitrary detention. Furthermore, for fear of detention and deportation, the registration of the births of their children in the country of residence may appear impossible. Some States refuse to register the birth of irregular migrants’ children, leaving them at risk of statelessness.

The IOM’s Role

While UNHCR has the mandate for statelessness within the UN system, the IOM contributes both to providing assistance to stateless migrants and to preventing migrants from becoming stateless in the first place. IOM is particularly concerned with migrants stranded in another country without documentation, unaccompanied migrant children, migrants in detention, victims of trafficking, second generation migrants and internally displaced persons. The IOM seeks to assist those migrants where they are, because they face significant problems daily due to their lack of civil status documentation.

Facilitation of consular assistance and access to documentation — The IOM seeks to assist migrants in obtaining critical civil status documentation and/or to prove their nationality, which is generally critical for obtaining travel documentation. In order to assist migrants in obtaining documentation, the IOM often liaises extensively with consular authorities, whether in emergency contexts or not. Processes for obtaining documents can be quite daunting or simply impossible for migrants alone, as they often involve complex procedures, burdensome and expensive travel, fees, and sometimes additional obstacles such as corruption, extortion and discrimination.

The IOM’s objective is to ensure rapid access to consular services for migrants in need. To this end, the IOM strives to increase access to consular services and their geographical coverage. This is achieved, in part, by financial support for consular missions, but also includes capacity building and logistical support.

For example, the IOM supports migrants in Libya to connect with their respective consular authorities on the Libyan territory, abroad or through online consular services. It also supports consular authorities with gaining access to their nationals in or outside of detention and referring cases where necessary. Access to consular authorities is instrumental for migrants who wish to voluntarily return to their country of origin through the IOM’s Voluntary Humanitarian Returns programme (VHR), particularly for those in detention who have no other means of external contact. Irregular migrants in Libya often lack civil status documentation and travel documents. Contact with consular authorities is particularly trying in the Libyan context, since many embassies and consulates are not present on the Libyan territory itself, but rather in neighbouring countries. IOM assists with ensuring that migrants understand the complex procedures and can prove their nationality, so as to ultimately obtain the necessary travel documentation in order to return home, when they wish to do so. IOM can assist migrants to obtain testimonies — for example from community leaders present on the Libyan territory — that are often requested by consular authorities as corroborating evidence of an individual’s nationality, to enable the issuance of travel documents. The IOM has been recommending that consular authorities deploy more human resources and rethink their procedures for determining proof of nationality or permanent residence, to expedite the delivery of the necessary documents. It has also supported consular visits to enable countries wishing to send a mission to transit countries such as Niger to provide travel documents to their nationals and, at the same time, to establish mechanisms for the issuance of travel documents.

Undocumented migrant children, while not necessarily stateless, are at greater risk of statelessness, trafficking, child labour, child marriage, illegal adoption, sexual exploitation and recruitment into armed forces and groups. The IOM assists unaccompanied migrant children with family tracing in order to locate their parents, establish where they came from, and recover identity and other documents.

In North Africa, the IOM has deployed efforts in Tunisia and Libya to improve the best interest determination procedure for unaccompanied migrant children and to help those children in obtaining the necessary documentation to access their rights and local services, return home, or to reunite with family abroad – according to their best interest. In Libya, the IOM has conducted trainings for consular authorities on the best interest assessment and best interest determination processes, since consular authorities engage in these as well as in family tracing. It has also assisted migrants with registering their children at birth, and has raised awareness on the need to go beyond a mere birth notification issued by a healthcare provider in order to ensure the child’s access to rights and services.

Studies and collaboration with governments — The IOM has engaged in studies with UNHCR to evaluate the state of national laws regarding nationality and migration and their impact on statelessness. Results are often shared with the public, or are used as a baseline for providing assistance to States in strengthening domestic legislation. It also conducts and supports workshops and trainings on policy matters and international law obligations in areas relating to statelessness.

Partnerships and inter-agency work — The IOM supports the #IBELONG campaign to eradicate statelessness by 2024, and is a part of the UNICEF–UNHCR-led coalition on every child’s right to a nationality. Furthermore, the IOM is part of the Inter-Agency Working Group on Statelessness, and has welcomed the inclusion of Target 16.9 in the Sustainable Development Goals, which promotes providing legal identity for all, including birth registration, by 2030.

Recommendations

Preventing statelessness among migrants requires a coordinated, multi-pronged approach on both a practical front and with regard to legal reform.

- States can ensure that their consular authorities are providing adequate assistance to at-risk persons in need of confirmation of their status as nationals – whether for issuing emergency travel documentation, or, ideally, proof of identity that will serve migrants regardless of their intent to remain, return or travel onwards. That requires that States ensure their consular authorities have sufficient capacities, including adequately trained human resources, and are physically accessible. It also supposes that measures are taken to remove, as much as possible, barriers to accessing documentation, by developing links with migrant communities, regularly visiting such communities and taking on the burden of translating of documents. IOM stands ready to support with these efforts. In Libya, the African Union – European Union – United Nations tripartite taskforce (AU-EU-UN tripartite taskforce) formally acknowledged and called upon African countries to make their consular services available to migrants in Libya.

- Consular authorities should be involved and active not only in cases of detention of migrants, expulsion, or return, but also to assist migrants in developing a dignified life wherever they may need support, to get a clear insight into the living conditions and protection issues of their nationals, and to strengthen relations with host countries in order to find sustainable solutions. More systemic support is needed to strengthen consular procedures, enhance coordination between capitals, embassies and consulates, and to strengthen cooperation among States. Consular visits in a transit or destination State can be essential for assisting migrants in vulnerable situations and facilitating their recognition and documentation as nationals. The IOM seeks to increasingly advocate for adherence to official and simplified procedures for determining nationality or permanent residence based on domestic nationality law, immigration laws or other relevant legislation.

- The IOM also encourages States to further engage in education campaigns about the requirement and benefits of birth registration and to increase the capacities of civil registration authorities, in the receiving country and through consular authorities, for both regular and irregular migrants. Barriers to birth registration of the latter, whether by law or in practice, should be lifted. Only with such measures, and more, will we see the number of people at risk of statelessness decrease, which is part of the fight against statelessness. Finally, the IOM, together with UNHCR, encourages countries to review their laws such that nationals are protected against loss of nationality on account of residence abroad, where doing so would render them stateless.

The seriousness of the risks of statelessness for many migrants and the potential for both “enduring and multi-generational” disastrous effects cannot be stressed enough. The IOM remains keen to leverage its specific role and expertise to further the common struggle against statelessness.

Anne Althaus specialises in human rights and international criminal law and has been working as a migration law officer within the International Migration Law (IML) Unit of the IOM since 2013. The IML Unit is responsible for the promotion of the international legal standards governing migration and providing protection of the rights of migrants. Anne holds a LL.M. in Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law from the Academy of Human Rights, Geneva.

Anne Althaus specialises in human rights and international criminal law and has been working as a migration law officer within the International Migration Law (IML) Unit of the IOM since 2013. The IML Unit is responsible for the promotion of the international legal standards governing migration and providing protection of the rights of migrants. Anne holds a LL.M. in Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law from the Academy of Human Rights, Geneva.

Laura Parker is a human rights professional, with experience in the fields of statelessness, legal identity documentation, forced migration and management of legal aid programmes. She has worked for civil society organisations and UNHCR in Africa and Latin America, and currently heads the protection team at IOM Mauritania. She tweets at @Laurafromlondon

This blog post and the others in the series are based on presentations during a workshop convened by the MEC on 1 March 2019 discussing statelessness and legal identity in the context of migration. @BronwenManby

In this series:

- Preventing Statelessness among Migrants in North Africa and their Children: Birth registration and ‘legal identity’ by Bronwen Manby

- State Obligation to Establish Legal Identity in Comparative Perspective by Alenka Prvinšek Persoglio

- Civil Registration and Legal Identity in Humanitarian Settings by Ann Livingston

- Preventing Statelessness among Undocumented Migrants: The role of the International Organization for Migration by Anne Althaus & Laura Parker

- From Birth Registration to Confirmation of Citizenship: Is the UK process the model to aspire to? by Elan Schwarz and Brianna Gomez

- What is the Fuss over the UN’s Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration? by Elspeth Guild

- When Identity Documents and Registration Produce Exclusion: Lessons from Rohingya Experiences in Myanmar by Natalie Brinham

- Consular Protection, Legal Identity and Migrants’ Rights: Time for Convergence? by Stefanie Grant

- Obstacles to Accessing Civil Registration and Identification: NRC’s Field Experiences with Displaced Persons by Fernando de Medina-Rosales

- Defining Identity and Identifying Migrants in the Global Compact for Migration by Tendayi Bloom