by Thomas Bernhardt

The production of goods and services is increasingly spread across different countries and organised in global value chains (GVCs). These GVCs are based on cross-border information flows, investment and trade. When, at the turn of the millennium, North African countries entered into trade-liberalising Association Agreements (AAs) with the European Union (EU) – which Tunisia did in 1998, Morocco in 2000, and Egypt in 2005 – they expected to reap economic benefits such as attracting foreign investment, penetrating new export markets, and joining and upgrading in value chains serving the European market.

Trade data can be used to examine whether these benefits have materialised. Here, the focus will be on these three countries and on two sectors, namely apparel and automotive. These are of particular importance to these countries, contributing considerably to output, employment and trade with the EU. This blog investigates to what extent Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia have achieved export diversification and economic upgrading in EU-bound apparel and automotive GVCs since signing AAs with the EU.

Trade dynamics

After entering into AAs, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia indeed intensified their commercial linkages with the EU and overall trade grew two- to threefold. Today, all three countries count the EU as their largest trading partner. However, trade dynamics have not been homogeneous across sectors. While Egypt and Morocco managed to somewhat expand their apparel exports to the EU, Tunisia’s declined by 10 percent. All three countries fell in the ranking of the EU’s top apparel sourcing countries, losing out in particular to Asian exporters.

By contrast, automotive exports exploded, multiplying by a factor of 50 to 60 in the cases of Egypt and Morocco while tripling in Tunisia. Morocco and Tunisia even turned their sectoral trade balance with the EU from to deficit to surplus. Despite of this, all three countries are still negligible players in the EU-bound automotive GVC as none of them has a market share of even only 1 percent. At the same time, Eastern European countries, notably the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia, have much more rapidly emerged as new key suppliers to the EU automotive industry.

Export diversification

Relying too much on a few export products and markets makes countries vulnerable against external shocks. Diversifying their country’s export basket and destinations, thus, is a common objective for policymakers. For the three countries of interest, a high degree of dependency on the EU can be noted. The EU accounts for almost a third of Egypt’s total external trade and for close to two thirds of Morocco’s and Tunisia’s.

Strikingly, since the AAs were signed, the EU lost in relative importance as a market for their apparel and automotive exports. Even as export values have been rising (often significantly), the EU’s share in the three countries’ total sectoral exports has declined (with the exception of Egypt’s automotive exports). This shows that there has been some diversification away from the EU which, however, still absorbs (often much) more than two thirds of the countries’ apparel and automotive exports (except for Egyptian garments).

Moreover, the three countries are strongly specialised in certain segments of the two GVCs. Their garment exports to the EU consist almost entirely of final apparel products whereas textiles and other intermediate products make up only a tiny proportion (except in Egypt). Similarly, their automotive exports are heavily concentrated in parts and components but include only very low values of assembled vehicles. The local backward and forward linkages in these value chains, hence, appear to be quite shallow. This has changed only little under the AAs. The only exception is Morocco’s automotive industry which in recent years has started to export passenger vehicles at significant scale so that they now make up 40 percent of their automotive exports to the EU (compared to just 1 percent in 2010).

For a more accurate and complete picture of diversification patterns and trends, the Hirschman-Herfindahl Index (HHI) is calculated. It is a measure of concentration and can help to determine the extent to which a country’s exports are diversified across different products and markets. The HHI takes values from 0 (diversified) to 1 (not diversified).

Table 1 reports the HHI values on export market and product diversification for the three countries in the two GVCs. It reveals that, generally speaking, the three countries’ apparel exports are more diversified, both across products and markets, than their automotive exports. One explanation for this difference is that the garments industry is more established and has a longer history in these countries, which has given them more time to broaden their product range and sales.

Table 1 also shows that, by and large, HHI values have been declining, indicating that the three countries have diversified their export structures in both the apparel and automotive GVCs under their respective EU-AA. Exceptions to this pattern are Egypt’s and Morocco’s automotive industries whose export baskets have become more concentrated. This is because wiring sets have emerged as dominant export items, accounting today for 51 percent of Morocco’s automotive exports to the EU and as much as 79 percent of Egypt’s.

| Export market diversification | Export product diversification | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVC | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 | |

| Egypt | Apparel | 0.348 | 0.286 | 0.182 | 0.110 | 0.087 | 0.086 |

| Automotive | 0.176 | 0.139 | 0.117 | 0.540 | 0.264 | 0.634 | |

| Morocco | Apparel | 0.214 | 0.202 | 0.187 | 0.040 | 0.032 | 0.028 |

| Automotive | 0.263 | 0.243 | 0.199 | 0.147 | 0.785 | 0.308 | |

| Tunisia | Apparel | 0.219 | 0.179 | 0.153 | 0.057 | 0.063 | 0.063 |

| Automotive | 0.346 | 0.185 | 0.227 | 0.510 | 0.483 | 0.437 | |

Economic upgrading

Integrating into GVCs brings the hope of economic upgrading to firms and, indeed, entire economies. There are also concerns, however, that countries are pushed and locked into low-value segments within GVCs. From the onset, economic upgrading has been a core topic in the GVC literature. It can be defined as the process by which economic actors – nations, firms and workers – move from low-value to relatively high-value activities in GVCs.

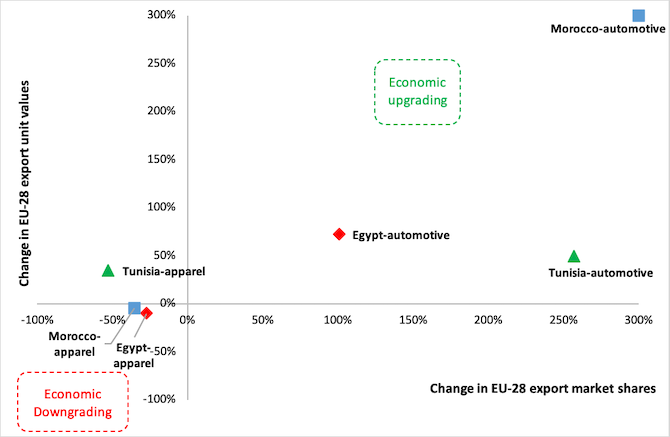

To operationalise this broad concept, a ‘parsimonious’ approach to measuring economic upgrading is adopted here, relying on two indicators: A country is said to have experienced economic upgrading in a given GVC if it increased both (1) its export unit values relative to the industry average, implying the production of higher-value products, and (2) its export market share, signalling international competitiveness. Conversely, a decline in both indicators is interpreted as economic downgrading. The performance of countries can then be depicted in 2×2 matrices where economic upgraders show up in the upper-right quadrant, downgraders in the lower-left quadrant, and ‘intermediate cases’ in the remaining two quadrants.

Using this method, Figure 1 is a graphical illustration of how the three countries performed in the EU-bound apparel and automotive GVCs since entering into AAs with the EU. It reveals an interesting pattern. All three countries are shown to have upgraded in the automotive GVC. That is, all three have increased both their share in the EU market and their export prices. In the apparel GVC, by contrast, Egypt and Morocco have experienced economic downgrading while Tunisia is classified as ‘intermediate case’, having increased its export unit values but lost market share.

Note: For better legibility, Morocco’s data point has been re-scaled. The real values are 2.269 percent and 2.201 percent.

This analysis does not say anything about the factors driving the observed performance. However, it is known that in the apparel GVC North African suppliers have suffered from the expiration of the multi-fibre agreement (MFA) in 2004 which enormously intensified competition from Asia. Meanwhile, thanks to their geographical proximity to Europe their automotive industries appear to have benefitted from increased outsourcing from Europe to neighbouring regions. Different policy initiatives, including industrial policies and setting up special economic zones, have also contributed to this outcome.

Concluding remarks and future research

Since the different AAs came into force, trade between the EU and Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia has grown rapidly. At the same time, however, the EU’s share in the countries’ total exports and imports has declined. This indicates that the AAs have not simply led to trade diversion but to real trade creation. Exporting to the EU, hence, appears to have supported the build-up of productive capabilities that helped to make inroads into other markets as well.

Yet, developments have not been entirely uniform across countries and sectors. While all three countries increased their automotive exports and imports with the EU, signalling an expanded participation in this GVC, in the apparel industry this is only true for Morocco. Similarly, the three countries have economically upgraded within the EU-bound automotive value chain but mostly downgraded in the apparel GVC. From an economic development perspective, moving out from a low-tech sector like apparel is not necessarily a bad thing, though, especially if the country is instead integrating into higher-tech GVCs such as automobiles.

By and large, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia have all managed to diversify their export baskets and markets in both the apparel and automotive GVCs. At the same time, however, their activities are still strongly concentrated in certain segments of the two GVCs (assembly of final garments and production of automotive parts and components, respectively). Only Morocco has recently moved into also exporting passenger vehicles, suggesting that some functional upgrading has occurred. Meanwhile, its exports – like those of Egypt and Tunisia – continue to be dominated by one product group, namely wiring sets, highlighting a degree of vulnerability against potential future demand or technology shocks.

More (especially qualitative and field) research is needed to corroborate (or rebut) our findings. Interviews can help to shed light on why European investors decided to invest or source from North African countries (or against it). Local companies could be surveyed about how they perceive the impact of the EU-AAs on their business. Our analysis also offers little in terms of explaining the observed performance patterns so future studies that investigate potential explanatory factors such as public policies, local firm capabilities and activities, lead firm behaviour, GVC governance, etc. would be useful. Finally, comparative analyses on peer countries would help to contextualise and better understand the findings for Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia.

The views expressed here are entirely those of the author; they should not be attributed to any former or current employer.

This is part of a series emerging from a workshop on ‘Mediterranean Production Networks and the Export Economies of North Africa‘ held at LSE on 17 January 2020. Read the introduction here, and see the other pieces below.

In this series:

- Introduction by Shamel Azmeh

- The Scandal of Seamless Linkages: Global Value Chains and Women Argan Oil Producers in Morocco by Kate Meagher

- Is Automation Stealing Manufacturing Jobs? Evidence from South Africa’s Apparel Industry by Jostein Hauge and Christian Parschau

- COVID-19, Digitalisation and Manufacturing-Led Development in African Countries by Karishma Banga

- Luxury Brands’ Roles in Pathways to Sustainable Growth: Prospects for Egypt’s Cotton Sector by Rachel Alexander

- Varieties of Digitalisation in Automotive Supply Chains and Upgrading Prospects of Supplier Firms by Merve Sancak

5 Comments