by Serena Iervolino

‘There are no cultural policies in Qatar’. Or so I was resolutely told by a colleague soon after joining UCL Qatar, an offshore campus of University College London in Qatar, in 2014. But is this statement accurate? In this article, I challenge this widespread misconception by viewing it through the lens of explicit and implicit cultural policies. Whilst this distinction has never been applied to a Gulf country before, it illuminates how Qatar governs its museum sector. More specifically, it sheds light on contemporary art production, curation and reception. How might a conservative state such as Qatar, keen to be known as an instigator of creativity, best manage contemporary art production (and its radical, irreverent and political tendencies), if not through implicit policies? I draw on research from the project, ‘Curating Contemporary Art in Conservative Societies and its Ethical Challenges: The Case of Qatar’, funded by King’s College London.

Qatar’s Implicit and Explicit Cultural Policies

Ahearne describes cultural policies as deliberate, strategic courses of action taken by any state to shape its vision and programme for culture. Nadia von Maltzahn adds that such policies include frameworks and tools to translate that vision on the ground. With regards to Lebanon, she also describes a general misconception about the absence of cultural policies, similar to my colleague’s claim about Qatar. In a country whose cultural sector represents a central domain of governmental action, however, this misconception appears baffling. Surely some deliberate, strategic courses of action must be in operation, even if not labelled ‘cultural policies’? The scepticism around the existence of cultural policies confirms the common myopic tendency to ignore ‘strategically interesting nexuses of culture and policy simply because they do not bear the appropriate labels or crop up in familiar administrative sectors’.

If one focuses only on policies explicitly labelled ‘cultural’ by the government and delivered by specialised art and cultural state agencies, such policies are indeed minimal in Qatar. They include Qatar’s Law No 2 on Antiquities (1980) focusing on ‘movable or immovable discoveries’, currently being updated. They also include Emiri Resolution No. 65 (2005), which established Qatar Museums Authority, later rebranded Qatar Museums (QM), and the Emiri Resolution No. 26 (2009) that replaced it. Led by a member of the royal family, Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad Al Thani, QM is the specialised agency responsible for administering Qatar’s public museum sector (Figure 1). Whilst QM sets apart a distinctive sector of ‘public’ policy action on museums, its operations are highly secretive as its long-term strategic plans, policy documents or measures of policy implementation (such as annual reports) have never been published.

A focus on explicit cultural policies overlooks Qatar’s implicit cultural policies: political strategies aiming to define and shape ‘the culture of the territory over which it presides (or on that of its adversary)’. These strategies identify a broader field of political action on a nation’s culture beyond a government’s official cultural administration, typically through other areas of public policy including foreign, media and educational policy.

Implicit Cultural Policies: Educational Strategies

Qatar’s policy measures in the field of education are especially important in art production, curation and dissemination, and particularly, the establishment of Qatar Foundation (QF). QF is a ‘private’, non-profit, parastate organisation and soft-power enclave that aims to support Qatar’s human development goals. These goals have been achieved through establishing branch campuses of international elite universities, including Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts in Qatar (VCUarts Qatar): a satellite campus of a top-ranking US arts school. Qatar’s decision to establish VCUarts Qatar was part of a deliberate course of action to support the state’s objectives in the museum sector – or, in other words, an implicit cultural policy.

Sheikha Al Mayassa has praised VCUarts Qatar for forming ‘new generations of young artists and designers who have enriched my country with creativity and innovation’. As revealed in interviews I conducted with actors in the museum/art ecosystem, VCUarts Qatar simultaneously fosters and regulates creativity and art-making. For instance, a recent graduate, interested in addressing religious, non-Muslim topics and iconographies, created a realistic painting of a religious subject. The artist was asked to keep the artwork in their studio and prohibited from displaying it at the school (interviewee 1). Nonetheless, the artist eagerly described this censorship not as a limitation but as a trigger for their creativity, manifested in their decision to embrace abstractionism to ‘work around the system’. Other interviewees referred to instances in which the work of international artists-in-residence at VCUarts Qatar had been similarly curtailed (interviewee 2).

The establishment of VCUarts Qatar offers a poignant example of Qatar’s implicit public policy action on culture and, specifically, on artistic production. VCUarts Qatar both informs and restricts the types of artworks created by Qatar-based artists. Students learn artistic techniques and are encouraged, if not pressured, to engage in creative work within the limits of cultural sensitivities. Inevitably, this shapes the art produced, curated and viewed in Qatar. Arguably, the state of Qatar has some interest in artworks created locally, as indicated by QM’s claim to be ‘“local first” in its outlook, investing in the people of Qatar as a priority.’ In practice, QM’s museums and galleries and Doha’s public spaces have primarily exhibited international high-profile artists (Figure 2). Nonetheless, the work of some emerging Qatari and Qatar-based artists have been shown in Mathaf’s Project Space and at The Fire Station – a creative hub with private studio spaces and galleries.

The Fire Station hosts an annual residency open to Qatar-based artists, capped by an Art-in-Residence exhibition (Figure 3). The residency represents the main funding mechanism available to emergent local artists, and plays a significant role in shaping Qatar’s contemporary art production. This explicit cultural policy – that is, deliberate course of action seeking to shape the country’s cultural programme – operates in tandem with VCUarts Qatar. Many staff and alumni have been residents at the Fire Station, bringing both technical skills and lessons learnt about which subjects are haram or ‘prohibited’ in Qatar.

For example, having secured a residency, the graduate I mentioned above deliberately avoided religious topics, opting for artworks that, whilst loosely inspired by religious imagery, ‘worked with the society’ (interviewee 1). However, to ensure the work could be included in the final exhibition – the first opportunity the artist had to present their artworks in a flagship QM gallery (Figure 4) – this religious inspiration was unintelligible to the uninformed viewer.

As Mirgani emphasises, local artists, either Qatari or of other nationalities, have to carefully consider ‘intended, and even unintended, consequences of their production’ for their work to be supported, exhibited and acquired by state-funded organisations. As I have discussed, self-censorship regularly takes places in Qatar. However, implicit cultural policies effectively regulate and limit the artistic productions that Qatar’s creativity laboratories such as VCUarts Qatar and The Fire Station foster and permit. By subtly coercing local artists toward culturally acceptable artistic forms and narratives, the state of Qatar bypasses censorship altogether.

Importantly, decisions about what is created and exhibited are (in)directly shaped by cultural sensitivities and morality informed by Islamic values – what Tartousseih labels ‘implicit Islamic cultural policies’. These policies permeate several policy documents, including Qatar National Vision 2030, which describes the country’s strong Islamic values as the moral and ethical compass for its development and assigns public institutions responsibility to ‘preserve national heritage and enhance Arab and Islamic values and identity’.

Conclusion

If the radical works of some high-profile international artists have been championed by Qatar’s elite cultural policy-makers, stringent contractual obligations typically control the production and display of those works (interviewee 2). Occasionally, they have even been edited from Qatar’s cultural canvas through acts of what I call state self-censorship. The production of local artists is constrained in more subtle and implicit ways. Multiple actors in the local art ecosystem – expatriate museum professionals, academics working in local universities and, obviously, artists – are called upon to make countless decisions around what is appropriate and sensitive to Qatari culture. Arguably, these decisions have broader implications for the cultural sector, as they influence what gets created, exhibited and viewed in Qatar, including in the country’s main creativity laboratory: its only arts school.

Qatar’s museum sector is thus not only regulated through explicit cultural policies and the work of arts administrators but also through other strategic, more implicit courses of action, including education policies and Islamic cultural policies. Indeed, only local creative work regarded as inoffensive can be viewed in Qatar’s exhibiting spaces. Whilst this approach allows the state of Qatar to bypass conventional censorship mechanisms, it effectively delegates regulatory responsibilities to non-state actors, including art teachers, curators and artists, who are called upon to act as state censors and make decisions, sometimes arbitrarily, about what is appropriate. Clearly, implicit cultural policies strongly inform Qatar’s cultural programme. And they require close attention to appreciate how the complex nexuses of culture and policy in Qatar shape the country’s museum programme.

This is part of a series emerging from a workshop on ‘Heritage and National Identity Construction in the Gulf’ held at LSE on 5–6 December 2019. Read the introduction here, and see the other pieces below.

In this series:

- Introduction by Courtney Freer

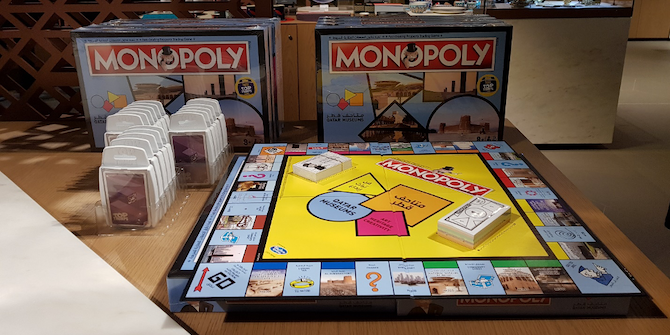

- Souvenir Sovereignty in Qatar by Suzi Mirgani

- Examining Kuwait National Museum by Sundus Alrashid

- Urban Planning and its Legacy in Kuwait by Alexandra Gomes

- Museums as Political Institutions of National Identity Reproduction: Are Gulf States an Exception? by İdil Akıncı

- The New Populist Nationalism in Saudi Arabia: Imagined Utopia by Royal Decree by Madawi Al-Rasheed

- Heritage and Sectarianism in Bahrain by Thomas Fibiger

- Dubai Expo 2020 and Ancient Mercantile Heritage by Robert Mogielnicki

- Managing UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Saudi Arabia: Contribution and Future Directions by Abdulelah Al-Tokhais

- Finding Mariam: The Invisible Woman in Kuwait’s National Heritage Mythology by Alanoud Al-Sharekh

- Cultural Attendance: Attracting the Crowds to Museums in Saudi Arabia by Maha al-Senan

- Religion and Heritage in the Gulf: Significant in its Absence? by Courtney Freer

- Historical Archaeology in the Gulf by Robert Carter

- Militarised Nationalism in the Gulf Monarchies: Crafting the Heritage of Tomorrow by Eleonora Ardemagni

- The Practice of Heritage in the Northern United Arab Emirates by Matthew MacLean

- Displaying the Nation in Museum Exhibitions in Qatar by Alexandra Bounia

- The UAE State ‘Rebirthing’ of Motherhood: Who is birthing who? by Rima Sabban