by Benjamin P. Nickels

Political scientists sometimes distinguish between performance legitimacy and personal legitimacy. Certain regimes remain in power thanks to what they provide: things like security and order, economic growth, clean streets. Think Singapore or Rwanda. In other countries, a shared culture and history determines who has the right to rule, whether or not that ruler performs well. The king of Morocco enjoys this type of authority. Personal legitimacy has been the coin of the realm in Algeria, and fighting the French has been a prerequisite for top positions. Until now, every Algerian head of state has been an ancien moudjahid, a former militant in the War of Independence, or what Algerians call the Revolution.

That source of legitimacy is coming to an end. The war started in 1954 and finished more than 56 years ago, with a ceasefire on 18 March 1962. As the years go by, the president’s age has gone up. Ahmed Ben Bella and Houari Boumediene held office in their thirties and forties, Chadli Benjedid and Liamine Zeroual in their fifties and sixties. Abdelaziz Bouteflika became president at 62 and was forced from office last month at age 82, his own physical decline the symbol of a fading generation. Over the decades, respect for these elderly militants-turned-politicians has soured among Algeria’s ever-younger population. But on what other basis can the next president claim leadership?

The answer is not forthcoming from the regime, which so far seems unimaginative. A 77-year-old Bouteflika loyalist is now interim head of state, leaving vacant the presidency of the Council of the Nation. That post has been backfilled by a decrepit 88-year-old ancien moudjahid, Salah Goudjil, who has been ridiculed in a video making the rounds on social media that shows him unable to read a speech to the nation’s senators. Meanwhile, Army Chief of Staff Ahmed Gaid Salah, a 79-year-old former militant derided by protesters, continues to prepare the 4 July elections. Perhaps a vigorous young candidate will be selected and backed by Algeria’s powers-that-be, le pouvoir, through some obscure decision-making process that resists analysis. ‘The word most often used to describe Algerian politics is opaque,’ I once heard a seasoned US diplomat wryly observe after years in Algiers. But a government-endorsed nominee of any age will have to explain his or her connection to the maligned system.

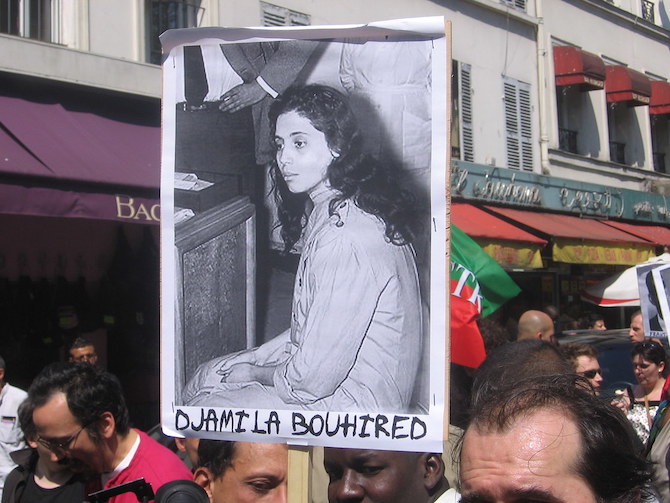

More worryingly, no novel concept of legitimacy seems to be emerging from the streets. Algerians may be too young to remember the violence of the 1990s, much less the 1960s, yet their protests are replete with references to the War of Independence. Browse the online presence of Mouwatana, a citizen group organising opposition rallies, and you will see statements reclaiming rights promised in 1954 and calls for protest set on black-and-white backdrops of demonstrations during the Revolution. Look back at the Facebook page of the Barakat Movement, whose members helped found Mouwatana and who had already contested Bouteflika’s candidacy in the 2014 elections, and you will find praise for heroic Revolutionary martyrs and anger that Algeria’s valiant people have been led astray. Read the words of the 83-year-old Djamila Bouhired, a venerated hero from the Battle of Algiers who joined the street protests this past March. She accuses Algeria’s rulers of serving France and denounces them as cowardly imposters who never truly sacrificed for Algeria’s freedom, using a string of epithets – 19 March (i.e., the day after the ceasefire) ‘freedom fighters’, maquisard latecomers, the Army of the Frontiers, and so on – that take their meaning and force entirely from the War of Independence.

Alternatives for authority are scarce. Performance legitimacy is doubtful: no leader can fix Algeria’s economic and social problems in the near term, especially given the substantial drop in oil prices and in Algeria’s foreign reserves during the last five years. Of course the Islamists claim a religious right to rule, and last month thousands did turn out to bury Abassi Madani, a founder of the Islamic Salvation Front. But the disaster of the 1990s shattered the Islamists’ standing among ordinary Algerians and made them unacceptable to le pouvoir. Divisive identity politics might mobilise broad constituencies, playing on tensions between Arabs and Berbers or exploiting regional grievances in Kabylie or the South. Perhaps a creative politician might renew a national sense of purpose by revamping the global standing Algeria once held in the glory days of nonalignment and Third Worldism.

More likely, given Algeria’s economic woes and the widespread anger against the system, a skilled populist could mount a formidable outsider campaign by claiming to represent the people against a crooked elite. The spate of corruption scandals, arrests, and falls from grace of key officials that began last summer may in fact reflect the regime’s attempt to get out in front of growing public disaffection – not just elite jockeying for position or an obscure settling of scores. In any event, not even populism is likely to last in Algeria, and sooner or later the country must face its political inheritance and find a new basis of authority for its political class. Without some way to legitimatise rule, the temptation to simply repress the demonstrators and disqualify debate will remain strong. ‘Turning the page’ and silencing dissent has also become something of an Algerian tradition.

Algeria’s past is a mixed blessing for its politics. The revolutionary legacy gives Algerians a fierce sense of national pride, a savvy and often trenchant sense of humour about public life, and a political discourse that reveres the popular will. It also produced a security state that settles matters through secrecy and violence, eliminates prominent innovators, and frames disagreements in terms of betrayal, conspiracy, and foreign manipulation. Algerians are understandably attached to their history, but the past alone cannot chart the country’s future. Algeria’s next leader, whoever it is, should work to transform the Revolution’s legacy into a modern political vocabulary that can mobilise Algerians to solve today’s problems. Politicians will need that language, and the country will need that new basis for legitimacy, if Algeria’s government and institutions are to truly take root and thrive in the years ahead.

Ben Nickels is professor of international security studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Germany, where he is course director of the Europe-Africa Security Seminar. Views expressed here are his own. He tweets at @BPNickels

Ben Nickels is professor of international security studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Germany, where he is course director of the Europe-Africa Security Seminar. Views expressed here are his own. He tweets at @BPNickels

I read recently.

People in Algeria speak the Arabic language. According to data on inbound tourists in Algeria, 2,634,000 tourists arrive in the country each year. How can such a number of tourists visit a country with such a situation?