by Sean Foley

On 8 May 2019, Prince Badr bin Farhan, Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Culture, presided over the opening of his country’s pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, one of the world’s premier art exhibitions. The pavilion, which highlighted Saudi Arabia’s art and culture, came as a surprise to many Middle East experts. In their view, most Saudis are an intolerant, dogmatic people who have sought to preserve both their society’s culture and Hanbali Islamic traditions against modern art and any other manifestation of the contemporary world—a view reinforced by some Saudis. For instance, writing in a daily newspaper in 2013, Saudi sociologist Abdulsalam al-Wayel declared: ‘If we can say that there is a “Saudi culture,” and it has value, then we can also say with high confidence that the contempt for the arts lies at the heart of its values.’

By contrast, my new book—Changing Saudi Arabia: Art, Culture, and Society in the Kingdom—seeks to broaden our discussion of Saudi artists and their country, which is often defined by many non-Saudis entirely through the words of its national leaders. While such official pronouncements are essential to understanding Saudi diplomacy, they are not as useful for analysing other elements of the kingdom. In these contexts, artists are essential, for they permit us to transcend the dialectical structures that exist in most Western discussion of Saudi Arabia, frameworks that Edward Said warned us to avoid in Orientalism, his seminal text on how Western scholars have understood the peoples of Asia, North Africa and the Middle East.

As I have learned during extensive in-country and online research for my book, the Saudi creative class is in touch with a powerful national force: the deep consciousness of the masses now living in the country and dealing on a day-to-day basis with new societal issues, both as results of its diversity and its many opposing elements. What is their country? What ‘Saudi Arabia’ emerges from their perceptions? These questions pose a powerful challenge to Western scholars, who have for too long overlooked the kingdom’s culture and society—compelling us to change not only how we look at Saudi Arabia but also how we look at ourselves.

One of the important lessons that I have learned in my research on Saudi artists has to do with the nature of social change and modernity. For many years, one heard the same complaint over and over again about the kingdom: ‘Saudi Arabia must change.’ This sentiment missed the fact that Saudi Arabia has changed over the past century and remains a nation in motion—even as it outwardly retains its traditional governmental and social structures. This process may not be sufficiently dramatic to be taken seriously by some analysts, nor is it likely to resolve the tensions between modernity, tradition and other oppositional forces that exist in the kingdom. But it is a tangible force, which shows what the kingdom’s art teaches us about modernity in the contemporary world. Saudi Arabia and other non-Western cultures like it may bend and yield to modernity, but they can also shape it and sustain contradictory forces without necessary plunging into the abyss between the medieval and the modern worlds.

To see how this process has unfolded in the kingdom, one should look at three students who graduated in the early 1990s from a high school in Khamis Mushait—a city of half a million people in Asir Province, 200 kilometres (124 miles) from the Saudi-Yemeni border in the kingdom’s southwest.

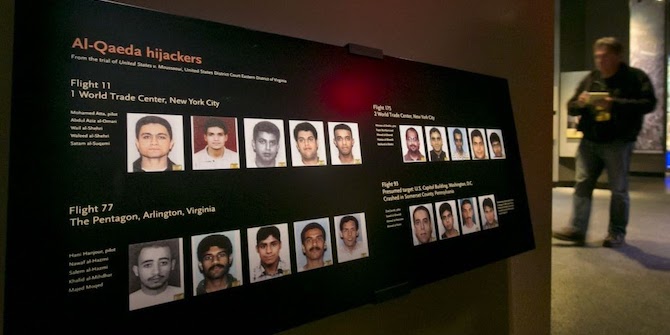

Two of the students, Wail al-Shehri and Waleed al-Shehri, his younger brother, participated in the attacks of 11 September 2001, an operation that used modern technology in the service of a cause that the perpetrators defined as both ‘religious’ and expressive of a ‘tradition’—jihad. Religion and tradition were precisely the forces that modernism and its technology were predicted to replace.

By contrast, the third student, Abdulnasser Gharem, became an officer in the Saudi army and serves to this day as a driving force behind the contemporary Saudi arts movement, which eschewed many modern artistic and cultural norms based on the Western notion of the artist as an ‘individual.’ Instead, the art movement, which Gharem helped to pioneer in the early 2000s in Asir, reimagined these norms to fit those of the kingdom, a decision that laid the groundwork for the economic, social and government reforms that have occurred in recent years. Nonetheless, Gharem and his infamous classmates, as the Saudi artist has himself admitted, are nearly identical. ‘We have the same knowledge,’ Gharem says, ‘the same environment… We are almost the same.’ That ‘almost,’ with its powerful, provocative irony, is important.

Ultimately, Gharem’s ability to admit his links to the al-Shehri brothers says much about him personally as an artist but also provides insight into why the Saudi people have weathered the crisis in the Middle East over the last decade. They have, in general, avoided the existential questions that have paralysed many other states in the Middle East and forced many Arabs to choose between incompatible conceptions of national identity and how to view the world. Gharem’s ‘almost’ is an assertion that other possibilities exist. Both he and the al-Shehri brothers came from the same soil, but where the brothers went in one direction; he went in another. The implication is that it is necessary first to recognise the various potentialities existing in a situation and then to choose the best option. Gharem was not the angel as opposed to the bad boys—they were boys like any other. They tragedy is that the al-Shehris were not able to find a better solution. Indeed, Gharem is keenly aware that Saudis are used to negotiating among wildly disparate contexts—contexts which many in the West and some in the Middle East may find ‘contradictory’, but which Saudis themselves experience as part of the multiple faces of reality.

Sean Foley’s book, Changing Saudi Arabia: Art, Culture, and Society in the Kingdom, was reviewed by the Centre’s Courtney Freer for the blog here.

Sean Foley is an Associate Professor of History at Middle Tennessee State University, who has published widely on Middle East and Islamic history and Gulf politics. He is the author of Changing Saudi Arabia: Art, Culture, and Society in the Kingdom (2019) and The Arab Gulf States: Beyond Oil and Islam (2010)—both of which were published by Lynne Rienner Press. For more on his work, see his website: www.seanfoley.org. He tweets at @foleyse