by Rana AlMutawa

Frustrated with people’s ideas about ‘authentic’ Mexican culture, John Paul Brammer in a piece for the Washington Post denounced seekers of authenticity for expecting his culture to conform to a restrictive imaginary of ‘Mexican-ness’. In one example, he described how people expected to see emblems of poverty and struggle in Mexican restaurants as a feature of these places’ ‘authenticity’:

What makes something “authentic”? …[M]ost of the hallmarks seem to be about pain: dirty floors, plastic chairs, anything that aesthetically connotes struggle. The cooks and waiters ought to have accents. There should probably be a framed photo of someone’s dead grandpa…If the joint has no air conditioning, if it’s off the beaten path, if the voyeur into struggle has to “work” to find it, then the experience is supposedly richer for it. It makes the voyeur better, more worldly for having brushed up against it.

Brammer argues that the quest for authenticity is a shallow pursuit of the rarefied and exotic – the ‘grittier’ the experience, the better the seeker feels about their quest and their identity as a socially aware individual. Perhaps this appears as a harsh judgment on those seeking authenticity. Some may genuinely be interested in being exposed to new and different experiences, people and cultures. Yet ‘authenticity’ not only exoticises and restricts cultures, as Brammer notes, but also serves as a way for its seekers to present themselves as morally or socially superior to mainstream society.

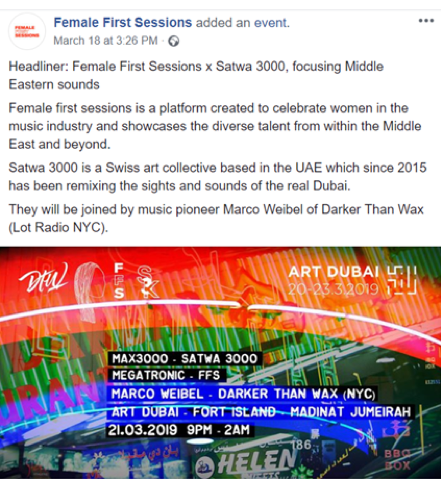

A similar pattern has appeared in my research on Dubai and among many individuals who seek authenticity in the city. Although not uniformly, these individuals were often of the creative class, including artists, academics or creatives who differentiated themselves from mainstream society. While they did not explicitly reference poverty or struggle as a prerequisite for authenticity, many used lower-income neighbourhoods as examples where ‘real life’ happened. Some referred to places like Souq Naif or the creek area (generally older, working-class neighbourhoods in the city) as authentic places where they could finally find ‘real people.’ In the post below, for example, is an ad by a Swiss art collective in Dubai who named themselves Satwa3000. Their ad describes them as a group ‘remixing the sights and sounds of the real Dubai’ (emphasis added).

By singling out the city’s ‘authentic’ spaces and rejecting the ‘glitzy’ ones, some individuals were shunning elements of society that they genuinely viewed as harmful, unsustainable or ‘superficial.’ They felt they were rejecting a society of the spectacle or a culture that valued appearances, and instead opting to be in environments where they could have meaningful connections with people. These individuals did not want to be in spaces where they felt monitored, watched or restricted in their behaviour, but in places which allowed them to foster a sense of ownership over a place and a sense of community. Meanwhile, another of my interlocutors said that she went to the lower-income spaces of the city to ‘unlearn’ the racist and classist things she had heard about the inhabitants and to challenge her own perceptions of these places.

Some reasons given for choosing to socialise in certain places (or for shunning them) may well be noble. But alongside these genuine intentions were sometimes, perhaps oftentimes, reasons based on performances of distinction. Contrasting themselves to other people who flocked to the newer parts of the city because they were attracted to its glamour, many of the individuals in the creative class saw themselves as different from mainstream society; as more socially aware. Some of them directly or indirectly criticised a ‘herd mentality’, the eschewal of which they believed differentiated them from others. They viewed their rejection of malls or the new, commercial developments as a moral stance in opposition to consumption or an ‘idle life.’ These were often expressions of their cultural capital and supposed moral or intellectual superiority.

The quest for ‘authenticity’ as a means to fashion one’s own image has been documented in different parts of the world. Terressa Benz wrote about individuals working in the creative fields, such as in arts and technology, who moved into poorer neighbourhoods of downtown Los Angeles and equated poverty and ‘danger’ with authenticity. Being in contact with low-income residents or homeless people was a way for them to accumulate cultural capital as represent themselves as more ‘authentic,’ ‘cool,’ or socially aware individuals.

Another example of a ‘stereotypical authenticity’ can be found in the way people associate ‘authentic’ blues music with their own caricatured ideas of black and working-class people and neighbourhoods. Grazian described these stereotypical expectations:

Authentic blues clubs are ramshackle joints with broken front doors and rattling sound systems; they are dimly lit, unbearably smoky, and smell as funky as their music sounds…and are located in slightly dangerous black urban neighbourhoods, or else off the deserted highway, deep in the sticks. They only hire authentic looking blues musicians, who are generally uneducated American black men afflicted by blindness, or else they walk on a wooden leg or with a second handcrutch; as they are defiantly poor …Their audiences are usually black as well, with the occasional white customer surfacing only if they are also sufficiently old, poor, drunk, or blind.

Grazian noted that these individuals’ quest for authenticity afforded them ‘bragging rights, which accompany any consumed experience of authenticity,’ resulting in these individuals being viewed as hip and cosmopolitan – status symbols for them. Similarly, in Dubai, some of the creative classes (similar to the ones Benz described) seek and consume authenticity as a means to establish their identity as distinct from the ‘masses.’ Although they criticise those they condescendingly refer to as ‘the masses’ – who congregate in the ‘glitzy’ sides of the city –for displaying their social status (and distinction) through the spaces they inhabit and their consumption patterns, the creative class also have their own performative practices that they use to flaunt their own cultural capital, and their authenticity.

We should be able to critically reflect on our cities’ urban landscapes without resorting to labels of authenticity and superficiality. There is much to discuss about Dubai’s new developments, such as to what extent they are accessible to users of different social classes, and who is being included and excluded in these newly built cities. Several people, for example, have noted concerns about the new Al-Seef development on the creek which boasts relatively expensive restaurants, ones which many inhabitants of that area are not able to afford. As it is in different parts of the world, working-class neighbourhoods are often stigmatised or perhaps deemed ‘irrelevant,’ and bringing (positive) attention to them and acknowledging their significance to the city (if done in the right way) is important.

However, by labelling other spaces (such as malls or new developments) as ‘fake,’ performers of authenticity inadvertently dismiss the social meanings being created within these places as well. So-called superficial places can be important venues of everyday life, ones which are re-appropriated and re-used in different ways, ranging from being meeting spaces for members of a community or spaces where women can engage in flânerie, which they could not do elsewhere. They are spaces that house people’s memories of their childhoods or teenage years, ranging from mundane recollections of family dinners to more exciting ones such as a first outing without adult supervision. These meanings are dismissed by those seeking authenticity.

The stereotypical ideas of authenticity results in people dismissing their everyday lived experiences as inauthentic based on confined and narrow expectations of it. Most people I spoke to in Dubai cited spaces and practices they rarely ever use themselves, such as buying spices from the old souq, as examples of ‘authentic culture.’ Brammer’s frustrations with seekers of authenticity apply here again: they seem ‘more invested in the feeling of realness than in any kind of truth.’

This piece is an edited version of a longer article published in Urban Anthropology, available here.

The Instrument provides a melodic and rhythmic feature making the India raga more expressive and popular. Its main attraction is the ‘Nadham’ or the ‘tone’ which creates a positive energy.

If you want to read more on this, click the link below

https://antaraedu.com/courses/musical-swara-instruments

Dear Rana I like your attempt to sort out the concept of authenticity as applied to the creek deira or bur Dubaï in contrast with new urban developmens. You are mixing new uses or gentrification like bastakiya with a qualification.of snob society trying to distinguish itself from the ignorant and uneducated mass of tourists or expats. There is a similar bias in your approach condemning these self designed “elite” ; but this is enhanced by the municipality s policy to create fake héritage while marginalizing dubai s original identity and culture as anywhere in the world. There is both a political and a material view in attracting fashionable activities in a reshaped heritage to hide the true human and cultural fabric of the city. But let me free to feel better in these areas than in.jumeira, walking at night to my favorite iranian shops or pakistani restaurants and have nostalgia of the time where the last landmark was the world trade center. Old dubai is another city but a true and lively city too, with its own attractiveness to others than those searching for superficial distinction. But conhratulations for your interest in tackling this subject which might deserve more elaboration.