by Rufat Ahmedzade

The Eastern Mediterranean Offshore Gas Dispute

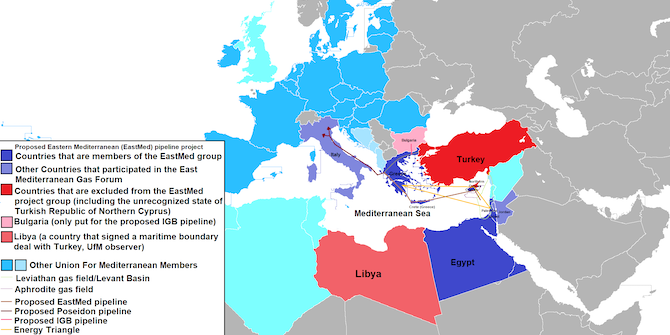

Libya has become the focus of Turkish President Erdoğan’s assertive foreign policy in the wider region ever since tensions increased over the Eastern Mediterranean’s offshore gas resources. Excluded from cooperation on the development and export of gas to European markets, Turkey decided to back up its claim through a belligerent stance, sending warships into Greek waters, organising military exercises and carrying out its own drilling for hydrocarbons.

Earlier this year, the leaders of Israel, Greece and Cyprus signed an accord on construction of a pipeline to export gas from newly discovered offshore deposits in the southeastern Mediterranean to Europe. Erdoğan interpreted this as a clear attempt to sideline Turkey from regional strategic matters. Turkey worries that the deal bypasses it – for the first time – in energy transportation to Europe, as Ankara has traditionally played a special role in transporting Russian, Iraqi and Azerbaijani oil and gas to Western markets.

Turkey’s relationships within the region are already fraught due to President Erdoğan’s aggressive foreign policy ambitions. Ankara has complicated the future of the EastMed project by signing a controversial maritime delineation deal with the UN-recognised Libyan government. Turkey’s move is an attempt to counter the EastMed project and to re-establish itself as a vital player in the region. Not surprisingly, immediately after the signing of the maritime deal with the Tripoli-based Libyan government, the Turkish president said that no energy project in the region could be completed without his country’s participation. President Erdoğan defended the maritime memorandum with Libya by saying that Turkey cannot be imprisoned in its own waters and has to have a major role in regional energy projects.

In addition, involving Turkey in Libya’s multisided civil war on the side of the Tripoli-based government, Erdoğan appealed to nationalistic and religious sentiment. He referred to Libya’s historical bond with Turkey as a former Ottoman province, and cited Ataturk’s role in Libya as an Ottoman military commander in the fight against the Italians in 1911–12. President Erdoğan’s neo-Ottoman assertiveness poses a major risk to Turkey’s ability to project military power, as the country is involved in regional conflicts on three fronts. Russian airstrikes on Turkish military units in Syria have shown how vulnerable an overstretched Turkey really is.

Turkey’s Libya Gambit and Risks

As Turkey faces a backlash from Greece, Cyprus, Israel and the European Union over its deal with Libya, the country’s support for the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA) is also setting Turkey against French geopolitical interests. The French embassy in Greece issued a statement at the end of March, declaring the maritime deal between Libya and Turkey ‘invalid’. Under the security cooperation agreement with the GNA, Ankara has already deployed a small number of Turkish forces alongside the Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army group as military ‘instructors’ to aid the internationally recognised government in Tripoli against the controversial warlord Khalifa Haftar. Haftar’s backers include France, the UAE, Egypt and Russia, though he has been accused of war crimes in Libya by international human rights agencies. Last year, after strong military and political support from the UAE, Egypt, France and other countries, Haftar launched a military offensive against the GNA government. Turkey defends its involvement in the conflict as ‘legitimate’, as its presence came at the request of Libya’s UN-recognised government.

France’s backing of Haftar – an attempt to install a strongman in Libya – seeks to achieve the same strategic objectives it had after the overthrow of Colonel Qaddafi in the French-led NATO intervention in 2011. Paris has a special economic interest in Libya’s oil and gas industry, as Wikileaks revealed through a leaked email from Sidney Blumenthal to then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in 2011. Paris has also been seeking to increase its political influence in North Africa and combat Islamist groups in the Sahel region. Since the downfall of Qaddafi, Libya has become an entry point for illegal migration to Europe, which French President Macron wishes to curb. France sees Turkey endangering French interests by supporting the government against Haftar. Thus, the collision of French-Turkish interests risks more chaos in war-torn Libya for years to come. If Turkey and Russia reach a deal and pressure both sides to agree a ceasefire, French interests would be in jeopardy as Turkish-Russian cooperation might sideline Paris.

The UAE and its Arab allies, primarily Egypt, are also playing a disruptive role in the civil war. It is no secret that Haftar’s military gains were achieved thanks to UAE air support including drones and piloted aircraft. Since 2015 Haftar has been receiving ample military and political support from his backers, which has helped him to control vast swathes of the country from his headquarters outside Benghazi. Supplying weaponry to Haftar, despite international arms controls, fuels the criminal militias under him and disincentivises them from seeking a political solution. The UAE’s support for Haftar is part of their wider strategy to prevent and abort any democratisation in the Middle East and North Africa, and reinstall friendly dictators. Though French President Macron strongly objects to the Turkish involvement in Libya, Ankara’s involvement is considerably smaller than Abu Dhabi’s, which France makes no mention of. Victory for Haftar would create a pro-Paris Libya – a centrepiece of French foreign policy aspirations since 2011.

Turkey and Russia did try to broker a ceasefire between the warring sides in Moscow in January 2020. However, Haftar declined to sign the deal after consulting with his backers. The disastrous French involvement in Libya has already created a foothold for Russia, as Moscow’s mercenary Wagner Group has a strong military presence inside the country. If Turkey and Russia can work together as they have done in Syria, France and its Arab allies look set to be sidelined. However, Ankara’s Libya adventure is going to be costly and the future of Turkey’s opposition to the EastMed project increasingly depends on the outcome of the Libyan Civil War.

4 Comments