by Ian Black

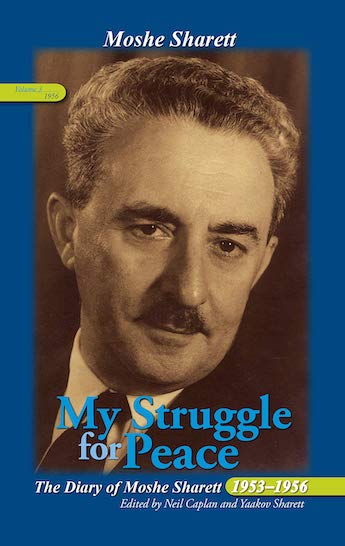

Moshe Sharett was Israel’s first foreign minister, from 1948 to 1956, and served briefly as its second prime minister from 1954–5. He was a leading figure in Mapai (the forerunner of the Labour Party) from the early 1930s. His Personal Diary was published in Hebrew in 1978 in eight volumes, attracting rave reviews and wide interest for such a highly detailed work. Over 40 years later it has been translated into English and expanded to include declassified archival material, released as My Struggle for Peace: The Diary of Moshe Sharett, 1953–1956 (Indiana University Press, 2019) and edited by Neil Caplan and Yaakov Sharett.

Moshe Sharett was Israel’s first foreign minister, from 1948 to 1956, and served briefly as its second prime minister from 1954–5. He was a leading figure in Mapai (the forerunner of the Labour Party) from the early 1930s. His Personal Diary was published in Hebrew in 1978 in eight volumes, attracting rave reviews and wide interest for such a highly detailed work. Over 40 years later it has been translated into English and expanded to include declassified archival material, released as My Struggle for Peace: The Diary of Moshe Sharett, 1953–1956 (Indiana University Press, 2019) and edited by Neil Caplan and Yaakov Sharett.

This three-volume edition sheds light on key political, diplomatic and domestic developments in the state’s formative period in the early 1950s. In 1955, for example, when former Israeli paratroopers crossed the ‘green-line’ border into Jordan and executed three Bedouin (in revenge for the murder of the one of the ex-soldier’s sisters) the army and political elite closed ranks to block enquiries and defend the perpetrators. Sharett was devastated and lamented the fact that an act of vengeance ‘had been elevated to the level of a moral principle.’

Significant parts of what he recorded privately deal with his often-tense relations with David Ben-Gurion, the country’s first prime minister and the overwhelmingly dominant leader of his time, (who he eventually replaced for 21 months.) The diary is well-written, unusually candid and has now been meticulously translated, edited and annotated by Sharett’s son Yaakov and Neil Caplan, the author of several definitive academic studies of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Earlier, in October 1953, Sharett (then foreign minister) had to deal with the international fallout when an Israeli army unit – commanded by a rising star called Ariel Sharon – attacked the West Bank village of Qibya and killed at least 69 Palestinians, many of them women and children. The raid was in retaliation for a Palestinian fedayeen grenade attack that killed an Israeli woman and her two children. Ben-Gurion initially claimed that it had been carried out by enraged civilians. Sharett opposed it in advance and was horrified by the ‘unending stream of very bitter reactions,’ including by Jews living abroad.

Detailed entries cover Israel’s foreign relations – with the US, Britain, Russia and the UN – as well as immediate neighbours Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon and Syria. Sharett routinely met ministers, dignitaries and celebrities. He was an accomplished (if pedantic) linguist, speaking native Russian (his father was from southern Ukraine) as well as Hebrew, English, Turkish, German and, highly unusually, fluent Arabic, because as a child in Ottoman times his family had lived in a West Bank village between Ramallah and Nablus, far from any area of Jewish settlement. He enrolled at Istanbul University and volunteered for the Ottoman army in the first world war, studied at LSE in the 1920s and worked for the Mapai newspaper Davar before joining the Jewish Agency Executive’s political department. His own journalistic experience made him extremely conscious of the media.

Border incidents, Arab infiltration, and the run-up to the Suez crisis were Sharett’s main preoccupations in both his roles in the 1950s. But his commitment to ‘sober statesmanship’ proved incapable of challenging Ben-Gurion and the Israeli army’s charismatic chief of staff Moshe Dayan. Sharett lost the ‘historic and fateful confrontation…with opponents who sought to resolve the conflict through military prowess,’ writes the historian Yechiam Weitz in his introduction.

That long-anticipated ‘second round’ of the conflict, in collusion with Britain and France, came about despite Sharett’s enduring preference for diplomacy over the use of force, and led to the humiliating end of his own political career. Two years earlier, however, he had successfully opposed plans by Defence Minister Pinchas Lavon to attack Syrian artillery positions as well as a call by Ben-Gurion to intervene to arouse Lebanon’s Maronite community to unilaterally declare a Christian state. Lavon’s involvement in an Israeli intelligence-gathering network in Egypt (aka ‘the mishap’), which involved the execution of two Egyptian Jews, was another low point.

Sharett’s views stand in striking contrast to the policies of Israeli governments of recent years – but he was of course in office long before the watershed moment of the 1967 war and the revival of the still unresolved Palestinian question; and before the lurch to the right with the victory of then-Likud leader Menachem Begin a decade later. (Sharett died in 1965.) Weitz argues that Sharett was influenced both by his childhood experience of living amongst Arabs and by being in the first class to graduate from the Herzliya Gymnasium in Tel Aviv (the first Hebrew high-school in the Ottoman era) and as a result was less ideologically driven than many of his East European-born socialist Zionist contemporaries. In 1954, for example, he complained that the ‘almighty word’ – security – was too often invoked as a reason for vetoing positive plans to improve the situation of the country’s Arab minority.

‘What we can and should be aware of,’ as Yaakov Sharett wrote of his father five years ago, when Likud’s Binyamin Netanyahu was at the peak of his power, ‘is that once there was in Israel one prime minister who advocated and believed in restraint, compromise and moderation, and that his road was not taken.’