by Mohammad Ataie, Raphaël Lefèvre, Toby Matthiesen

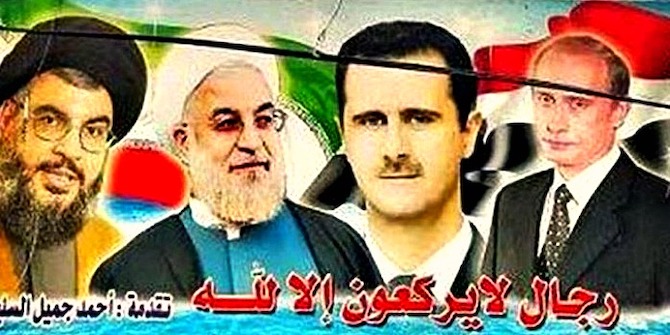

Although forty years have now passed since the downfall of the Shah, Iran’s 1979 Revolution continues to be the subject of much scholarly discussion. The global impact of the Islamic Revolution has generated much academic and policy attention, especially with respect to how it spurred the growth of militant Shi‘a Islamist groups, such as Lebanon’s Hezbollah. Yet this focus on the relationship between the Islamic Republic and Shi‘a across the world obscures not only the complex dynamics which typify transnational Shi‘a politics, but also the impact which the revolution had on many Sunnis in the Middle East. Indeed, even as this may appear surprising in a contemporary context marked by Sunni-Shi‘a sectarian tensions, the Iranian Revolution inspired, and sometimes even empowered, Sunni Islamist clerics and groups who viewed it as an Islamic – rather than narrowly Shi‘a – achievement.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s Mixed Reaction

Although some of its branches would later grow critical of Tehran, the Muslim Brotherhood was key amongst the Sunni Islamist groups which initially applauded the Iranian Revolution. This was partially because of the coming to power of clerics who expressed a willingness to implement Islamic law, thus coming close to the Muslim Brotherhood’s own idea of what an Islamic state should look like. But it was also because some of the leading Iranian revolutionaries drew intellectual inspiration and references from Brotherhood ideologues such as Hassan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb, whose books they translated into Persian and made Iranian activists read. As a result, the Islamic Republic invited Muslim Brotherhood delegations to come to visit Tehran. The early stage of the Revolution was a time marked by strong ideological and social bonds between Shi‘a and Sunni Islamism.

Yet, by the early to mid 1980s, the Muslim Brotherhood started to distance itself from the Islamic Republic of Iran. Several factors explained this newfound caution. One of them was Iran’s own domestic politics and the sense that the clerical faction associated with Ayatollah Montazeri, which was inclined to forge alliances with Sunni Islamists, was being marginalised in Iran. Another factor was that the Islamic Republic’s ideology began revolving less around pan-Islamist ideas and more distinctly around Ayatollah Khomeini’s concept of wilayat al-faqih (or ‘rule of the jurisprudent’), which hailed from a specifically Shi‘a tradition and was less compatible with Sunnism. Finally, while Iran soon emerged as the vanguard of a new, revolutionary breed of Islamism, it began to politically, financially and logistically sponsor Shi‘a as well as Sunni Islamist groups that were more militant than the Muslim Brotherhood, and thus challenged the group.

Inspiring a Generation of Militant Sunni Islamists

Long before turning into a key supporter of Hamas in the 2000s, the Islamic Republic had indeed sponsored an array of militant Sunni Islamist groups. A prominent example is the Palestinian group Islamic Jihad. In the West Bank and Gaza as well as in Lebanon’s Palestinian camps, the Iranian Revolution was widely praised, for one of the first moves of the Islamic Republic had been to hand over the Israeli embassy in Tehran to the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO). It was as the much hoped-for Khomeini-Arafat axis soon came to an end, partly as a result of the PLO’s pro-Iraqi stance in the Iraq-Iran war, that the Islamic Republic supported the creation of the militant Sunni Islamist group Islamic Jihad. The Islamic Republic of Iran also inspired the growth of other, less well-known militant Sunni Islamist groups in the Middle East. For instance, in the Lebanese city of Tripoli, the revolutionary Sunni cleric Sa‘id Sha‘aban emerged as an advocate of what he called the ‘Iranian model’, for Islam’s victory over the West. In the wake of the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, he formed the Islamic Unification Movement (better known as ‘Tawhid’), a Sunni Islamist armed group which fought leftists and Syrian army troops and turned Tripoli into a small, proto-Islamic state for three years. Tehran entertained close relations with these Sunni Islamists in Tripoli, who in turn promoted the Islamic Republic’s revolutionary ideology and interests in Lebanon and forged strong bonds with Iran’s other Lebanese Islamist ally, Hezbollah.

A Pan-Islamic Sunni-Shi‘a Front?

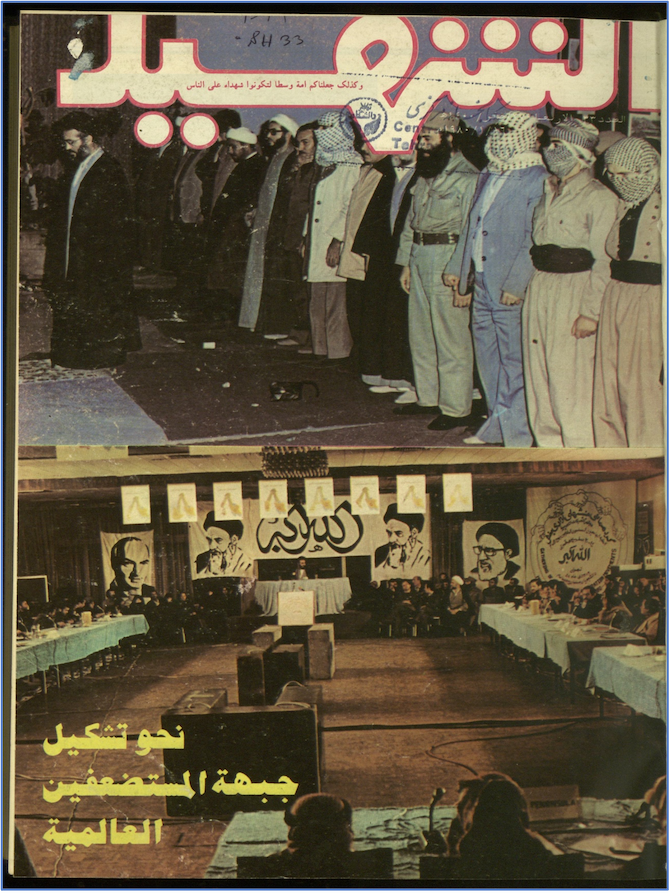

Central to Iran’s efforts to reach out to militant Sunni Islamist groups were the ecumenical platforms set up to reinforce ties with Sunni clerics, to pave the way for a global alliance of Shi‘a and Sunni Islamist militants. In January 1980, soon after the Revolution, the newly established Islamic Republic invited dozens of third-worldist revolutionaries to Tehran, with the implicit goal of uniting Sunni and Shi‘a militants. In subsequent years it organised Global Assembly of Muslim Scholars and Unification Week conferences to sustain the ecumenical network of Sunni and Shi‘a militant clerics who supported Iran’s foreign policy. In Lebanon, this Sunni-Shi‘a network of pro-Iran clerics even founded a clerical organisation, the Association of Muslim Scholars, which fought against Israel.

The revival of narratives of Arab-Persian rivalry triggered by the Iraq-Iran war of the 1980s as well as sectarian tensions in the wake of the Syrian opposition’s defeat at the hands of the Assad regime in 1982, undermined such efforts.

But the legacy of the Iranian Revolution’s impact on Sunni Islamists is understudied. Shedding light on how the proponents of Sunni and of Shi‘a Islamism once influenced and inspired each other, and forged alliances, contributes to our understanding not only of the Iranian Revolution’s global impact, but also the making of modern Islamism.

This blog post introduces the project, ‘Whose Revolution? Re-assessing the Impact of the 1979 Iranian Revolution on Sunni Islamism‘, which is funded by an award from the Henry Luce Foundation.

2 Comments