by Samuel Ramani

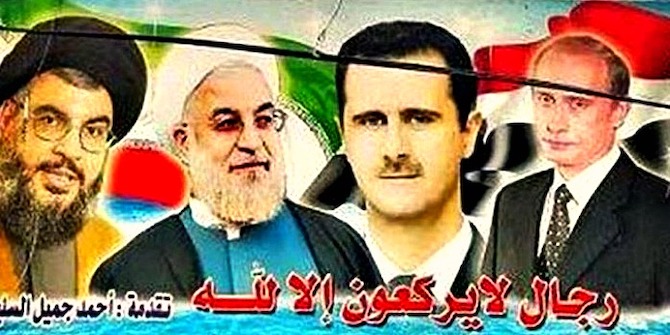

A decade after the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, Russia and Iran continue to dominate Syria’s geopolitical landscape. Russia’s influence is undergirded by its naval base in Tartous and air base in Hmeimim, as well as its ability to carry out decisive airstrikes on Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s behalf. Iran’s leverage hinges on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) extensive military presence in eastern and southern Syria, which is complemented by Hezbollah and a vast network of Assad-aligned Shiite proxies. While Russia and Iran remain military and diplomatic partners in Syria, it is unclear whether this alignment will persist into the presumed post-conflict reconstruction phase or if it will extend to other Middle Eastern conflicts, such as Yemen.

The Evolution of Russian-Iranian Cooperation in Syria

When mass protests in Dera’a intensified into a nation-wide civil war in the spring of 2011, the prospects for strategic cooperation between Russia and Iran in Syria appeared slim. In June 2010, Russia voted for UNSC Resolution 1929, which imposed multilateral sanctions on Iran. President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was concurrently pursuing legal action against Russia for a breach of its S-300 delivery contract with Iran. Russia’s cautious counter-revolutionary position in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Bahrain clashed with Iran’s support for the Arab Spring uprisings against pro-American regimes in the Middle East and its long-standing nemesis Muammar al-Gaddafi.

Due to this overhang of discord between Russia and Iran, the alignment between both countries in Syria was largely instrumental during the first two years of the civil war. Iran viewed Syria as a crisis-proof partner in the Arab world, which stood by Tehran during its 1980–88 war with Iraq, and the IRGC deployed large numbers of troops on Assad’s behalf in 2013. Russia viewed Syria as the last remaining pillar of its Soviet-era influence in the Middle East and as its gateway to the Mediterranean, but its historical experience with the Assad family brought back memories of alignment and profound disagreement. The main ideational bond between Russia and Iran was preventing a US-backed regime change in Syria, as both countries had previously viewed US-led military interventions in Kosovo, Iraq and Libya as threatening to international security.

In January 2014, Russia expanded its diplomatic cooperation with Iran by supporting Tehran’s presence at the UN-brokered Geneva talks on Syria. However, Russia was still wary about strategic collaboration with Iran in Syria, as it wanted to frame itself as an ‘honest broker’ between Bashar al-Assad and the Syrian opposition. IRGC Quds Forces commander Qassem Soleimani’s July 2015 trip to Moscow changed Russia’s perspective. During his consultations with Russian officials, Soleimani warned that Assad was on the verge of losing power and that rebel forces could occupy Syria’s Mediterranean coast. This paved the way for Russia’s first airstrikes on Syrian opposition-held areas in September 2015, which eventually strengthened Assad’s grip on power.

Russia and Iran: Partners or Competitors in Post-Conflict Syria?

Since 2015, Iran and Russia have agreed to a sustainable distribution of labour in Syria. IRGC forces played a decisive role in Assad’s triumphs in Aleppo, Dera’a and Deir ez-Zor and established strongholds in southern Syria but played a marginal role in Idlib and in resisting Turkey’s military incursions in northern Syria. Russia complemented the IRGC’s troop deployments with aerial support and Wagner Group private military contractors (PMCs), which provided logistical support and additional manpower to the Syrian army. Russia has also used its leadership role in the Astana Peace Process, which includes Iran and Turkey as co-guarantors; shuttle diplomacy with Israel and the Gulf monarchies; and its UN Security Council veto pen to strengthen Assad’s legitimacy. To complement these diplomatic forays, Russia has leveraged RT Arabic’s extensive reach in the MENA region to whitewash Assad’s war crimes and highlight Iran’s contributions to combating terrorism in Syria.

Once the Syrian civil war enters the ‘post-conflict’ reconstruction phase, Russia and Iran will almost certainly continue to support Syria’s return to the Arab League and undermine US Caesar Civilian Protection Act sanctions, which block foreign investments for reconstruction from entering Syria. However, the Syrian reconstruction process could exacerbate two areas of friction between Russia and Iran.

First, Russia is much more inclined than Iran to support comprehensive security-sector reform in Syria, as it believes that Assad relies less on personalist authority to attract foreign investment. These contrasting views on the necessity of security-sector reform could motivate Russia to strengthen its alignments with the Political Security Directorate and Iran to deepen its links with the Military and Air Force Intelligence bodies. This would exacerbate the already-uneasy state of civil-military relations in Syria. The growing presence of Russian and Iranian private security companies in Syria, which pursue disparate agendas, could make Moscow and Tehran’s frictions over security sector reform more acute.

Second, Russia and Iran might compete for reconstruction contracts in Syria. Russia’s early edge over Iran in the race for contracts in Syria’s real estate, phosphate mining and energy sectors has created periodic frictions with Iran. As Iran’s military intervention in Syria cost it $30 billion and Russia’s airstrikes cost $4 million a day, their desire to recover hard currency could exacerbate these tensions in a post-war environment.

While Russia and Iran’s disagreements over Syria are unlikely to jeopardise their broader partnership, they suggest that regional crises might emerge as an area of friction between the two countries. In Yemen, a similar trend of war-time Russian-Iranian cooperation and discord on final status issues is emerging. Since March 2015, Russia and Iran have been outspoken critics of the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen and both countries reject UNSC Resolution 2216’s imposition of sanctions on the Houthis. However, Russia recognises President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi as Yemen’s sole legitimate authority. This contrasts with Iran’s legitimisation of Houthi control over Sana’a, reflected through the appointment of Hassan Eyrlou, the country’s ambassador to Yemen.

As Bashar al-Assad aims to recapture control of Idlib and ensconce his regime’s hegemony over northern Syria, the Russia-Iran military alliance in Syria is transitioning into a competitive partnership. This trend could cause Russia and Iran to devote more attention to macro-level issues, such as reviving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), combatting the US’ unilateral sanctions, and compartmentalising growing disagreements on Syria and Yemen in the months ahead.

This is part of a series on the challenges and opportunities facing the Russian-Iranian partnership in the Middle East, based on contributions from participants in a closed LSE workshop in April 2021. Read the introduction here, and see the other pieces below.

In this series:

- The Russian-Iranian Partnership in the Middle East: Challenges and Opportunities by Ghoncheh Tazmini

- Russia’s Middle East Policy and View of the Post-Cold War Global Order by Viacheslav Morozov

- Drivers of Russia’s Middle East Policy by Diana Galeeva

- Russia and Iran’s Relations in Iraq by Arman Mahmoudian

- Russia and Iran in Syria: Military Allies or Competitive Partners? by Samuel Ramani

- The Post-Blockade Gulf: Prospects for Relations with Iran? The Russian Role by Courtney Freer

- Russia’s Role in Brokering a Comprehensive Agreement between the United States and Iran by Hamidreza Azizi

- Russia and the Issue of a New Security Architecture for the Persian Gulf by Nikolay Kozhanov

Thank you again for all the knowledge which you spread. i want for you to thank an individual within this awesome read! i really glad to visit again your website. Kalyan Matka