by Hashem Abushama

In her ground-breaking work Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Linda Tuhiwai Smith historicises the colonial knowledge/power nexus underlying Western knowledge production. She argues that research is ‘one of the ways in which the underlying code of imperialism and colonialism is both regulated and realized.’ Research is, therefore, enmeshed within the hierarchies of power produced by colonialism and imperialism. The production and circulation of knowledge between universities, in their different locations, forms and is formed by such relations. Such circulation, Smith reminds us, forms a ‘significant site of struggle between the interests and ways of knowing of the West and the interests and ways of knowing of the Other.’ Research is both a site of unfolding domination as well as a site of struggle against such domination.

Since January of this year, I have been involved as a Research Assistant with the LSE Academic Collaboration project ‘Neoliberal Visions: Exploring Gendered Adverts and Identities in the Palestinian West Bank,’ in collaboration with Birzeit University. Part of the project entails the development of a curriculum in Arabic that questions neoliberalism through gendered and sociological lenses. My role has been primarily to facilitate the translation from English to Arabic of academic texts that discuss neoliberalism and feminism. This circulation of knowledge – from one language to another, and from one university in England to another in Palestine – forms a site of struggle akin to Smith’s.

Having surveyed multiple databases in search for sources in Arabic relating to neoliberalism, I found few results. Those I did find were mainly in the field of political economy, examples being the Arabic translation of Adam Hanieh’s Lineages of Revolt: Issues of Contemporary Capitalism in the Middle East and a collection of lectures by the Mehdi Amel Cultural Centre on ‘the Arab Left in the Face of Global Neoliberalism.’ Another was the work by the Gulf Centre for Development Policies on the ‘Neoliberal Trap in the Arab Gulf Countries.’

These texts offer a generative starting point for critically analysing neoliberal capitalism in the region, which I understand as the latest manifestation of neo-colonialism and imperialism. Hanieh’s book, for example, frames Middle Eastern neoliberal capitalism as the product of both external and extractive domination as well as the region’s own social formations. His work is significant in that it avoids the trap of treating the region as a mere, passive object of external domination. In the particular context of the West Bank, Hanieh argues that the Palestinian Authority’s neoliberal economy is not an anomaly. Rather, it is a product of this dialectic between Western foreign intervention and Palestine’s own class formations.

Nonetheless, today we need to build on such political economy approaches in order to consider the messiness of everyday life and its enmeshment within the varying power relations. For example, Walaa Alqaisiya approaches the Israeli settler colonial order in Palestine as a ‘hetero-conquest,’ for it is a ‘desiring’ project that aims to eliminate the incapable Palestinian Other. She also argues that the neoliberal Palestinian Authority reproduces the taxonomies of this ‘hetero-conquest’. Alqaisiya’s analysis of the gendered nature of settler colonialism and its dependent Palestinian elites, coupled with Hanieh’s political economy approach, helps us shed light on the classed and gendered nature of neoliberalism.

It is by now established by many scholars that neoliberalism is a form of ‘governing rationality’ that governs all aspects of our society, including culture and ‘private’ life. Neoliberalism is intensely productive of social stratifications that are not only class-based, but also gendered and racial. There is, therefore, a necessity to map out how Palestine’s class formations inform and are informed by heteropatriarchal and racial neoliberal capitalism. The project ‘Neoliberal Visions’ aims to ask these questions. Rather than viewing these sociohistorical hierarchies as top-down structures, the project approaches them as lived relations that can be bent, adapted and disrupted. It is concerned with how class and gender are performed in everyday life, taking corporate advertisements as everyday objects that articulate such gendered and classed relations.

However, this raises questions about how we generate a discussion, or enrich the already existent conversations, in Arabic on the proliferation of neoliberal subjectivities in Palestine. If we choose to translate seminal texts from English to Arabic on this theme, which is what the project is doing, then what kind of questions does this raise on knowledge and power? What does this tell us about the hegemonic nature of English as a language, or what Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o terms in relation to African literature(s) as ‘the fatalistic logic of the unassailable position of English in our literature’? Furthermore, what does that tell us about translation? There are two reflections I want to offer upon this particular act of translation I have been involved in.

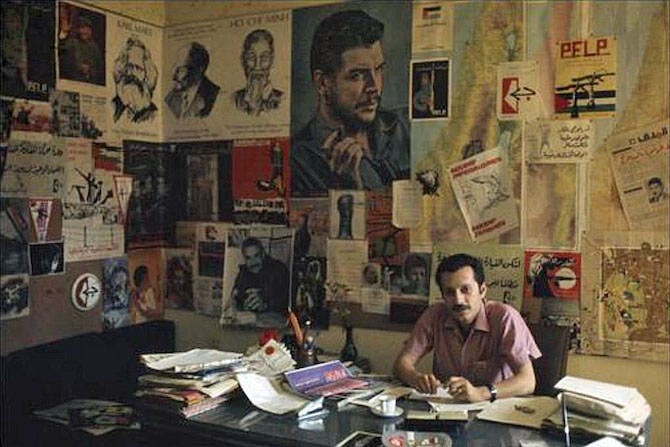

First, there is a tendency within the Western academy to view their many racialised Others as ‘raw data,’ or what Alexander Wehelieye describes as a tendency of ‘ethnographic detainment’. In other words, there is a tendency in Western academia to view knowledge coming from the Global North as universal, theoretical and applicable everywhere, whilst knowledge uttered from the Global South or minority discourse within the North is relegated to the realm of the ethnographic locality. For example, Wehelieye names the widespread use of theoretical formulations by Agamben and Foucault without interrogating the specific sociohistorical contexts from which they write as emblematic of this tendency. In the context of Palestine, there has indeed been a proliferation of Foucauldian and Agambenian analysis that does not question the specific context of Western Europe from which they write. In contrast, relevant theoretical writings by the likes of the Palestinian novelist and theorist Ghassan Kanafani and the Lebanese theorist Mehdi Amel have only recently been taken up as relevant theoretically. Their writings are often approached as mere sociological texts, and not necessarily as capable of generating a theoretical discussion on the specific nature of power formations in Palestine and Lebanon. In my reading of it, the limited and late translation of Amel’s influential work demonstrates that when translation occurs, it is often from English to Arabic and rarely vice versa. To translate a text from English to Arabic requires a disruption of this tendency, which we can do by bringing the text in critical conversation with the knowledge produced in the region.

Second, the one-sided circulation of knowledge from the Global North to the Global South is an extension of a colonial history and a neo-colonial present that posits French, English, Portuguese, and Spanish as the normative languages when it comes to knowledge production. Even the scarcity of normative knowledge production (books, texts, dissertations, etc., as opposed to the knowledge people weave and live in their everyday life) should, in my view, be understood through a lens that accounts for the structural de-development of the Arab World through colonial and settler colonial conquest, war, structural adjustment programs, scholarship conditions and curriculum imposition.

The first article we hope to translate, for example, pertains to neoliberal feminism. Neoliberalising feminism names the process by which liberal feminism ‘has gone to bed with capitalism.’ Rather than challenge the capitalist system, neoliberal feminism reproduces and expands its oppressive capacity. The translation of such a text into Arabic, and for a Palestinian university, requires us to examine the specific ways in which neoliberal feminism takes shape within the particular context of ‘hetero-conquest’ in Palestine. ‘Neoliberal Visions’ takes such questions seriously by exploring how, in their quest for profit, corporate actors in the West Bank instrumentalise feminist and resistance tropes. The translation of texts from English to Arabic is part of a wider project that raises questions about the specific settler colonial, neoliberal, gendered and classed capitalist power formations in Palestine.

This particular initiative to translate from English to Arabic is still significant in that it makes available seminal texts and further enriches already existent conversations on the oppressive nature of neoliberal capitalism. By contextualising the translations within a wider project attuned to power formations in Palestine, the project ‘Neoliberal Visions’ does not approach translation in a vacuum. Rather, in my reading of it, the project approaches ‘translation’ as a site of struggle. Nonetheless, the question of how this fits within a wider context of ‘neoliberal antiracism’ and neoliberal attempts to co-opt decolonial movements at British universities remains unanswered. Indeed, as Rahul Rao notes, such a conundrum opens up ‘a set of questions that are too big to confront within the confines of the university.’ These questions relate to the possibility for a genuine program of material and discursive decolonisation at universities in the Global North beyond limited programmes of collaboration.

This blog post is a product of the LSE Academic Collaboration project ‘Neoliberal Visions: Exploring Gendered Adverts and Identities in the Palestinian West Bank,’ in collaboration with Birzeit University.

هذا المقال متوفر باللغة العربية هنا

2 Comments