by David McDowall

Cambridge’s new history of the Kurds is a comprehensive and innovative edited collection, and though the quality varies over the 41 chapters, some brilliant contributions ought to be compulsory reading for all interested in Kurdish politics. David McDowall, author of the seminal Modern History of the Kurds, reviews for the blog.

The Cambridge Histories are a long-standing and highly distinguished series of essays on various countries, and an addition to this august canon which specifically concentrates on the Kurds, a stateless people, is greatly to be welcomed. All three of its editors are well-known and highly regarded in the field. They, in their turn, have called upon 38 other expert contributors to help write about various facets of the Kurdish experience. I naturally cannot mention them all by name, only those who particularly attracted my attention.

The editors have sought to escape the tyranny of the political borders which have divided Kurdistan since the 1920s by asking many of these contributors to look across these boundaries, which I think the editors see as barriers also to our thinking and understanding.

Boris James gets us off to an excellent start with his account of the rise and fall of the emirates in which he coins a word which aptly sums up the Kurds’ enduring political dilemma, whether we are speaking of the medieval Islamic world or the twenty-first century, ‘in-between-ness’. Situated between the great power centres of the Middle East, Kurdish leaders have always had to weigh two separate but interlocking matters (i) to which particular external potentate should a leader pay fealty and (ii) how loose can that fealty be rendered. If this was true when Kurdish leaders were sandwiched between Mamluks and Mongols in the fourteenth century, it was equally true for the Barzani leaders in September 2017 when their immediate neighbours reminded them so powerfully of their ‘in-between-ness’. In the subsequent five chapters we are shown the Kurdish emirates in their hey-day and their subsequent extinction. The emirs were seldom strong enough to repudiate an external overlord outright, but in choosing to whom to pay fealty, the principal consideration was probably not religious identity but physical distance from the seat of imperial power and the consequent inherent military difficulty an overlord might have in tighter control of his subordinates. Istanbul was much farther away (than Isfahan/Tehran) and therefore its control more tenuous. It suited Kurdish polities seeking maximum freedom of action to come to an arrangement that formalised the emirates vis-à-vis Istanbul.

Because Kurds have been victimised so frequently, it is easy to deplore the tightening of imperial control without taking fully into account how far the Ottoman and Iranian empires themselves felt acutely threatened by the European powers. Neither could afford to indulge local autonomies, since these weakened the ramparts of empire against European appetites. The early intimations of Kurdish national identity seem to be a response to the growing heavy-handedness of Istanbul and Isfahan, itself impelled by fear of Europe. The utterances of Sheikh Ubeydullah continue to mesmerise those looking for early evidence of nationalism. Djene Rhys Bajalan views him as an early nationalist but acknowledges that others contend that conclusion (p. 104). Kamal Soleimani sweeps such sceptics aside, Ubeydallah’s nationalism being ‘unquestionable’ (p. 140), based upon his words rather than his actions. I doubt this particular debate will end any time soon. Soleimani is right, however, to show how disentangling religious and national sensibilities risks misunderstanding the behaviour of many actors for whom the two were (and, for some, still are) inevitably enmeshed.

As the Ottomans incompetently sought to incorporate Kurdistan more firmly, Kurds can easily feel this amounted to deliberate erasure of their culture and well-being. While economically damaging, I’m not convinced that Istanbul ‘aimed at severing an important link between historical memory and the people’ (p. 97). Eradication of the emirates was not an act of gratuitous spite. I also doubt the Ottomans intentionally damaged Kurdistan’s economy. They were equally clumsy, incompetent and destructive elsewhere.

One can also perceive the sense of betrayal Kurds feel with another lightning rod of identity, the Treaty of Sèvres, which attracts far more attention than it deserves. In reality it was a non-event. The Ottomans never ratified so distasteful a deal, while Mustafa Kemal’s rebellion rendered it entirely academic. In any case, Britain itself, which drafted the relevant articles, 62 and 64, remained uncertain as to its true intention beyond keeping the Turks away from Mesopotamia’s northern approaches. Any realisation of Sèvres hugely depended upon Kurds themselves being pro-active, which understandably they were not because (i) like other players, they could not tell which way the political winds were blowing, nor (ii) could they be sure the Europeans would not hold them to account for the Armenian genocide; and (iii) because, being tribally organised, they were deeply riven by internal rivalries.

The most valuable piece in Part I is Veli Yadirgi’s elegant essay on the political economy of Kurdistan which, like his ground-breaking book of similar title, sets out in great clarity a compelling economic account of the progressive de-development of Kurdistan from the Tanzimat (mid-19th century Ottoman reform) period onwards. Despite his splendid contribution, economic history remains, in my view, a Cinderella in Kurdish studies, with probably much more to be gained from further studies, with wider angle to take in the economic impact of the Great Powers and also with much narrower focus on specific localities at specific junctures.

The following two parts, ‘Regional Political Developments’ and ‘Domestic Political Developments’, both covering the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, are in my view less successful. While there is valuable material on Kurds in all four states, there are many junctures at which crucial points seem to be missed. One can see the intention of teasing out domestic from regional matters, but so-called domestic developments within Kurdish society are inextricably interwoven with state policy within the confines of the particular post-1918 polity in which Kurds found themselves. As a consequence, instead of coherence in showing how regional and Kurdish domestic matters interacted, what we have is sometimes patchy, episodic and missing important facets, while other events and developments are discussed in repetition, first as a regional phenomenon, secondly as a domestic one, with insufficient consideration of wider ramifications. For example, the almost genocidal suppression of the 1925 Shaikh Said rebellion fed directly into the League of Nations award of the vilayet of Mosul to Iraq in 1926, which Turkey had badly wanted but casually threw away by its own conduct. Meanwhile, the suggestion that the rebellion failed because it ‘was not supported by urban Kurds and that neither Britain nor the USSR was in favour of an independent Kurdistan’ (pp. 314-15) does not bear scrutiny. Britain, for example, would have been delighted with a stable Kurdistan as a buffer between the new Turkey and Iraq. That is exactly what they had unrealistically hoped for at Sèvres. But they certainly weren’t going to provide troops for a so obviously unwinnable a war, with or without urban Kurds. Sheikh Said never had a chance. Given its weaponry, discipline, telegraph and railway, Ankara could always concentrate its forces at any given point in greater strength and at greater speed than could poorly organised and poorly armed tribesmen. (Mehmet Kurt is also quite right to say that other tribes undermined the revolt (p. 509). Speaking of missed points, like the League of Nations award, the Treaty of Saadabad (1937) receives no mention, yet it formalised the enduring joint policy of Turkey, Iraq and Iran (and one can also include the non-signatory Syria) permanently to deny Kurdish separatism. With the exception of Turkey, they have each used Kurds as a cat’s paw to foment unrest for a neighbour while simultaneously deprecating an independent Kurdish polity. This position, the curse of ‘in-between-ness’, remains permanently crucial.

There is sometimes, too, a tendency not to see the wider picture, why regional or great powers act in the way they do. Syria’s persecution of its Kurdish minority was not simply racial prejudice. True, in part it was driven by centuries of perceived ‘trouble’ with Kurds. But by the 1950s Arab Syria felt unutterably weak, emerging from French imperial control and surrounded by genuine foes. It had sound reasons for its sense of weakness and its paranoia in the light of the constant threat posed by Israel and the United States (and potentially by Turkey, its NATO ally, which had already bitten off the sanjaq of Alexandretta (Hatay) in 1939), and it sought strength through the charismatic emergence of Arab Nationalism led by Nasser. Within this wider context, Syria’s fear that its Kurds were a potential Trojan Horse was not groundless. We all know that fear begets some extremely bad decisions, be it in public or personal life.

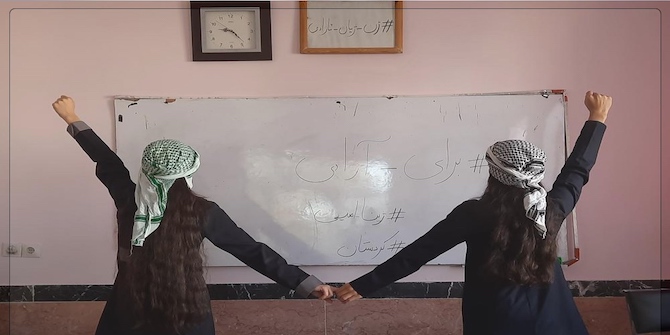

Where in all Kurdish studies is the Kurdish street? Historians frequently neglect discussion of the lives of ordinary people, so Nicole Watts’ perceptive chapter on street protest and opposition to the controlling elite in Iraq is particularly welcome, calling ‘our attention to the agency of people who are not necessarily active in parties and political associations’ (p. 402). As with economic studies, we need far more study of ‘the worm’s eye view’ of what has been going on, be it in any of the states in which Kurds find themselves, since it will inform so much regarding Kurdish society. Since the rise of social media and digital publishing we can hope for much more information from the streets of Kurdistan, as well as its diaspora.

Notwithstanding my reservations about Parts II and III, Part IV (‘Religion and Society’) provides an extraordinarily valuable contribution to Kurdish studies. Here we are in very good hands indeed. Michiel Leezenberg notes that, ‘Among secular Kurdish nationalists, and in the foreign media, one may find a persistent (self) image that the Islamic faith is less widespread and less deeply rooted among the Kurds than among their Arab, Turkish and Persian neighbours…..On closer inspection, things appear to be rather more complicated: religion has always played, and continues to play, a rather greater role in Kurdish public and private life than admitted by secular nationalists’ (p. 477) and, one might add, secular academics. His chapter, and those that follow, are brilliant correctives to this secular image. Mehmet Kurt writes on the complexity, interplay and conflicts between different Muslim traditions and Turkish and Kurdish national identity. He is a trusty guide. As he concludes, ‘the rise of Islamist civil society in Turkey in general, and the Kurdish region in particular, has brought religious beliefs, commemorations and discourses at [sic] the core of the public sphere.’ (p. 529) I must count myself among those guilty of giving the Islamic dimension insufficient space. Philip Kreyenbroek, Khanna Omarkhali and Erdal Gezik then take us by the hand through the labyrinth of religious minorities telling us much about them and their inter-connectedness which I, for one, did not understand so well before. There is much to absorb here, and much to remind us that simply writing about ‘the Kurds’ risks being dangerously simplistic. Religious identity, in all its variety, complexity and ambiguity, demands our attention.

In chapter 23 Hamit Bozarslan and Cengiz Gunes assess the roles tribes have played and how these roles have evolved, including an acknowledgment of their generally declining political power, except where they are able to exploit the lucrative Village Guard system. This chapter should be compulsory reading for all interested in Kurdish politics. However, the authors do not discuss when, as elsewhere in the world, tribal chiefs have managed political decline by the investment of effort, influence and resources in economic and social spheres, something described by Anna Grabolle-Çelika in her outstanding book, Kurdish Life in Contemporary Turkey (2013), and something which cries out for study in the case of the tribal chiefs of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq: how far chiefs can retain dependents and clients through economic and social means.

Part 5 explores Kurdish language in its manifold dialects, including Kurmanji (the northern dialect, central Kurdish (often called Sorani), Kirmanjki (which outsiders usually call Zazaki, but is also known by other names within the region). Again, for non-speakers, these chapters convey the complexity of dialect and identity, not to mention the implicit political difficulties in confronting the state.

Part 6 includes essays on poetry, the new (Europe-derived) forms of literary and artistic expression: novels, theatre and cinema. Since few Kurds have the reading habit, cinema remains potentially the most influential medium, and we have a reliable guide in Bahar Şimşek. With regard to visual art, perhaps a few exemplary illustrations would have been helpful.

Part 7 is entitled ‘Transversal Dynamics’, a baffling title until one has read its contents. Joost Jongerden and Hamdi Akkaya draw attention to the slow emergence of two Kurdish political camps, both present in the Mahabad Republic, 1946-47, but today seen in their starkest forms in the conservative Barzani ‘camp’, which dominates the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, and the radical Öcalanist approach expressed in the pro-Kurd civil movement in Turkey and by the Syrian Democratic Council in northern Syria. Ever since the first salon gatherings in Istanbul in the early 1900s, leaders have been divided between secessionists, autonomists and integrationists. We need not worry ourselves about the latter for they have embraced the mainstream culture of the state they are in, but the other two still compete for support. It is perhaps an irony that the Barzani ‘secessionists’ are now firmly saddled with autonomy as Iraqis, while the autonomy that Syrian Kurds currently enjoy is likely to prove temporary.

Chapters 33 and 34 cover questions of displacement. The former discusses ‘Kurdish Transnational Indigeneity’ which, as its author admits ‘is, at first sight, an oxymoron.’ (p. 829). I’m not entirely convinced that she has successfully made her case that it is not. Migrants are compelled by the very act of displacement and the new – usually urban – conditions in which they find themselves, to reassess their identity. Some simply integrate, but those who seek solace in the identity they believe they carry almost invariably reconstitute it in a fundamentally modified, usually more virulent form. I saw this at first hand over 40 years ago in the civil war in Beirut, where erstwhile villagers of different faiths, who had much more in common with each other than differences, nevertheless reconstructed their identity in the urban slums to marshal their solidarity based on confession, not class, and then went to war. The migrant experience can and does indeed feed back into the indigenous society, as chapter 34 traces, something that undoubtedly has impelled Kurdish nationalism in its development, but it is no longer itself indigenous but more the product of a mix of experiences and political thought, even for those who imagine they have achieved a purer essence to their identity.

It is unfortunate that we must await until the last two chapters of the entire book to look at the 50 per cent component of Kurdish society: women and girls. I don’t think I’d have ever guessed they constituted a ‘transversal dynamic’, as opposed to a crucial half of the Kurdish demographic, hence more properly discussed in Part IV (discussing society). For my money, Isabel Käser’s chapter, against some stiff contenders, is the most brilliant contribution to this volume and therefore doubly unfortunate it should be situated at the very end. While I’m sure the editors did not intend to downplay the gender dimension of Kurdish society (and politics), they have unwittingly done just that. Every page of Käser’s contribution contains revelatory insights which I wish I had read before myself trying to write – blindfolded, it now feels – about gender. So, if you read nothing else, go straight to page 893.

Reviewing the book as a whole, it is inevitable that with a total of 41 contributors the quality is uneven, as also must be the degree of interest the reader will have in each and every article. Some are written in lucid English, but a significant number are not. This is where the publisher’s own copy editors should have worked closely with the academic editors to ensure good prose throughout, replacing recondite words (I found myself having to search for word definitions not even in the OED and only available on the internet), and redrafting the impacted abstruse phraseology of academe with simple wording. Frankly, if it cannot be said in simple English it is almost certainly not worth saying. There is also in places a certain amount of extraneous descriptive material with no real relevance to the argument in hand that could usefully have been excised. I also think it was a mistake to impact within the text bracketed references to other academics’ work, sometimes in spaghetti-like strings, quite often wholly unnecessary self-justification (OK for a doctoral dissertation perhaps, but if absolutely necessary in a book of this kind, better tucked at the bottom of the page as footnotes). Ease and clarity of reading should be an absolute priority. The publishers should have insisted on this. We should want Kurdish studies to welcome newcomers with an open door, not lurk behind serried barricades of arcane academe. So, I end with a plea that such books should be written in good plain prose, using words in common usage, as if those of us who write such material have in our mind’s eye how we would tell a friend unversed in Kurdish affairs over a drink what we really want her or him to know and understand. And more maps, please!

FYI

Enclosed link below

https://sotkurdistan.net/2021/09/03/%d8%aa%d8%a7%d8%b1%d9%8a%d8%ae-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%83%d8%b1%d8%af-%d8%b9%d9%8e%d8%b1%d8%b6-%d9%88%d8%a7%d8%b9%d8%af%d8%a7%d8%af-%d8%af%d9%8a%d9%81%d9%8a%d8%af-%d9%85%d8%a7%d9%83%d8%af%d9%88%d9%8a/ ;

Dear Mr. David McDowall,

I am in the process of translation your entire review into Arabic. Excuse my ignorance, but would you kindly elaborate on the term “august canon” for correct and accurate rendering.

Regards,

Muhamad Tawfiq Ali

(FCIL.CL)