by Allan Hassaniyan

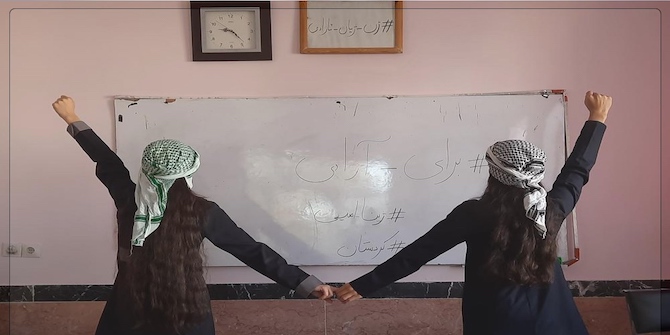

Iran’s widespread uprising, which was ignited by Kurdish protests against the Iranian security forces’ brutal murder of the 22-year-old Kurdish woman Jina Amini on 16 September 2022, enters its sixth week. These protests are growing day by day, and have become more diverse and inclusive in terms of participants’ backgrounds and geographical locations. They challenge the Islamic regime’s core values and symbols, including the authority of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. A countrywide call for regime change is now among the main features of the uprising. Women and men have joined forces in shouting ‘Jin, jiyan, azadi‘ (woman, life, freedom), a slogan of the Kurdish movement (representing its distinctive approach to gender equality) and ‘death to the dictator‘ – both tying together protest demands across Iran.

The security forces have disproportionately used, and rapidly escalated, violence to crack down on protests. Such excessive use of violence, including live ammunition against protesters, has been taking place in Iranian provinces such as Kurdistan, Sistan and Baluchistan, which have ethno-religious differences from the ruling regime. Indeed, these provinces have a deep history of resistance against the Islamic Republic and its value system, and have long been militarised by the regime. On Friday 30 September, security forces used a fighter helicopter against the protests in Sistan and Baluchistan, killing around 100 protesters in the city of Zahedan, on a day that is already known as the Black Friday of Zahedan. The regime has attempted to justify this attack as a necessary way of dealing with troublemakers and separatism. The Black Friday of Zahedan is an indisputably aggressive and excessive act of warfare; an atrocity and a display of disproportionate violence that states rarely use in their domestic affairs.

Historically, and under the pretext that the demands of non-Persian Iranians for inclusion, equal citizenship and fair power sharing pose a threat to Iran’s territorial integrity, minority groups, including Arabs, Azeris, Baluchis, Kurds and Turkmens, have suffered under the Islamic Republic and the preceding Pahlavi regime. Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the peripheral regions of Iran have been sites of violence and state coercion, as different ruling regimes attempt to suppress dissent. When these groups denounce the Islamic regime’s discriminative policies, they are labelled as separatists and troublemakers. Such discriminatory treatment of minorities is not limited to the government and its institutions. It is also visible among diasporic Persian communities, particularly in instances where they react in outrage when non-Persians engage in debates about the identity and rights of subaltern groups in a post-Islamic Republic Iran. Like the regime, some accuse these minorities of separatism. In recent weeks, the demonstrations across the diaspora, in support of the nationwide uprising, have featured some conflict and clashes between Persian and non-Persian Iranian nationals. Pan-Iranist and monarchist protesters felt provoked by Kurds waving the Kurdish flag during protests across the United States and Europe.

The Iranian government has attempted to diversify its strategies for quashing the uprising. Labelling civilian protests as armed revolts, and even deliberately attempting to turn them into such, has been among the regime’s tactics. This serves multiple ends, and its implementation relies on multiple measures. Spreading fake news about the protests in Kurdistan, Sistan and Baluchistan, and referring to them as ‘separatist activities’, are methods deployed by the government to disturb and destroy Iran’s nascent intercommunal unity and solidarity. By labelling protests in peripheral regions such as Kurdistan, Khuzestan, Sistan and Baluchistan as separatist armed revolts, the regime hopes to sway public opinion in its favour, particularly in the central regions and provinces of the country, which are populated by the dominant ethnic group, many of whom argue that without the Islamic Republic, the territorial integrity of Iran would be endangered.

Indications of the government’s attempt to turn the uprising into an armed revolt became particularly evident during the second week of the protests. The regime systematically disseminated fakes news and videos about the presence of members of Kurdish armed groups, namely the Peshmerga (the military wing of Kurdish political parties), among the protesters. Videos circulated around social media, showing members of the Iranian security forces dressed as Peshmerga, harassing locals in Kurdish cities. The regime has also attempted to force the actual Iranian Kurdish Peshmerga, with their bases in the mountainous areas of Iranian and Iraqi Kurdistan, to return to urban areas and join the protests. This tactic, seemingly at odds with the Iranian government’s decades-long campaign to destroy Kurdish resistance and militarise the Kurdistan province, serves the regime’s agenda of responding to the uprising with full, brutal force under the banner of preserving national security.

Successfully labelling the uprisings in Kurdistan, Sistan, Baluchistan, and other peripheral areas of Iran as armed revolts would benefit the regime, both domestically and internationally. Such a discursive distortion would be used to justify the Islamic regime’s brutal suppression of the protests in these regions. In a fragmented society such as Iran, intercommunal distrust between Persian and non-Persian communities is deeply rooted and arguably weighs heavier than the emerging forms of solidarity that have been forged since the death of Jina Amini on 16 September 2022. The days and weeks ahead will reveal whether this solidarity has truly taken root.