by Nicola Degli Esposti

The Kurdish people are most often described as the world’s largest stateless nation. The phrase is indicative of the way we tend to look at the Kurds, which is, almost exclusively, through the prisms of nationhood and (denied) statehood. In recent years, the Kurds have enjoyed an unusually high degree of international media attention thanks to the role of Kurdish groups from Syria and Iraq in the war against ISIS, which raised worldwide sympathy for their national cause. In the same years, growing instability in the Middle East allowed for the establishment, in Syria, and consolidation, in Iraq, of two semi-independent Kurdish regions with their institutions and armed forces, an absolute novelty in modern history. Yet, despite this momentous advance, the Kurdish movement is more divided than ever, and competition overshadows cooperation to the point that Kurdish groups from one country are often allied against those of another and with regional powers that oppress ‘their own’ Kurdish minorities. The rivalry and distrust between the dominant Kurdish forces of Iraq and those of Turkey and Syria are so deep that working together to build a Kurdish state is almost unthinkable. In my book, Nation and Class in the History of the Kurdish Movement (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), I search for the origins of these divisions in the century-old history of Kurdish nationalism. The main finding of my research is that the different social origins of the dominant Kurdish parties, particularly those of Iraq and Turkey, shaped competing and irreconcilable national projects.

The Social Origins of Kurdish Nationalism

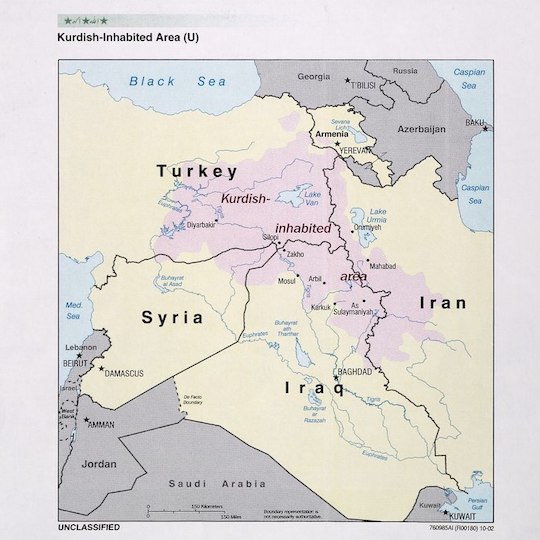

The Kurdish National Question dates back to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the partition of Kurdish lands between the new nation-states of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran (see Map). In each of these countries, the Kurdish traditional ruling class composed of tribal (Agha) and religious (Shaykh) leaders, revolted against the modernisation and nation-building projects of the new states but were, with no exception, defeated. Yet, not in the same way. Monarchical Iraq, a British colony, was more accommodating to tribal authority and Kurdish revolts were marginal and episodical. The Kurdish tribal elite, alongside the Arab, was eventually integrated into the new state and allowed to grab tribal and communal land that gradually turned it into a class of huge landowners. In Kemalist Turkey, major Kurdish revolts were violently crushed and followed by massacres and deportation while tribes were largely disarmed. Only by the 1950s, Kurdish tribal chiefs and landlords were gradually integrated into Turkish politics due to their control over rural constituencies but had to renounce any public display of Kurdish identity.

The Kurdish movement in Iraq re-emerged after the republican revolution of 1958. The land reform issued by the revolutionary government pushed many landlords to join the Kurdish revolution of 1961 led by Mustafa Barzani, himself a member of the traditional class. This type of leadership marginalised both the demands of the peasantry and the progressive urban classes, giving Kurdish nationalism in Iraq and its dominant force – the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) – a long-term conservative character. The Kurdish uprising in Iraq lasted until 1991 when a no-fly zone imposed by the United States allowed for the establishment of a Kurdish autonomous region dominated by the KDP and its main rival, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). In Turkey, the Kurdish movement was to re-emerge in the 1970s but with opposite class bases. It was radical students and teachers, coming from villages but politically educated in Turkey’s metropoles who started the Kurdish revolution. The strongest party that emerged, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), set itself to mobilise the Kurdish peasantry by directing its action not merely against Turkish gendarmes but also exploitative (Kurdish) landowners and aghas. The support of the peasantry allowed the PKK to lead an insurgency that, in the 1980s, posed a serious challenge to the Turkish state.

The social structure of both regions was profoundly shaken by the counter-insurgency strategies deployed by the two states between the 1980s and 1990s. First, Saddam Hussein’s army and, soon after, the Turkish military worked to depopulate the Kurdish countryside through mass killings, deportations, and the burning down of thousands of villages that provided indispensable logistics and manpower to both insurgencies. These strategies led to the de facto destruction of the Kurdish peasantry as a social class in both Turkish and Iraqi Kurdistan. These transformations turned millions of peasants into urban poor irreversibly changing the class structure and human geography of the two regions. In the rentier economy of oil-rich Iraqi Kurdistan, newly-urbanised peasants were kept unproductive and dependent on public handouts, forced to rely on patron-client relations with local warlords and politicians. In Turkey, ex-peasants filled the labour-intensive factories that constituted the backbone of the country’s recent industrialisation.

The Long History of the Present Divide

We cannot understand Kurdish politics today without appreciating these transformations. In Iraqi Kurdistan, popular discontent against the kleptocratic Kurdish elite emerged repeatedly in the 2000s and exploded in 2015, when the collapse of oil prices and the war on ISIS shook the redistributive capacity of the rentier system. Since then, the electoral turnout has collapsed, and mass revolts have taken place regularly targeting the regional government and forcing the KDP to rely on an aggressive form of Kurdish nationalism that led to the disastrous independence referendum of 2017. In these terms, the main political dynamic in Iraqi Kurdistan is a people-versus-elite divide, closely resembling recent political processes in Arab Iraq. In Turkey, the support that the PKK enjoyed in the mountain villages transferred to the new shantytowns, brought by the deported villagers themselves. This process allowed the legal Kurdish parties to gradually ‘conquer’ townships and municipalities throughout the Kurdish region and build up a strong urban power base.

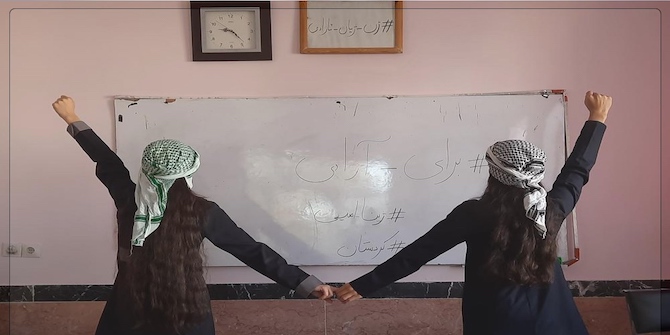

Similar transformations were also at work in the Kurdish regions of Iran and Syria. In the latter, the long-term presence of the PKK and the profound ties that link Turkish and Syrian Kurds allowed for the growth of the PKK-sister party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD). The establishment of an autonomous Kurdish region in Syria (Rojava) by the PYD in 2012 and the marginalisation of the local pro-KDP parties have significantly intensified tension between the two emerging Kurdish transnational blocs: the KDP-led bloc ruling Iraqi Kurdistan and the PKK-PYD, hegemonic in Turkish and Syrian Kurdistan, pursuing alternative projects for the future of the Kurdish nation. As I tried to explain here and in the book, this division is not the result of a mere struggle for power but is instead based on different class forces that have their roots in the conflict of Kurdish rural society in the twentieth century.