by Toby Dodge

Iraq’s sixth national elections since regime change in 2003, held on 10 October 2021, took place against a background of intense political instability. The governing elite’s violent suppression of the ‘Tishreen revolution’, from October 2019 onwards, forced the resignation of the Prime Minister, Adel Abdel-Mahdi and the appointment of a new temporary Prime Minister, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, and temporary government.

The low voter turnout, at 43 per cent, was no surprise and represented the continuation of a long-running post-2005 trend. The majority of Iraq’s population, alienated from a de-legitimised, violent and corrupt ruling elite, once again turned their backs on a democratic process that has repeatedly failed to deliver meaningful change in who or how the country is governed.

The main surprise was not the election itself, even though it was contested under a new electoral system, but the on-going inability of the ruling elite to find the consensus needed to form a government in its aftermath. Although the results of every national election in Iraq since 2005 have been contested and allegations of voter fraud tested in the courts, the on-going contestation of the 2021 elections has utilised intra-elite violence and has seen parts of Iraq’s political elite attempt to rework the long-established norms, the Muhasasa Ta’ifia, that has shaped government formation since regime change. This bold attempt at changing the unwritten rules that have underpinned Iraq’s governing system was all the more surprising, given that the votes cast, as opposed to the seats won, for the main protagonists were evenly balanced, giving no one party the upper hand in voter preferences nor electoral legitimacy.

These two, interlinked, blog posts will examine the elections and their aftermath, the contestation of the results and the ramifications of the long-running stalemate in government formation that has followed.

Although the end result will ultimately be another government of national unity, the violent contestation of the electoral results and the controversial role played by the Federal Supreme Court, all indicate a sustained challenge to the intra-elite consensus that has under-written the functioning of Iraq’s political system since 2003.

The 2021 Electoral System and the Results

One of the many demands of the Tishreen protestors was a complete overhaul of Iraq’s electoral system. These new rules were passed by parliament with surprising speed and divided the country into eighty-three electoral districts, with three to five candidates elected in each through a single non-transferable vote system. Adherents of the new system argued that a parliament made up of directly elected members would be more responsive to those who voted for them. The removal of a proportional party list system was meant to reduce the central power of party bosses and increase the ability of the previously incoherent and hence supine Iraqi parliament to hold the executive to account.

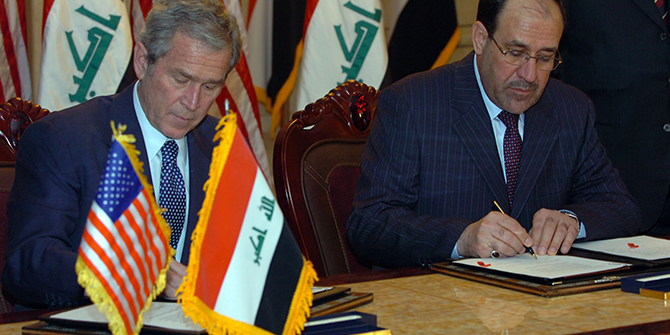

In reality, the unchallenged power of the elite that dominates Iraq’s political system means the newly elected parliament is acting, once again, as a tool for the machinations of party bosses, proving that optimistic claims about the new electoral system were misplaced. The bigger surprise delivered by the new electoral rules is how they favoured centralised and disciplined political parties, those run by Muqtada al-Sadr, Nuri al-Maliki and Mohammed al-Halbousi, over and above the more organisationally diffuse multi-party coalitions, which have since 2005 been the traditional vehicle for electoral mobilisation.

On first reading, the Sadrist’s 73 seats, Halbousi’s 37 and Maliki’s 33 looks like a set of unambiguous election successes for all three. This is especially the case with the Fateh Coalition, who represent the Iranian-aligned militias, only winning 17 seats, down from 48 and second place in the 2018 elections. However, a closer examination of the voter tally for each group, as opposed to the number of seats they gained in parliament, shows a different set of voting patterns, a dynamic that none of the major parties can take much optimism from. First, there was a marked decline is general support for all of the major competing parties, with the Sadrists, for example, losing a total of 608,000 votes, in comparison to their 2018 tally. Secondly, the electoral strategies of the winning parties, combined with the single non-transferable vote system, amplified their victories, in terms of seats won, way beyond the votes they actually received. This dynamic is not only most pronounced for the election victors, the Sadrists, but also its losers, Fateh. In spite of the 73 to 17 seat difference between the two, the total national votes cast for each actually favoured Fateh, who won 670,000 votes to the Sadrists 650,000. Across Baghdad and the south of Iraq, the Sadrists triumphed at the expense of Fateh because they astutely grasped the dynamics of the new electoral system and had the internal party discipline to deploy single and locally popular candidates where Fateh split their vote amongst multiple candidates. The Sadrist victory, despite being built on a weak electoral showing, encouraged hubris amongst the movement’s senior leadership and motivated them to pursue a set of maximalist demands.

The overall decline in the popular vote, partly shaped by an active voter and candidate boycott in the face of a violent campaign of candidate intimidation and murder, combined with a more evenly spread voter tally between the major parties, calls into question the significance of the elections and, more importantly, what popular mandate, if any, the winners, especially Sadr, can claim from its outcome. The unrepresentative parliamentary arithmetic, with the mismatch between votes cast and seats won, shaped how the various parties reacted to the election result. It also, over the longer-term, further undermines the role of parliament in Iraq’s political system, once again marginalising the influence of the country’s elected representatives as the long-discredited party bosses squabble about how the assets of the state are divided amongst themselves as a reward for their participation in the system.

This is Part 1 of a two-part blog series on the aftermath of the 2021 Iraqi elections. Read Part 2 here.