by Sara Abdellatif, Rasha Kaloti, Fouad M. Fouad & Adam P. Coutts

The case of Lebanon has demonstrated how multiple man-made and (specifically) politically driven crises that have enveloped the country have created a failed state, social chaos and a public health disaster. The socio-political miasma of hyper-inflation, wage devaluation, extreme poverty, Covid-19, and increasing security risks has fractured the health system.

The massive Beirut blast which hit the city in August 2020, resulting in the death and injury of thousands, left vital infrastructure destroyed including healthcare facilities. Consequently, the healthcare sector has been struggling to cope with the increased demand, and the aftermath of these crises’ effects on it continue to manifest. Thousands of citizens and health workers have left the country, leaving key public services even more weakened.

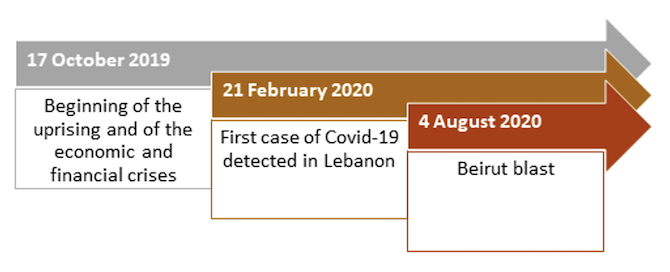

The health sector has long been viewed as fragile, fragmented and inequitable, but in the past two years, the country faced an unprecedented multi-crisis situation. The financial crisis which reached its height in 2019 caused an economic and financial collapse. The Covid-19 pandemic added further stress to an already stretched healthcare system.

Overview of the Lebanese Healthcare Sector

The healthcare system in Lebanon has been greatly influenced by the conflicts of the country’s recent history. The 1975–90 Civil War devastated the sector, with the situation then compounded by political unrest over the years since and the Syria crisis that began in 2011. Today, inequity, sectarianism, fragmentation, and privatisation characterise this sector in Lebanon.

The primary healthcare centres are mainly operated by Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) through agreements with the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH). However at secondary health care services, the majority of hospital beds (86%) are provided by the private sector. Out of pocket payments remain the main funding source in the Lebanese healthcare system. Population groups access healthcare services differently and at various levels of social protection.

For example, Syrian refugees access the MOPH primary healthcare services through subsidisation from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and NGO healthcare facilities. On the other hand, Palestinian refugees access primary healthcare services provided by the United Nations Relief and Work Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), with some subsidies provided by this agency for hospital care at NGOs or private hospitals. This has generated accessibility constraints for these populations who suffer from financial difficulties, as do vulnerable Lebanese populations and Lebanese returnees from Syria.

The Lebanese Healthcare System within Multiple Crises

The Lebanese economy began to witness a decrease in the influx of capital in 2011. A decade later, in fall 2019, Lebanon experienced a full-fledged financial crisis as the economy crashed. Since then, the Lebanese Lira has been depreciating, leading to hyperinflation and the loss of people’s savings and livelihoods. Bank-enforced informal capital controls on businesses and depositors’ funds caused difficulties in importing medical equipment and medications, while many were unable to pay their medical bills. It also weakened the healthcare sector which was already lacking in resources, with the Lebanese government incurring an estimated debt of 1.3 billion USD to private hospitals in 2019.

Meanwhile, since October 2019, the country has lost about 40% of its doctors and 30% of its nurses to emigration. Along with the ongoing fuel shortage and power cuts, the healthcare sector was hit once more in November 2021 with the lifting of subsidies on medication, rendering them inaccessible to numerous residents, including those reliant on lifesaving medicine.

The arrival of the Covid-19 virus further jeopardised the country’s healthcare sector. The government resorted to implementing strict nationwide lockdowns four times to face this incoming threat. Nonetheless, the public’s distrust in the Lebanese government (reported at 94%) reduced their compliance with public health and safety measures. Subsequently, the country has recorded over 1 million COVID-19 cases as of 5 April 2022, which during the peaks challenged hospital capacity and overwhelmed the system.

Less than a year into Lebanon’s Covid-19 and economic crises, Beirut was shaken by one of the most powerful non-nuclear explosions in modern history on 4 August 2020. This blast took the lives of 220 people and injured 7000 more. The blast also hit the medical sector with half of the capital’s healthcare institutions out of service.

The Pathway Forward

Lebanon’s case illustrates the impact of years of political instability on the healthcare system’s resilience in crisis situations. The political and economic vulnerability of the country has resulted in a reduced ability to withstand further crises, such as the Covid-19 pandemic and the Beirut blast. This has in turn crippled the already weak healthcare system, with dire consequences for public health.

In order to safely exit the multi-crisis situation, the new Lebanese government should establish robust healthcare reform plans, led by the MOPH and in collaboration with relevant ministries to address the rising challenges in the country. The reform plans should be in coordination with all healthcare stakeholders in Lebanon, whereby Private-Public Partnerships (PPPs) are put in place and healthcare needs are covered based on urgency. Finally, setting a clear and concise crisis exit strategy is crucial, with exiting the financial crisis – a core determinant of the current state failure – is prioritised.

Watch a video summarising the new report this blog introduces, ‘Lebanon on Life Support: How Politics Made a Nation Sick’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bju0v70ZgIk

1 Comments