by Eman Javaid

‘El Shari Lina!’ (‘The Street is Ours!’) was a popular slogan during the Egyptian revolution of 2011 and yet most of the academic scholarship and post hoc analysis of the event places an immense importance on the role of social media and the transnational element, masking the urban spatial politics which helped to drive the revolution. Western sociology has a tendency to analyse social movements using theories built in the context of liberal democratic societies, whereas there is a need to highlight local political expression in autocratic regimes like Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt. Asef Bayat, an Iranian-American sociologist, defines the Egyptian state as a marriage of autocratic polity with a neoliberal economy. In such a climate, the costs of political participation are exceptionally high.

The Egyptian revolutionary struggle cannot be located on a map, a calendar or a set of social media pages. It was ongoing resistance against state power and this blog attempts to highlight the weapons that civilians, facing a powerful autocratic regime, employed to undermine it. The role of social media and the middle classes in the revolution having been the subject of extensive research and coverage, this blog will focus instead on the role of the urban poor as the drivers of the revolution.

The revolution arguably started not in 2011, but after the death of Khalid Saeed at the hands of Alexandria police on 6 June 2010. He did not belong to any religious or political group and was just an average person frustrated with his financial conditions and the economic policies of the regime, as were many more millions in Egypt. Perhaps one reason this particular case of police brutality gained so much attention was that many Egyptians identified with his plight and background. That same year two other major events took place which had immense implications for the revolution: the rigged elections and the mid-winter spike in the price of bread. In nearby Tunisia, a street vendor named Muhammad Bouazizi set himself on fire and sparked the Jasmine Revolution, with this event igniting anger and hope among Egyptians that the same could happen for them.

It is worth highlighting the two distinct demographics who featured in the key events above: the urban poor and the middle classes. The middle classes and the youth were mostly responsible to the social media uproar and the mobilisation of people through the use of these ‘spaces of flows,’ as described by Manuel Castell’s Networked Social Movement theory. However, the role of the urban poor, including street vendors, was much more muted and subtle, though it proved to be essential to the cause of the revolution.

Bayat names the acts of resistance by the urban poor as ‘social non-movements,’ referencing Charles’s Tilly’s Social Movement Theory which deems public vocal expression in large numbers as a pre-requisite for social movements to be categorised as such. In works including Revolution Without Revolutionaries and Life as Politics, Bayat argues that in autocratic regimes, public expressions of dissent are often less likely than in democratic liberal regimes, but this does not mean that citizens in authoritarian contexts do not engage in subversion of and challenges to the public social order. To understand the role of the urban poor we can examine the practice of street vending in general and people like the aforementioned Bouazizi in particular.

Street vending is illegal in many parts of Cairo, especially the more policed Westernised spaces such as near the offices of public officials, and yet the city is filled with street vendors, with or without licence, earning their economic livelihoods while engaging with the police force and public space. They claim their right to the city via ‘quiet encroachments.’ The vendors maintain passive networks among themselves by participating in this activity in large numbers together, confronting the state and its agents on the streets. Their solidarity is not born on the internet but through the nooks and corners of the streets where they communicate, participate in social life, express themselves politically and earn their living. The art of maintaining a presence in public space is an act of resistance in itself. In a society where open political expression is criminalised, these small acts carried out in large numbers become the forms of agency for local people. Not recognising these traditional and covert forms of encroachment and activism gives the impression that between the occasional episodes of insurrection society is static, which it is not.

Common acts of resistance, which often take place in the absence of technology, are coordinated spontaneously and gain strength in numbers. Mohamed Bouazizi, for example, was daily confronting the state by vending with an illegal license in a prohibited space, according to state authorities. The urban poor who are recent migrants from rural areas have become an important demographic in almost all Middle Eastern countries. Even spaces which are supposedly completely without ‘traditional’ activity, used to present a Westernised image for the media such as Cairo’s Tahrir Square, are dominated by this class. The urban poor have changed the landscape and spatial politics of Egypt and other countries in the region and the resistance by these subaltern groups cannot be captured by the dominant lens of Western academic social movement literature.

These informal groups are a breeding ground for ‘street politics’ and ‘forging identities, enhancing solidarities and extend their protest beyond the immediate circles to include strangers’ (Bayat, 2009, p.13). The strangers have shared grievances, experiences and channels of communication which can multiply the participants in contention episodes that take place in the streets despite no formal organisation. Such forms of collective action are also harder to repress, as they flow through corners, gullies, alleys and streets.

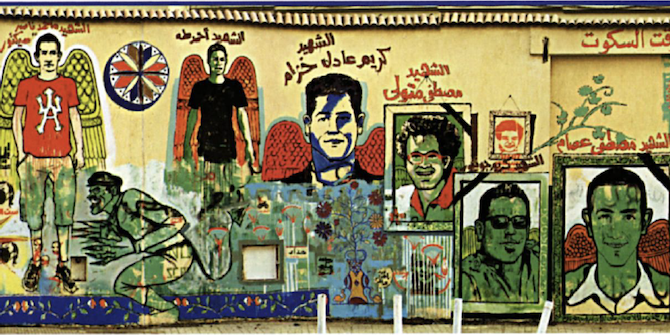

When talking about public space and asserting claims upon the streets, it is important to highlight the street art that emerged during and before the onset of revolution, the ‘Walls of Freedom’. Politically charged art is an expression of youthfulness, social change and a challenge to public authorities. It is a political act exercised in a regime where the cost of direct political participation is otherwise too high. Western academic literature focused on contention often neglects these innovative ways in which people in authoritarian regimes create spaces of resistance.

Theatre can be also categorised as part of this quiet encroachment upon public space, or acts of covert contention before the revolution. In the book, Tahrir Tales, Mohammad Albakry explains how street artists and theatres slipped past government censorship and created subtly political plays for audiences before the revolution. Playwrights wrote about government injustices against ordinary citizens but would use symbolism and historical settings in a way that would help them escape any direct confrontation with authorities. The plays would be performed in street theatres in rural and urban centres.

Graffiti is an attempt to openly occupy street walls and defy the state in multiple ways – challenging it through claiming public space and asserting the presence of youth identity. Even before 2011 politically charged graffiti and murals could be found throughout the city, but during the revolution there was a ‘surge of creative energy,’ with Aomar Boum calling this ‘festivalization of dissent’ (Boum, 2019). Mark LeVine claims that during that time, almost every wall in every street became filled with graphic and visual declarations of revolution and opposition to Mubarak, new murals emerging week by week. The art was ‘self-perpetuating’ and ‘each crackdown of the police produced more art’ as if the art was a sign of erasure of fear (LeVine, 2015, p.1282).

Taking ownership of public space in this manner is a challenge to the social power of the state. Egyptian Revolutionary artist, Ganzeer, calls graffiti ‘modes of social expression,’ commenting that ‘Egyptian artists really knew how to utilize the power of street-art’ and indeed the space of streets (Ganzeer.com).

Social media undoubtedly played a huge part in the revolution by linking large numbers of people to a common cause and reducing the political cost of action, however, this network would not have been able to sustain the movement without the acts of resistance that fed the protest momentum. This piece attempts to contribute to the debate about the spatial politics and urban rootedness of the Egyptian revolution. The role of social media was permissive, not deterministic. Through recognising the importance of spatial politics and embedded resistance in society, we ought to rethink the broad narrative surrounding the Egyptian revolution, rather than simply reducing it to the role of social media.