by Yunus Abakay

Following the death in a Tehran hospital of Jîna (Mahsa) Amini, a Kurdish woman tortured in detention for not wearing hijab appropriately, protests against the Islamic regime in Iran are entering their third month. The uprising began both in the capital and Jîna’s hometown Saqez, a Kurdish city in the western part of the country, igniting the eruption against the regime’s dos and don’ts framed by the slogan Jin, Jiyan, Azadî (Women, Life, Freedom). The protests spread across the country, building momentum and effectiveness as their gravity has drawn in people of different social strata in Iran and across the globe.

Although the ongoing protests brought people experiencing oppressive measures together against the regime, the intersectional nature of the struggle for marginalised communities is already at stake. The cultural appropriation of the Kurdish slogan Jin, Jiyan, Azadî to Persian – Zan, Zendegi, Azadi – (later, Persian protesters also added Man, Nation, Prosperity), distancing Jîna from her identity by excluding her Kurdish name from statements, barring Kurdish identity from protests organised by the Persian diaspora marching with the flag of the Shah’s regime, and limiting discussions to the Islamic nature of the regime has already masked the intersectional oppression that non-Persian ethnoreligious communities experience. In the possible scenario of a change in power in Iran, this poses the risk for minorities of one oppressive regime replacing another, as happened in 1979.

The regime’s body politics, with the imposition of hijab in public spaces as the marker of its power, is not the first of its kind that the country experienced. In 1928, inspired by neighbouring Turkey’s ‘hat law’ that had passed in 1925, the Shah’s regime passed a law regulating men’s head-covering by imposing a French army-style hat to mark the country’s modernisation. The genealogy of such a policy goes back a century earlier to the fez-hat mandate of the Ottomans that came into effect in 1827, also to signify the state’s modernisation. These policies also marked the state’s interest in nation-building by regulating bodies to create subjects as the carrier of its power and diffusing it to the micro-level of society.

Despite popular analyses that focus on the Islamic frame of governance in Iran, the state machinery in its modern structure, framed by the idea of a nation, is the basis of the regime’s power. The nuance lies in the difference between religious obligations binding the believers – and the God from whom the believers derive their identities – and a nation-state regulating the public sphere and managing a population of citizens who receive their identity from the state. The subjects and the public – rather than God, as the Islamic Republic would otherwise assert – also constitute the space from where the regime receives its identity and measures itself, demonstrated by its enduring interest in public appearance. This change from the idea of a community (ummah in the Islamic framing) to population management entailed social engineering projects that, throughout the 20th century, motivated various policies that precipitated genocides and programmes of cultural extinction, such as the death of indigenous languages across the world.

From a more comprehensive perspective, it can be observed that the Iranian state administers many more regulations similar to the imposition of hijab but with no religious motivation. The one-language policy that aims at standardising the population into a more homogenous nation reflecting the regime’s character is a major example. The denial of officially recognised languages other than Persian expressed in Jîna’s double identity – Jîna to her family and Mahsa to the state – is a case in point. Article 15 of the constitution imposes a one-language policy to ensure the sole dominance of Persian in public spaces, institutions, and services while defining other languages as tribal and regional. Article 16, which mandates teaching the Arabic language in secondary schools, justifies this due to it being the language of Islamic texts and permeating Persian literature, denoting the intersection of the Islamic and Persian characteristics of the regime. Under the Islamic regime, the Persian language is the sole means of accessing education and public services for other ethnic groups who are not native Persian speakers and constitute about 50 per cent of the population. Education in other languages is strictly prohibited, and activities questioning and challenging this exclusionary and oppressive policy are met with extreme repression from the regime.

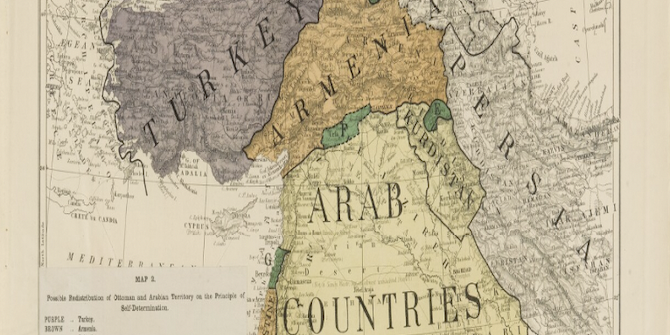

This marginalisation also reflects in the disproportionate disciplinary measures that minoritised communities whose regions are heavily securitised go through. A UK government report from September 2022 recorded that almost fifty per cent of all political prisoners in Iran are Kurds, who, as a community, constitute only 10 per cent of the population. The UN Human Rights Council report from 2021 documented the execution of 69 Kurdish prisoners and the use of the death penalty and disappearances as a means of deterrence against political activity from Kurdish, Arab, Baloch and other communities. The report also documents the arrest of activists for teaching their native languages and demanding the right to education in their mother tongues. Zara Mohammadi (pictured), recognised as one of the BBC’s 100 ‘inspiring and influential women from around the world’ for 2022, was sentenced to 5 years in prison for teaching Kurdish to children, while Abbas Lisani was sentenced to 15 years for demanding education in the Azeri language. Baha’i, Bakhtiari, Balochi, Turkmen and other ethnoreligious communities also experience similar disenfranchisement on the basis of posing a threat to the unity of the country, which institutionally excludes non-Persian identities. This view is also observable in the level of violence that the regime uses against protesters, with a far greater degree perpetuated against minoritised groups such as Baloch and Kurds.

Intersectionality, a concept developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw, works to analyse these overlapping forms of oppression, such as racism and sexism, in the body of a Black Woman and as negative characteristics in the institutions. It suggests that social justice requires recognition of the interacting forms of oppression together as expressed in Jîna’s body: carrying a Persian name (Mahsa) and wearing hijab in public while having a Kurdish name (Jîna) and not complying with hijab standards in private. Although expressed in the body of a Kurdish woman in this event, this is also the case for other non-Persian ethnic groups that constitute half of the population. The cultural appropriation of the Kurdish slogan Jin, Jiyan, Azadî to Persian and the negation of Jîna’s Kurdish identity from the protests have already masked the demands of those double oppressed. To establish a libertarian discourse from the ongoing mobilisation and to prevent replacing one oppressive rule with another, there is a need to recognise the intersecting nature of the oppressive rule in Iran. The Islamic frame through which the regime is mostly discussed at the international level airbrush the compound sufferings half of the population experiences and poses the risk of not recognising the convergence of oppression that may continue under a secular regime.