by Francis Owtram

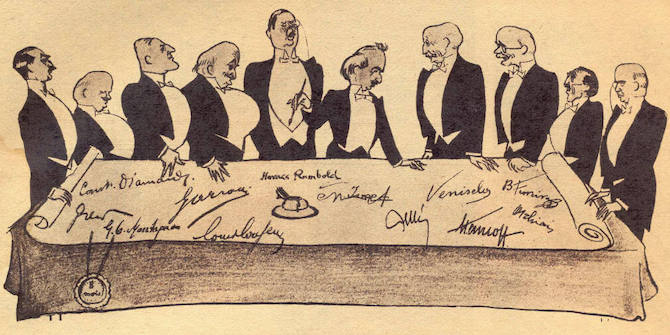

The Treaty of Lausanne (signed 23 July 1923) officially ended the war between the Allies (Britain, France, Greece, Italy, Japan, Romania and Yugoslavia) and Turkey [now known officially as Türkiye/the Republic of Türkiye].

It was the final treaty concluded at the end of the First World War and its outcomes remain in place to this day. The official title is the ‘Treaty of Peace with Turkey’, but it can be argued that by suppressing certain aspirations, particularly of the Kurds, it ushered in a century of conflict.

From Sèvres to Lausanne

For Turkey it marked a shift from the dictated peace of the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres – which would have reduced Turkey to a rump of territory in Anatolia – to a peace in which the Republic under its leader Mustapha Kemal Atatürk joined the club of nations as an equal sovereign state unencumbered by onerous Capitulations and humiliating legal stipulations on the treatment of foreigners.

The Armistice of Mudros, Lord Curzon and the Mosul Question

Signed at the end of the First World War, the Armistice of Mudros (30 October 1918) had ostensibly brought about a ceasefire between the British and Ottoman armies but the former raced forward to occupy Mosul on 14 November 1918.

This left the city and province of Mosul – and its purported vast oil wealth – in British hands. The Mosul question was born: should the Mosul vilayet be part of Turkey or the new country of Iraq? The inclusion of Mosul was a key point in the National Pact Project approved by the Turkish Parliament, which had also been approved in the final days of the Ottoman Parliament.

It was envisaged that this question could be resolved at the Lausanne conference. The head of the British delegation was the Foreign Secretary and former Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon. He was adamant about the importance of retaining Mosul under British influence and resisted Turkish attempts to settle the matter at the conference. Curzon requested a paper from J E Shuckburgh of the India Office on arguments against leaving Iraq, point 6 of which was: ‘By leaving the country we shall lose the chance of controlling the development of what may prove to be one of the great oil fields of the future. The advantage of retaining an oilfield under British influence is a matter on which the Admiralty will have something to say.’

Instead, the question of Mosul was handed over to the League of Nations, which, under a committee headed by a Belgian, ruled that Mosul should be part of the new British-controlled mandate of Iraq. In 1926, the Brussels Line was drawn as the boundary of Iraq, and Iraq agreed to pay Turkey 10 per cent royalties on Mosul’s oil resources for 25 years.

Curzon’s instinct turned out to be prescient as oil in vast quantities was discovered in Kirkuk in 1927, which turned out to be a source of conflict for the Kurds and Iraq for decades to come.

The Peoples Left Behind by the Treaty of Peace with Turkey

The delegates who convened from 1922-23 were notable for who was absent: Syrians and Palestinians attempted to attend but were excluded, while no Armenian, Persian [Iranian] or Kurdish delegation was invited. The British negotiator, Lord Curzon, did not even deign to meet the representative of the Sharif of Mecca, who had fought on Britain’s side in the war.

The Greeks of Smyrna: From Asia Minor to Nea Smyrni

Disaster had befallen the Greeks of Smyrna [Izmir]. Having thrown off Ottoman rule in the Greek War of Independence (1821), the Greek army had been encouraged by the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, to attempt to rewrite history and recapture lands in Asia Minor. Constantinople [Istanbul] was the capital of the Byzantine Empire before it was conquered by the Ottomans in 1453. Initially successful, the Greek forces were turned back by a Turkish military revived under Atatürk.

The Treaty of Lausanne accepted as a fait accompli that the Greek population of Smyrna was driven into the sea as the Turkish forces incinerated their homes, forcing them to rebuild in Athens in a district known as Nea Smyrni (New Smyrna). Under the terms of the Treaty, massive compulsory population exchanges on the basis of religion and ethnicity took place between Greece and Turkey.

The Armenians: War, genocide and suffering

Although the term genocide was not coined until 1944, the attempted extermination of the Armenian people, culture and society that took place between 1915–16 during the First World War is now widely accepted (outside of Turkish state narratives) as the Armenian genocide, when women and children were marched into the Syrian desert to die. This tragedy also created a vast number of Armenian and Assyrian refugees, but the Armenians were not to obtain a sovereign state until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Left Behind at Lausanne: The Kurds and their quest for an independent state

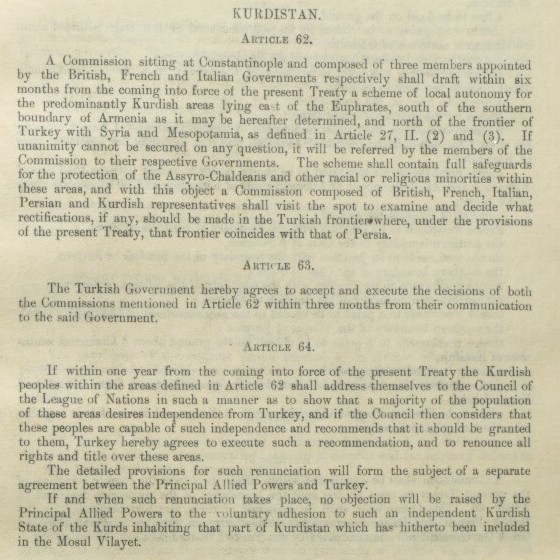

British imperial strategists considered the conference a success: they reasoned they had achieved the best they could in difficult circumstances. For the Kurds, however, Lausanne dashed their hopes. The difference between the articles of the defunct Treaty of Sèvres, which explicitly envisaged areas of Kurdish autonomy and an independent state, and the Treaty of Lausanne where any mention of a Kurdish homeland is completely absent, is marked.

For Turkey, Lausanne could be portrayed as the culmination of a victorious revival instigated by Atatürk, the Turkish hero of Gallipoli. However, for many of the peoples of the post-Ottoman space the consequences of the Treaty of Lausanne still resonate painfully a century later. For the Greeks it ended their irredentist dream of retaking Constantinople and made more than a million refugees. For the Palestinians it paved the way for the loss of their land; for Armenians and Assyrians it was no compensation for their experience of displacement and genocide. As for the Kurds it drove a stake through their aspirations for statehood and stored up conflict for the century to come.

Honorary Research Fellow, Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter

Further reading

Kristian Coates-Ulrichsen, The Middle East in the First World War (Hurst, 2014)

Jonathan Conlin and Ozan Ozavci (eds) They All Made Peace – What is Peace? The 1923 Lausanne Treaty and the New Imperial Order, (Ginko, 2023)

The Lausanne Project – the New Middle East, 1922-23

Francis Owtram, ‘Oil, the Kurds and the Drive for Independence: An Ace in the Hole or a Joker in the Pack’, in A. Danilovich (ed) Iraqi Kurdistan in Middle East Politics (Routledge, 2016)

Francis Owtram, ‘The State We’re In: Postcolonial sequestration and the Kurdish quest for independence since the First World War’, in Michael Gunter (ed) The Routledge Handbook on the Kurds (Routledge, 2018)

[To read more on this and everything Middle East, the LSE Middle East Centre Library is now open for browsing and borrowing for LSE students and staff. For more information, please visit the MEC Library page.]