This article is by LSE MSc student and Polis intern Pressiana Naydenova

Reforming the religion of Economics

Many of us do not question the current economic system because it requires effort to acquaint ourselves with the terminology behind which the biggest financial players hide their mistakes. Mistakes that often directly affect us. One of the more worrying elements of Eve Poole’s talk was the idea that the media is at the core of the chronic failure to understand and develop a critical approach towards Capitalism. While this may be doing a disservice to the many excellent financial correspondents and commentators out there, it was a provocative way for Poole to begin her talk, challenging some of the key assumptions of Capitalism.

The seven toxic assumptions of Capitalism

The seven toxic assumptions of Capitalism

Poole argues that since Christianity was the world view which created Capitalism, it makes sense to frame the debate within the same world view. The reference to religion is particularly apt given that Economists, very much like the Clerics, have been slow in challenging their own assumptions. The first flaw of Capitalism that Poole critiques, is the championing of ‘Competition’. She asserts that it does not make sense to be secretive and competitive above all else when effective business is about the building and maintaining of positive relationships. Positing competition as the preferred strategy also fails to take into account gender differences. Poole claims that a competitive environment is more suited to instinctual responses of men (“fight or flight”) than women who take a more collegiate approach when they “tend and befriend”. While the idea that competition should be replaced with cooperation is a noble one, linking certain behaviours to gender is in my opinion, somewhat reductive and contributes little to the discussion of Capitalism.

The invisible hand

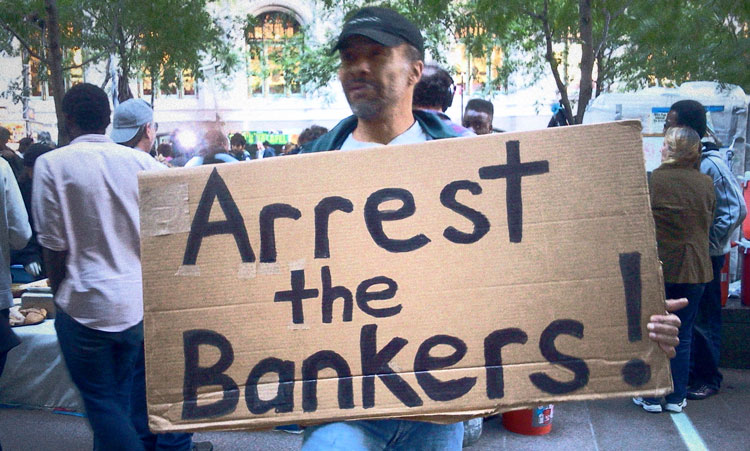

The second toxic assumption which Poole deconstructs is the “invisible hand”, the notion that governments should stand back from business and provide minimal market regulation because there is an invisible hand governing the flow of the market. While this assumption of self-regulating markets “cheers people up”, flocking behaviour of consumers does not always lead to a positive end. Following from this is the third toxic assumption, “utility”. Poole urges us to ask “utility for what?” and believes that a focus on utility creates a very transactional view of reality, which is ethically impoverished. Fourth, is “agency theory” which suggests that since we are all motivated by our individual interests, managerial interests will diverge from those of the shareholders. Poole suggests this pessimistic view creates an atmosphere lacking in trust where employers constantly need to design ways in which to keep employees in line, an environment that is ultimately toxic and unproductive in the long run.

Diamonds are forever

The fifth toxic assumption is that of “pricing” or the idea that the market price of goods is always the fairest price. Poole explains how prices are in fact manipulated, for example when businesses design campaigns to utilise children’s “pester power” to force parents into paying higher prices. Second-hand diamonds are worth next to nothing when compared with the price at which businesses sell new ones to customers, calling in to doubt the marketing claim that “diamonds are forever”.

Believing in Santa Clause

The sixth toxic assumption is that of ”shareholder value”, which Poole suggested is laughable considering that the majority of shareholders in the modern age are in fact computers and the average time a share is held is 11 seconds. The invisible “shareholder”, Poole suggests, has become a little bit like “Santa Clause” as businesses use him to justify their decisions and Poole argues convincingly that there needs to be more transparency about how mechanised the process really is. The seventh assumption is connected to the sixth and is the concept of “limited liability” meaning that as an investor you can lose only the value of the share you hold, when a business goes bust. Poole quotes that currently, 98% of companies in the UK follow the limited liability model, which she declares is a “monopoly of this type of company structure” which is not healthy for the system as a whole, as it provides no room for alternatives.

What can we do?

Poole concluded with suggestions for what each of us can do to reform capitalism into a more ethical and just system, particularly calling on journalists to provide more coverage of alternative business models and inform themselves better about the economic agenda. She proposed that on an individual level we could ask ourselves four basic questions:

1. Who do we bank with? Do we consider them an ethical bank or building society?

2. Where do we shop? Consumer boycotts do work.

3. Do we give to charity? If we sponsor local businesses it is better for our community overall.

4. Are we using cash? Paying with cash rather than a debit card can help struggling businesses.

We were left with the assertion that creating a more ethical Capitalism ultimately depends on all of us and the financial choices we make.

This article is by LSE MSc student and Polis intern Pressiana Naydenova

Polis hosts a series of Lunchtime Talks featuring media practitioners on Wednesdays 13.00-14.00 to discuss their roles and experiences of the sector. Open to staff, students and the public.

Polis hosts a series of Lunchtime Talks featuring media practitioners on Wednesdays 13.00-14.00 to discuss their roles and experiences of the sector. Open to staff, students and the public.

Thank you, Pressiana, for this very balanced review of my talk. I would be really interested in your ideas about what more the media – and all of us – could do to try to speed up reform. Any thoughts?

Eve, thank you for the kind words. I think in order to achieve meaningful economic reforms, we first need to convince a sizeable amount of people that change is necessary. A good way to do this is by raising awareness about issues (something which you are already doing) and by providing accessible and functional alternatives. Perhaps it would also be a good idea to ensure that there is better financial education provided in schools, because currently there seems to be a huge gap between those who do and those who do not understand the structure of the current system. Lastly, I think the division between individuals and the media is not as clear cut as it used to be, as more and more citizens become actively engaged in the media production process (e.g, bloggers) and the political impact of social media grows. In a sense we are the media and we are part of the economic system and thus by reforming ourselves we can make a positive difference. So, the short answer to a complex question is : I think the sooner we change our own behaviour and the more people do it, the quicker wide reaching reform will be.

There are several problems with the above. First and foremost, a more ethical world is the goal, but who’s going to decide what is “more ethical”? If somebody says they believe the capitalist world is more ethical than others because of its spectacular advances in all development indicators, who will establish that something else need be improved instead?

Likewise for prices, or share values…who will decide what’s fair and why?

there’s also a contradiction. Prices and all sorts of values are already determined by the decisions of individuals…why say those are not good choices only to conclude everything is up to those same individuals?

Thank you for your input, Maurizio, you have correctly identified that there are many questions that have been left unanswered. Mostly, this is because they are part of an ongoing debate into ethics and the Capitalist system and their answers can vary depending on whom you ask.

Regarding your point:

“Prices and all sorts of values are already determined by the decisions of individuals…why say those are not good choices only to conclude everything is up to those same individuals?”

I am afraid there has been a misunderstanding; I did not say that improving the system should depend solely on the same individuals, who are the top decision makers in companies/ the finance world/politics. I also did not say that the choices of all top decision makers are necessarily bad. What I did say is that our current system allows for “some” individuals to make important choices about how the system is run, without being subjected to the scrutiny of their customers. Actually, most of the time, ordinary people have no access to the decision making process at all and there is often not sufficient information provided about the transparency of price calculation and how the shareholding process really works.

This is why my primary goal was to highlight that there is a knowledge gap between ordinary people and finance specialists and that it should be bridged through education in order to be able to have more fruitful and representative discussions about how to make the system fairer. I also wanted to convey Eve Poole’s argument that, on an individual level, we have far more control over the ethical values that we choose to apply to how we spend. I think this is important because, it would allow me to answer your question “who will decide what’s fair and why?”. If, on a micro level, each of us makes decisions on what is fair, on a macro level more transparency would mean that consumers can either choose to buy or boycott goods/financial services they believe are unethical. This makes consumers the ultimate driving force behind what is accepted as ethical behaviour in business and what is not, rather than a small elite consisting of finance professionals.

Brilliantly put, Pressiana. And thanks for the challenge Maurizio. Without sidestepping your question about whose morality, I am still worried about a prior question: whose market? As well as individually responsible consumer, employer, investor behaviour, etc., I am keen that we open up market participation to as many global citizens as we can. At the moment it is colonised by the strong, and we create it in our own image. The more we can use our strength to enable the participation of others, the more we can use the powerful mechanism of trade to enrich more communities around the world. Of course we are still left with your brilliant dilemma – who should ‘control’ market outcomes such that they are ‘ethical’ – but at least we would then be starting from a more defensible place.