Have news organisations done a good job of covering COVID-19? As research from the Reuters Institute at Oxford shows, there are those who believe that journalists aren’t holding government to account effectively enough, others who believe that they aren’t giving government a chance, and some who believe that they are making the best of a bad situation. A discussion hosted by the LSE this week tackled the question of how well the UK news media has kept the public informed and held the authorities to account during the current crisis. Emma Goodman reports.

COVID-19 has been perhaps the hardest story that many journalists have ever had to cover, as Polis director Charlie Beckett noted in his introduction to the session. It is a huge, complex, fast-moving story and journalists have largely left their newsrooms and studios to work remotely. It is also, of course, one of the most important, with significant health and economic implications for most people in many countries around the world. And at a time when online misinformation is a credible threat, reliable, trustworthy news has a more crucial role to play than ever.

Despite levels of trust in news organisations reportedly falling, the public has been consuming a great deal of news content during this crisis. Many outlets have seen their audiences soar in recent months, as the public seeks information to understand not just what is going on around them, but also to directly guide decisions they are making in their own lives.

The Guardian’s readership in March and April was record-breaking, presenter of the Guardian’s daily news podcast Anushka Asthana told the panel, with numbers far exceeding those during key Brexit moments or Trump’s election. Podcast numbers are very high, with a large proportion of younger listeners: people are listening to in-depth reporting and there is a huge thirst for journalism.

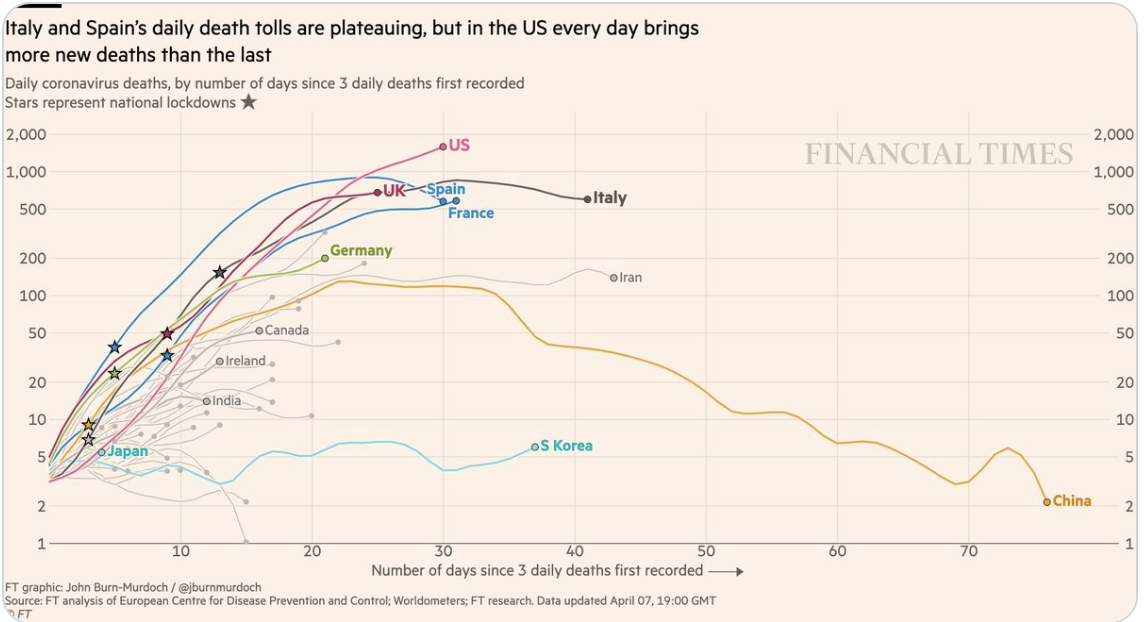

And despite the complexity of the story, the panel agreed that journalists have done some fantastic reporting and made worthy efforts to hold government and scientists accountable. Coverage of the dire situation in UK care homes has led to changes in policy, noted Annette Dittert, London bureau chief of German broadcaster ARD. Asthana highlighted the dramatic, powerful packages coming out of hospitals, which she says has changed the way that the public thinks about the NHS. Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, praised the way that, at a time when we have been overwhelmed by graphs and charts which risk de-humanising the pandemic, journalists have managed to ‘rehumanise’ the crisis. He also praised radio station LBC for the way that it has both provided a valuable critique while connecting the public to politics and policy.

Damaging Negativity?

Of course, news coverage hasn’t been perfect. Craig Oliver, communications consultant and former No.10 adviser, believes that the “factory setting of negativity” has damaged news reporting and the industry’s relationship with the public. Horton suggested that journalists should have taken the story more seriously earlier on, pointing out that the WHO declared coronavirus a global emergency on 31 January, although as Ashtana said, it was hard to break away from the government’s reassurance that they were ‘following the science’ and there was no need to panic.

Dittert said that she found clearer guidance on the crisis from the German media than the British media, although she stressed that this wasn’t to do with the quality of the reporting, but rather the situation the British journalists were facing, which involved investing a lot of energy into seeking to understand a government that was putting out incomprehensible slogans. “The German media had a much easier task here,” she said. The daily press conferences were “extremely unsatisfactory,” she added, stressing the lack of follow up questions as particularly problematic.

The panel discussed various challenges that journalists face in covering this vast topic:

+ The speed at which the science shifts and different concerns come to light is hard to keep up with, along with results of clinical trials being published first by press release rather than in academic papers.There is a lack of expertise among political journalists on science and health issues. Richard Horton called for specialist science journalists to be given more prominent roles in questioning politicians, and to be more empowered by their editors.

+ The need to define their role in this national crisis and balancing priorities: Daily Mirror political editor Pippa Crerar explained that her paper was trying to combine supporting the NHS with boosting morale, while holding the government to account.Working from home: on top of the practical considerations faced by all home workers, for audiovisual journalists this might include attempting to construct something resembling a studio in a bedroom using duvets and blankets.

+ For the Westminster-based lobby journalists, the lack of chance encounters, gossip and the chance to observe the body language of those you are reporting on can make finding stories more difficult.

+ An additional difficulty at the height of the crisis was that parliament was on recess for almost four weeks from late March, Crerar highlighted, meaning that there were fewer opportunities for scrutiny.

The Story Continues

The greatest challenges may be yet to come, however, as despite news outlets’ record-breaking audiences, the economic downturn and subsequent collapse of the advertising market means that the extra attention is not turning into extra income. Several larger news publishers have attracted significant numbers of additional subscribers during the crisis but these are not necessarily enough to compensate for the loss in advertising. The BBC is cutting 520 jobs, The Guardian up to 180, including 70 in editorial. Over in the US, an already bleak situation for local news is swiftly getting worse.

This is bad news for the public, whose need for reliable information is intensified by their lack of faith in the government’s communication. The Reuters Institute research has found growing concern among the UK public about misinformation from the government, Ofcom has found growing levels of confusion about how to respond to the crisis, and research at Cardiff University has found that people want to see more fact-checking of misleading government statements. A shrinking Fourth Estate is only going to exacerbate these problems.

This article by Emma Goodman, a policy officer in the Department of Media and Communications, LSE

Click on the image below to watch a recording of the whole debate: