“The situation is nowhere near as dire as what is commonly portrayed in the popular press”, writes Dr Guanie Lim, Research Fellow at the Nanyang Centre for Public Administration, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

_______________________________________________

Is China buying up Southeast Asia? This is the million dollar question facing our generation and it is worthwhile to devote some attention into unpacking it. To this end, I examine Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) entering Southeast Asia along two dimensions: quantity and quality.

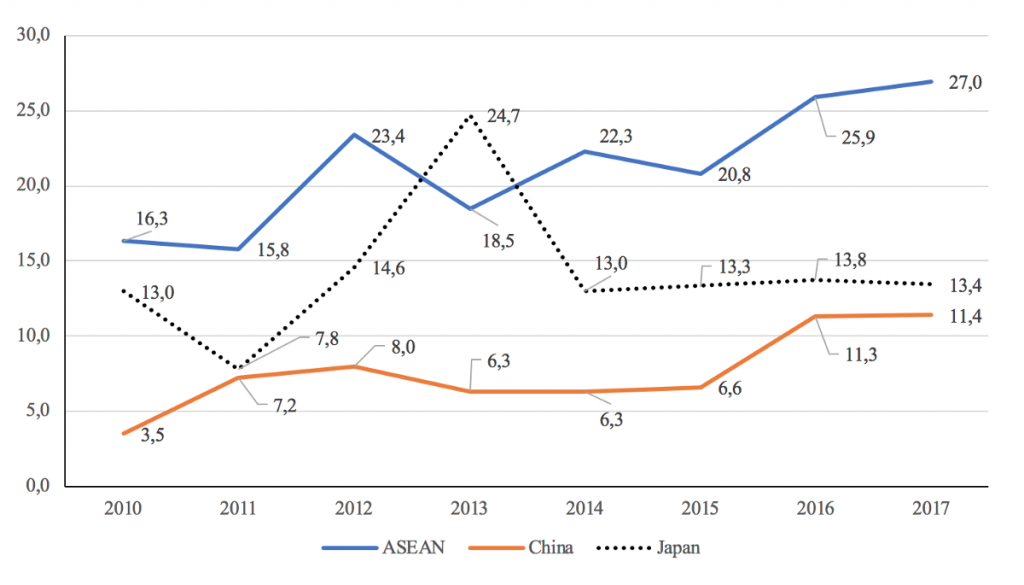

Firstly, the quantity of Chinese FDI is not as ‘big’ as what is commonly mentioned in the popular press. In terms of flow of FDI, Figure 1 shows that Chinese transnational corporations (TNCs) have not out-invested ASEAN and Japanese investors, the two traditional players in the region. Although Chinese FDI has increased between 2010 and 2017, its rate of increase has not outmatched those of ASEAN and Japan.

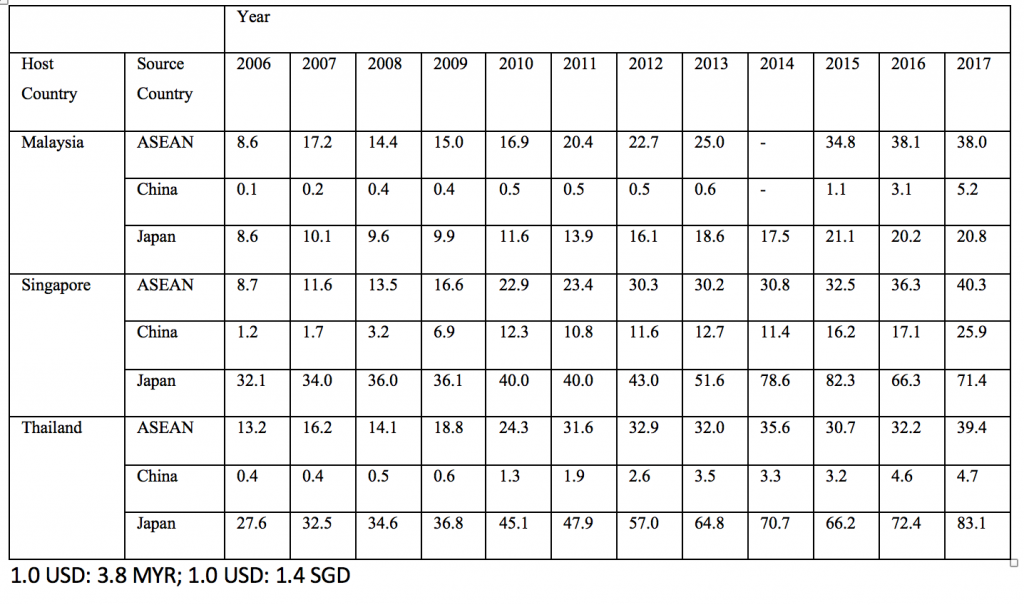

The stock of FDI tells a similar story (see Table 1). In three of the more mature Southeast Asian economies (i.e. Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand), Chinese FDI clearly is behind ASEAN and Japanese FDI. In Thailand, Southeast Asia’s manufacturing hub, the gulf between the stock of Chinese FDI and Japanese FDI is almost 20-fold.

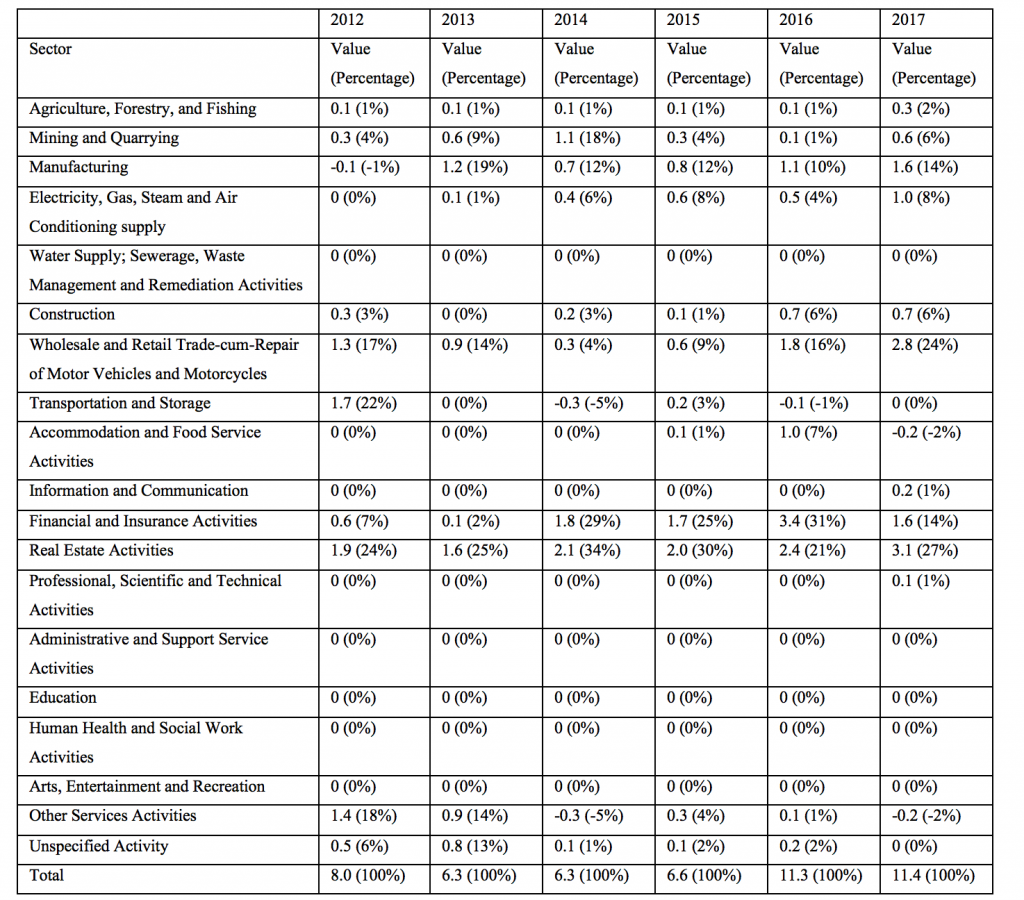

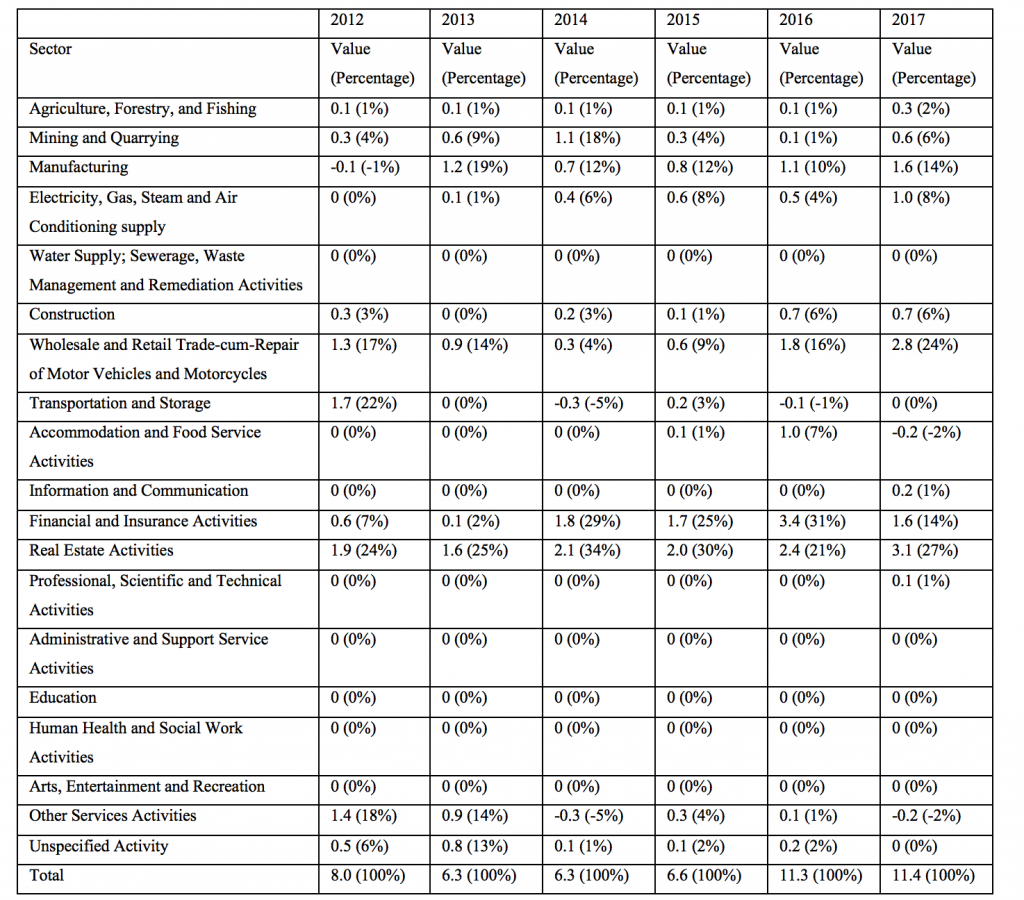

Secondly, analysing the qualitative dimension of FDI entering Southeast Asia, one discerns the lack of traction of Chinese FDI vis-à-vis FDI from ASEAN and Japan. Tables 2, 3, and 4 show the contrast in composition of the flow of Chinese, ASEAN, and Japanese FDI from 2012 to 2017. For China, its TNCs have mainly invested into the tertiary sector, led by real estate activities, financial and insurance activities, and wholesale and retail trade-cum-repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles. As much as 40% to 68% of Chinese outward FDI into ASEAN has gone into these three activities during the period observed. Out of these three activities, real estate development is the most heavily represented, accounting for 21% to 34% of total Chinese outward FDI. It is widely believed that much of the Chinese FDI classified as real estate development entering ASEAN has gone into luxury projects that contain rather speculative elements, with little direct benefit to the local population. Contrarily, manufacturing-related FDI is relatively meagre in value, representing only an average of 11% of Chinese outward capital into ASEAN.

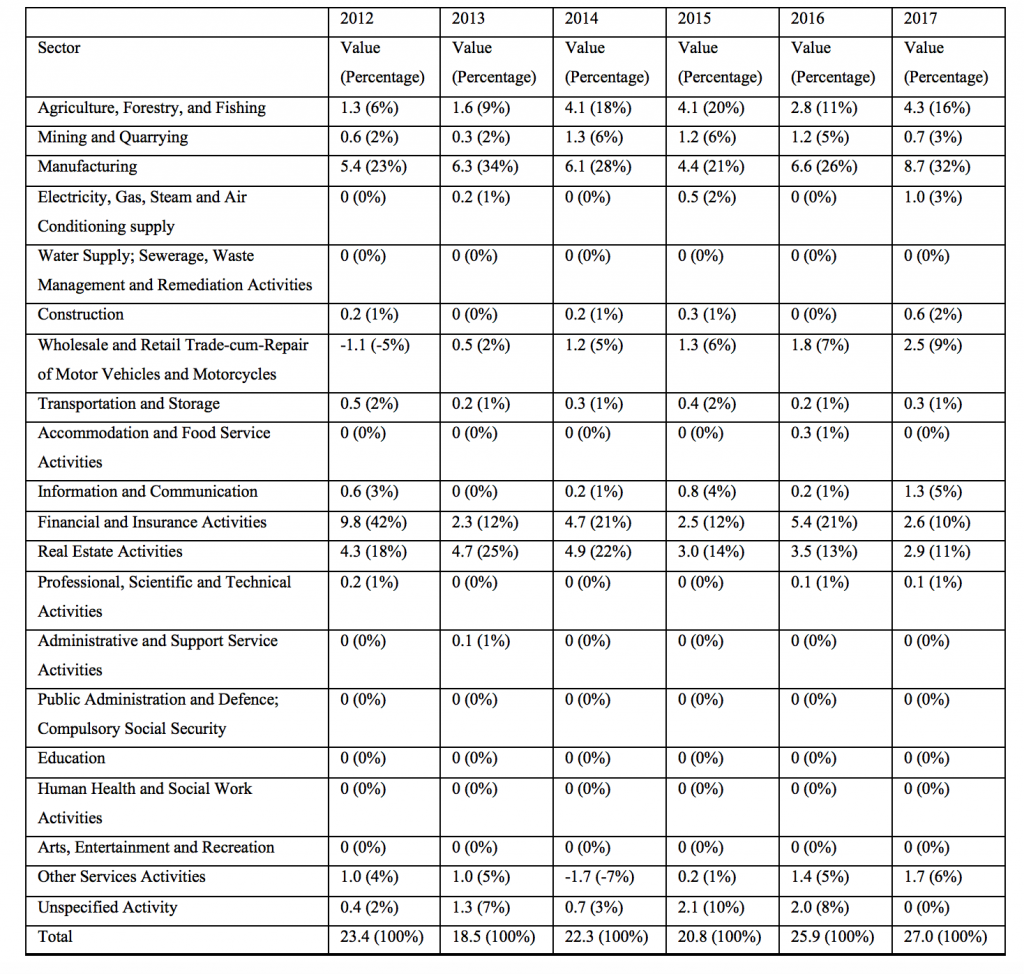

For ASEAN, close to one-third of its FDI has financed manufacturing activities from 2012 to 2017. The second most important activity financed by ASEAN TNCs is financial and insurance activities, contributing an average of 20% of ASEAN FDI — despite some fluctuation in value — during the period observed. ASEAN TNCs’ third most favourite activity is real estate activities, accounting for an average of 17% of their FDI during the period observed. Unlike Chinese and ASEAN FDI, a very high percentage of Japanese capital has gone towards manufacturing activities. Apart from 2012, 35% to 55% of Japanese FDI has financed manufacturing in ASEAN. The heavy presence of Japanese FDI in manufacturing reflects the resilience of Japan TNCs-orchestrated production networks and industrial organization. More importantly, Japanese manufacturers remain powerhouses in the region’s critical industries such as automobile and tools and machinery, pressing home the goodwill and brand name they built when they established production facilities in Southeast Asia en masse following the 1985 Plaza Accord which led to the rapid rise in the value of Japanese Yen (JPY), otherwise known as endaka (literally translates to ‘expensive Yen’).

More broadly, how does the spectre of a supposedly globalizing China mesh with the ongoing tension between US and China? Figure 2 shows that the situation is nowhere near as dire as what is commonly portrayed in the popular press. Except for 2018, US investors have consistently out-invested Chinese TNCs, enjoying a considerable margin. Like TNCs from EU-28, ASEAN, and Japan, US investors have invested into the region several decades before the Chinese. This in turn grants them early-mover advantage in establishing corporate activities in ASEAN. Likewise, courtesy of their latecomer status, Chinese firms lack experience investing and conducting businesses overseas.

A paranoia-fuelled viewpoint on Chinese FDI is unproductive as it indirectly heightens Beijing’s geopolitical agenda (whether substantiated or not), simultaneously pressuring Southeast Asian policymakers into thinking that they need to appease China in order to acquire Chinese money. Western and Japanese policymakers, in turn, refocus their energies toward warning countries about Chinese money rather than providing viable alternatives such as increasing their own economic presence in the region. This narrative has to stop as what matters more — now and going forward — is to view things for what they are. That is, Chinese FDI entering the region has indeed grown, but not necessarily more so than that of all the other major economies.

References:

Lim, G. (2019). China’s Investment in ASEAN: Paradigm Shift or Hot Air? GRIPS Discussion Papers, 19(4): 1–17.

Lim, G. (2017). China’s ‘Going Out’ Strategy in Southeast Asia: Case Studies of the Automobile and Electronics Sectors. China: An International Journal, 15(4): 157–178

Liu, H. and Lim, G. (Corresponding Author) (2019). The Political Economy of a Rising China in Southeast Asia: Malaysia’s Response to the Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of Contemporary China, 28(116): 216–231.

*This blog is based on Dr Lim’s talk delivered at the 2019 LSE Southeast Asia Forum.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

* Banner image is from Hunan Provincial People’s Government (2016).